Part 1: Navigation, Dredging, Channel Changes and Jurisdiction, and Part 2: Sewers and Sewage Treatment

This page, first published on PhillyH2o about 2005, now has additional photographs and maps at much higher resolution than the original post.

Sources used include the following:

- Evening Bulletin Newspaper Collection at the Temple University Libraries Special Collections Research Center

- Chronology of Sewage Disposal Activities, City of Philadelphia (No author, no date. Typescript, 71 pages. Original in PWD Archives) Provides a detailed view of Philadelphia’s sewage disposal project in the period 1905 to 1943. (Hereafter referred to as “1943 Chronology)

- Report on Flood Control, Frankford Creek, City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Knappen Engineering Company, 280 Madison Avenue, New York 16, N.Y. October 1947. An invaluable report that gives both the history of developments along the creek and the plans that were used in the concrete channelization and diversion project undertaken from 1948-1956.

See also companions to this document, “Frankford Creek Watershed in the Context of the Development of Philadelphia’s Sewer and Sewage Treatment System,” and “Frankford Creek Watershed: A historical overview of the Philadelphia section,” in which the events in the following timeline are discussed in a more narrative form. Although the information for all three pages is similar, each features different images so they are all worth checking out.

INTRODUCTION

The Frankford Creek begins at the confluence of the Tacony (also called Tookany) Creek and Wingohocking watershed includes the tributary watersheds of Tacony Creek and Wingohocking Creek. Rock Run was a major tributary of the Tacony, and Little Tacony Creek (also called Tackawanna Run) flowed into the Frankford. Along with the Wingohocking, these and other minor tributaries within Philadelphia have all been diverted into combined sewers. Though these tributary streams no longer flow on the surface, their original watersheds still exist as “sewersheds,” and are the source of much of the storm drainage that reaches the surface streams, and also of combined sewer overflows.

PART 1: Navigation, Dredging, Channel Changes and Jurisdiction, 1799-1956

In 1799, the Pennsylvania Legislature declared Frankford Creek a navigable public highway “from the mouth up to Joseph L. Miller’s land, opposite the race-bridge across the Bristol road, on Main Street [now Frankford Avenue], in Frankford.” This meant that all bridges built across this stretch of the creek had to be moveable, to allow the passage of small barges and schooners. Negotiating the twists and probably difficult, because of the winding, shallow channel.

In 1836, “Philadelphians then called [the highway through Frankford] ‘the street of beautiful vistas.’ It is narrated that Frankford Creek was still a stream of sparkling water, rippling over a pebbly course, and filled with fish.” (Source: Bulletin editorial, 1920s, Temple University Libraries Urban Archives, Folder 81: “Frankford History”, page 4) This was likely an idealization of the creek’s water quality, especially below the confluence with the Wingohocking. According to the 1849 Dripps Map, which covers only part of the Frankford Creek watershed, there were more than 30 mills and factories located along the main and tributary creeks. Most manufactured some form of textiles, but others made products including chemicals, tools, flour, and umbrella sticks.

After 1884, the U.S. Government did nothing to help the City maintain a navigable channel in Frankford Creek. It refused to help in 1910, 1934 and in 1938, citing the lack of prospective commerce. (Click here for an overview of previous investigations into the creek from 1947 Knappen Report.)

1888: Juniata Park, created from the estate of Comegys Paul, was placed on city plan by ordinance of July 2, 1888 (later amended April 11, 1890). Original park was 30.1 acres, bounded by Frankford Creek and Cayuga, L, and I streets. (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1892, p. 39)

While other changes in the channel of the creek were made in the 19th century, the 1901 alteration was the first of which there is a definitive record. That year the course of the creek was changed between Kensington Avenue and Frankford Avenue. “This work, when completed, will accomplish an urgently needed improvement, rectifying the devious lines of Frankford Avenue as fixed by the old course of Frankford Creek, [and] reduc[ing] the liability of inundation of the adjacent streets and property by the increased capacity and more direct course of the new channel.”(SOURCE: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1901, pages 108-111. Click here for an overview of previous projects for improvement along the creek from the 1947 Knappen Report.)

In 1908, Tacony Creek Park was confirmed on the city plan. The parklands were not improved until the mid-1920s, when an intercepting sewer was built through the territory. (Source: Bureau of Surveys)

From 1915 to 1929, the City tried to maintain the channel, and upwards of $2,500,000 were said to have been expended for dredging and other work in that period. For example, on February 28, 1916, the Bulletin reported that the dredging of 40,000 yards of material from Frankford Creek above Bridge Street was to be done by American Dredging Company. The mouth of the creek, where the depth of water was only 3.5 feet, was also to be dredged to make the creek navigable. A March 27, 1923 article in the North American reported: “Representatives of property owners and industrial concerns bordering on Frankford Creek yesterday urged city officials to consider the advisability of straightening the horseshoe bend in the creek to permit of easier navigation by barges….[City officials] told the delegation that while the plan of improving the creek is feasible, there are no funds. The improvement would cost $250,000.”

Navigation in the creek ceased in 1929, due to constrictions in the channel caused by silting from, among other reasons, upstream erosion, the removal of dams and the resulting release of ponded up silt, and deposition of solids from sewage and industrial wastes.

Throughout the 1930s, floods ravaged the watershed, especially in Frankford Creek below Juniata Park, and in the Logan neighborhood in the former Wingohocking watershed. On August 18, 1932, “flood waters of Frankford Creek cut a channel through land of American Pile Fabric Co. north of dam and west of Wingohocking Street.” In a flood on July 2 and 3, 1933, “fifteen feet of the dam across Frankford Creek west of Wingohocking Street failed. The entire dam was later torn down and not rebuilt.” (Source: 1943 Chronology) An August 6, 1932 Bulletin editorial summed up the problem neatly: “What happens after every extraordinary rain storm is not wholly a visitation of Providence. The flooding is one of those forseeable phenomena the costly consequences of which would have been prevented.” (Click here for an overview of the history of flooding on Frankford Creek from the 1947 Report.)

In 1934, the horseshoe bend between Margaret and Bridge streets was removed and a new channel dug for the creek by a crew of more than 1,000 men. (Source: Bulletin, March 22, 1934)

In 1938, “at a public hearing held by the War Department in Philadelphia, private interests along the creek indicated a desire to have the federal government again improve the lower reaches of the creek for navigation. Further inquiry revealed that the type of vessel that would now use the channel would draw 12 feet of water and would require a channel depth of 15 feet. The initial cost of such an improvement would have been prohibitive.” In a newspaper report about that meeting, a local congressman called the creek “the lost child on the chart of the Delaware River.”

In 1940 and 1941, the Federal Government and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania passed acts declaring the creek to be non-navigable, finally giving the City of Philadelphia sole jurisdiction over improvements and changes in the creek.

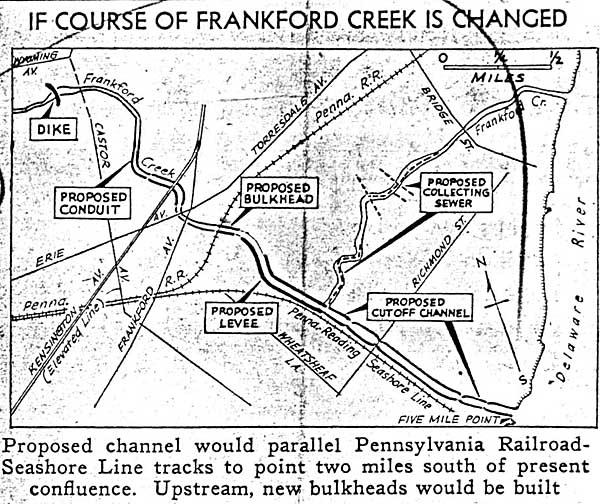

In 1947, Knappen Engineering Co. of New York City was hired by the City to develop a comprehensive flood control plan for Frankford Creek. A newspaper article about the plan features a drawing of the creek, with the caption, “A snake that will be straightened out.” The first part of the plan to be completed, in 1949, was the removal of the horseshoe bend in Juniata Park. (SOURCE: Bulletin, May 8, 1949, and other newspaper articles.)

In 1956, one of the final pieces of the Knappen flood control plan was completed, when, on October 17, the new diversion channel was opened that carried the creek directly to Delaware River, avoiding the long loop through Bridesburg and past the Frankford Arsenal.

PART 2: Sewers and Sewage Treatment: Pollution, Plans and Delays

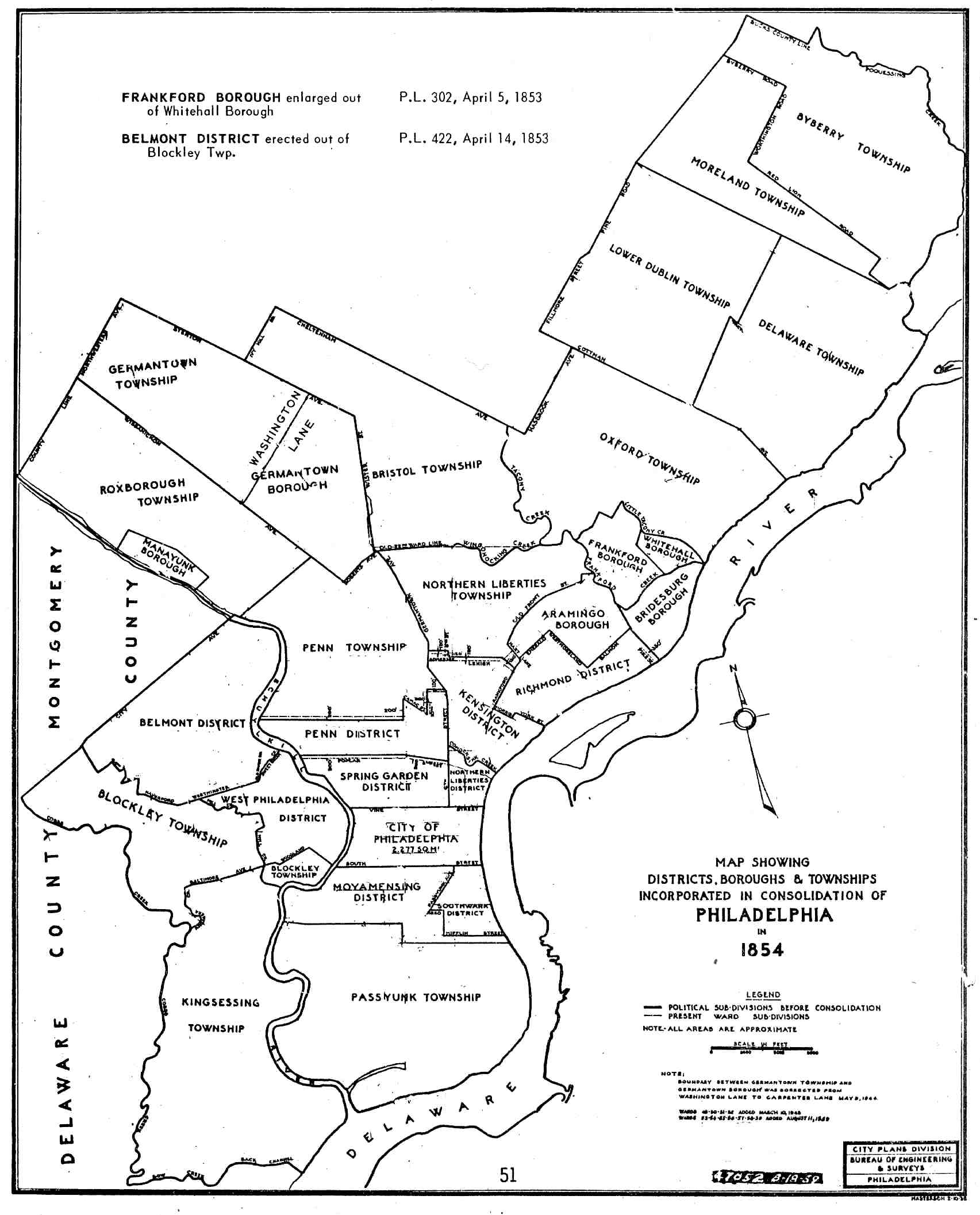

1854: Under the Act of Consolidation, City of Philadelphia absorbed all the municipalities in Philadelphia County, expanding from 2 square miles to more than 129 square miles. This area included the 22 square miles of Tacony-Frankford watershed within Philadelphia County. (About 15 square miles of the watershed are in Montgomery County). Only 35 miles of sewers existed at the time in the entire city.

1888: City engineers made a preliminary study of Tacony and Frankford Creek drainage areas. At this early date, officials were already projecting that the City would have to deal with sewage flow from Montgomery County, “to prevent the channel of Tacony creek from becoming a future nuisance.” (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1888, pages 119-121.)

1889: A petition for the extension of the Wingohocking Sewer, signed by notable citizens and medical professionals of Germantown, was presented to the Mayor and City Councils. At that time, roughly a half-mile of the creek ran in an underground conduit northwest of Penn Street. Ten miles of branch sewers in Germantown drained into the creek, making the open section of creek southwest of Penn Street a dangerous open sewer that threatened both health and property. Unlike many other sewer projects, which took years to get the necessary funding from City Councils, this one (no doubt due to its influential supporters) was begun the following year, with 3,400 feet of main sewer built at a cost of $70,000. (Sources: Petition for the extension of the main sewer on Wingohocking Creek from Penn Street to Fisher’s Lane, 22d Ward; Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1890, p. 161.)

1895-1901: In 1895 City engineers advocated an interceptor system to alleviate pollution of Frankford and Little Tacony Creeks. The goal at that time was to divert excessive storm flow directly to the Delaware River, and build an interceptor to pick up the sewage before it entered the creeks. Year after year, no money was appropriated by City Councils for this work, and each year in his reports the City’s Chief Engineer and Surveyor grew more and more exasperated. A series of newspaper articles in 1899 highlighted “the increasing unsanitary condition of Frankford and Little Tacony Creeks, by reason of the extension of branch sewers in Frankford” that emptied their sewage into these creeks; and while the public was promised some solution, no work was yet undertaken. In 1901 the Chief Engineer wrote, “The condition of Little Tacony Creek is growing yearly more unbearable…. A great number of sewers have been built in the past two years draining a densely populated section and discharging…into [the creek]…. A relief from these conditions is urgent, and it is undoubtedly a better policy to carry on the work by making annual appropriations of moderate amounts than to delay the beginning of the improvement for some time, when the necessity will have become so great as to require an appropriation of very large amounts in order to accomplish speedy relief from the unsanitary conditions which exist.” Work on the project finally began that year when a small section of Little Tacony Creek was buried under a new street, Pratt Street. (Sources: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1895, p. 82; 1899 Report, p. 73; 1901 Report, pages 74 and 80, and accompanying plan of Pratt Street Sewer.)

1896: Extension of the Wingohocking Sewer to Mt. Airy is deemed “urgent, owing to the fact that the whole of Mt. Airy, comprising hundreds of suburban homes, with many miles of paved streets, has no sewerage and must be deprived of any efficient drainage until the sewer is extended to reach this section.” (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1896, p. 79)

1904: Construction began on Rock Run sewer system. Work on this sewer continued into the 1920s until the creek was finally completely underground. Construction continued on Wingohocking Creek sewer system, as it had almost yearly since 1890. Construction continued on the Little Tacony Creek system. “The project is to practically abolish Little Tacony Creek by intercepting the whole flow to the northward of town and carry[ing] it through the divide into Frankford Creek near its mouth.” Torresdale Avenue was one of the streets that were eventually built over the creek bed. (Sources: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1904, pages 85, 76-78, and 80)

1905: Work continues on Wingohocking Creek sewer system. “This system is so large, comprising in addition to the main stem, three main branches, each of the dimensions of the larger main sewers, that scarcely a year passes that something is not done upon the extension of one of the other of them. Extensions are required to meet the demands of building improvements. One stem recently completed through Mt. Airy has served to open for developing a tract of more than 300 acres.” (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1905, p. 58)

1905: On April 22, the Pennsylvania legislature passed Public Law 260, also called the Clean Streams Law, “to preserve the purity of waters of the State for the protection of the public health.” Among many other provisions, this law required the City to get the approval of the state Department of Health (and in years to come, the Sanitary Water Board) for all new sewers and sewer extensions. The goal of the law was to rid the state’s waters of sewage pollution, but accomplishing that goal took more than half a century.

1906: Typhoid Fever and Water Treatment —The annual typhoid fever epidemic killed 1,063 Philadelphia residents. The disease is mainly caused by the consumption of drinking water contaminated with raw sewage. Typhoid deaths finally began to diminish once water filtration plants were in place for the entire City. After chlorine was added to the filtered water, beginning in 1913, typhoid cases quickly fell to negligible levels. As most large cities at the time, Philadelphia saw that it was a simpler and less costly public health measure to treat the drinking water supplies than it would have been to collect and decontaminate the City’s sewage. That step took another 50 years to accomplish.

1907: Frankford Creek Culvert Proposed – A State Department of Health permit for extension of sewers in Frankford Creek drainage district included this note: “In connection with the plan for the Frankford Creek Intercepting Sewer, the creek is to be improved and possibly arched over and a broad avenue constructed over it.” The “improvement” of completely covering the creek, of course, was never done, except in one small section. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1908: “The purification of Frankford Creek is one of the most important public projects that can be undertaken, affecting as it does a population of 30,000 people resident in the Frankford section of the city.” Contributing to the pollution of the creek was the Wingohocking system, by which the sewage of 60,000 people was carried into the creek. (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1908, p. 61)

1909: Millions of gallons of sewage pouring into Frankford Creek from Germantown via Wingohocking Creek “may make it essential that one of the first projects in the purification of sewage be carried out in the Wingohocking territory.” The Northeast Sewage Treatment Works, completed in 1923, was designed to serve exactly that need. (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1909, p. 59)

1913: Water filtration, combined with chlorination of drinking water supplies beginning in 1913, greatly reduces typhoid cases, and lessens the immediate need for sewage treatment. (See also note under 1906.)

1915 Report on the Collection and Treatment of the Sewage of the City of Philadelphia, a 188-page report, was published and submitted to the State Department of Health for approval, as called for under the 1905 Clean Streams Law (see note above). The plan called for the expenditure of “$5 million annually for the next five years for the construction of the necessary works.” It outlined a series of collector/interceptor sewers that would keep waste out of City water streams and carry it to three sewage treatment works along the Delaware, for purification. The state approved the plan in 1915. (Click here to view this report and two preliminary reports)

1915-1916: Sewage Disposal Project Bureau of Surveys annual report recommends, among other appropriations, $1 million for the completion of the Frankford Creek system of collectors and the beginning of the Northeast Sewage Treatment Works. The following year, plans were approved and contracts were awarded for various portions of the Frankford Creek Collecting Sewer, including the Grit Chamber. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1918: Intercepting Sewer Surveys made for proposed Frankford Creek High Level Intercepting Sewer from Wingohocking Street and Adams Avenue to Richmond and Luzerne streets, and the Tacony Creek Intercepting Sewer from I and Ramona streets to the City line at Cheltenham Avenue.

1918-1928: Cheltenham Sewage Negotiations with the Commissioners of Cheltenham Township regarding the city’s conveying and treatment of sewage from Cheltenham to the Northeast Sewage Treatment Works. This agreement was finalized in 1923, but not until the Tacony Creek interceptor was completed in 1928 (see below) was the hookup made. (See also note under 1888, which anticipated this agreement.)

1918: Effect of World War I on Public Works “Owing to the war the nation practically concentrated all its efforts on production of goods for the use of the allied countries engaged in the effort to end this most terrible of all conflicts, so that a lasting peace might be obtained. To obtain this object the National Government placed such embargoes on all classes of building materials that it became almost impossible to secure them for any but war purposes. The war industries also absorbed the greater part of the man-power of the nation not actually engaged in the fighting. These conditions caused such a scarcity and increased the cost of both material and labor to such an extent that it became practically prohibitive to attempt to carry on any work of municipal development and improvement.” The same influences also conspired to suspend most public works during World War II, 1941-45. (Source: Bureau of Surveys Annual Report for 1918, p.6)

1920: Beginning May 1, the flow of Wingohocking Creek was diverted through Frankford Creek High Level Collector and discharged into Frankford Creek at Leiper Street. Due to this diversion, the Philadelphia Felt Company, operating a mill partly by water power from a dam in Frankford Creek near Powder Mill Lane, claimed a loss in water power, the damages from which the City estimated at $42,065. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1920-1928: Industrial Wastes/Intercepting Sewer State Department of Health approved a permit for an extension of the Bingham Street Main Sewer from Adams Avenue to Tacony Creek, as well as for the temporary discharge into Tacony Creek of industrial wastes from the factory of the Electric Storage Battery Company, but one of the conditions of this permit was that the Frankford Creek High Level Intercepting Sewer be “expeditiously” extended north from I and Ramona streets so the Bingham Street sewer could be connected with it. This did not happen until April 26, 1928, when the Bingham Street sewer, carrying waste from Electric Battery Co., among many other sources, was finally connected with Tacony Creek Intercepting Sewer for treatment at the Northeast Sewage Treatment Works. This is just one small example of the ramifications of not doing this work: the battery wastes can be multiplied many times, when one takes into account all the industries along the creek. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1922: Opening of Frankford Elevated transit line proves a boon to shops and stores in Frankford and helps spur residential development in Northeast Philadelphia.

1923: On October 29, the Northeast Sewage Treatment Works and Frankford Grit Chamber placed in operation by Mayor J. Hampton Moore. The initial flow to the plant consisted of 25 million gallons per day (mgd) from Wingohocking Creek. It would be almost thirty years before the other two treatment plants called for by the 1914 comprehensive plan are brought on line.

1923: Frankford Creek City officials consider “walling in the stream as a closed sewer,” but faced with objections from local residents, this idea is dropped. (Source: Bulletin editorial, March 28, 1923)

1925: State Pressures City to Finish Tacony Creek Interceptor The State Sanitary Water board issued a permit for the construction, but not the use of, proposed sewers in the Tacony Creek Watershed. “It will be the policy of the Sanitary Water Board to withhold approval of the use of new sewers in the Tacony Creek Watershed until construction work is started on the Tacony Creek Intercepting Sewer.” (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1925: Industrial Wastes In its permit approving construction of the Tacony Creek Intercepting Sewer, the Sanitary Water Board also advised the City “to cause a survey to be made of all industrial wastes now being admitted to the Public Sewers in order to determine which are harmful as aforesaid so that corrective measures may be adopted & also in order that proper means may be taken to prevent the admission of harmful industrial wastes to the public sewers from establishments thereafter erected or operated.” Since most sewers simply entered into the City’s rivers or streams, industrial waste–whether emptied into City sewers or dumped directly into streams–was an important source of pollution. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1928: Tacony Interceptor Completed; Wingohocking Obliterated “The year 1928 saw the completion of the Tacony Creek Intercepting Sewer to the County Line, and the connection with the sewer system of Cheltenham Township. A meter has been installed for measuring the sewage entering the City of Philadelphia from Cheltenham Township, as provided for in the agreement entered into in 1923, by which the City of Philadelphia conveys and treats the sewage of Cheltenham township at the cost provided for in the agreement. The completion of this intercepting sewer made possible the diversion of sewage from Tacony Creek, which was formerly delivered from the sewer systems at Ashdale Street, Bingham Street and Champlost Avenue….The completion of the main Wingohocking sewer removed the last section of Wingohocking Creek, formerly a landmark in that section of Philadelphia, which was the main drainage channel from the heart of Germantown over to Frankford Creek.” A report from the Bureau of Surveys in 1926 noted, with some pride, that once completed, the sewer “will permit the filling in of the creek valley and provide ground for building development over many acres.” (Source (unless noted otherwise): Bureau of Engineering and Surveys report, in First Annual Message of [Mayor] Harry A. Mackey…for the year ending December 31, 1928, page 152)

1932: Interceptors and Great Depression Minor work still needed to complete Frankford Intercepting System, but the continued slowdown due to the Great Depression put off that and most other public works projects. A letter from one disgruntled businessman to Mayor J. Hampton Moore in 1932 referred to the creek as the ‘Frankford Sewage Canal.” (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1937: Northeast Works At Capacity In a permit from the Department of Health for, among other work, intercepting chambers in the Upper and Lower Level Frankford Interceptors, one of the conditions placed upon completion of the work was the following: “When the intercepting devices along Frankford Creek are completed they shall be placed in operation to such an extent that they will diminish pollution of Frankford Creek but not overload the exiting Northeast Works….The work of increasing the capacity of the Northeast Works shall be given priority status.” (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1937: Clean Streams Legislation June 22: State Legislature passed Public Law 394, “to preserve the purity of the waters of the Commonwealth for the protection of public health, animal and aquatic life, and for industrial consumption and recreation.” (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1938: Interceptors Intercepting chambers built at 15 points along the Upper and Lower Frankford Creek Low Level Collectors. (1943 Chronology has list). It is unclear whether this completed the work of connecting sewers to these interceptors, and ended the sewage pollution of Frankford Creek. In any case, the industrial pollution of the creek continued with direct discharges from various factories. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1938-1942: Financing/Government Loan and grant applications Loan and grant applications were made by the City as follows: to Federal Emergency Administration in 1938, for $37.9 million to carry on the sewage disposal program, and to provide flood relief along the Wingohocking Sewer system; in 1941, to the U.S. Defense Public Works Administration, for $42.7 million grant for sewage treatment works, pumping stations, grit chambers, intercepting and collecting sewers, and the restoration of Frankford Creek; and in 1942, to the U.S. Public Works Reserve Administration for $57 million to complete sewage disposal and treatment system and restore Frankford Creek. All applications were denied, and the sewage disposal system remained unbuilt. (Source: 1943 Chronology)

1941: Sewage Pollution On October 17, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered an investigation investigate to determine if water and sewerage facilities in Philadelphia were a menace to the health of defense workers. On October 25, the Interstate Commission on the Delaware River (Incodel) petitioned the Sanitary Water Board to bring action against Philadelphia to stop its discharge of 350 million gallons a day discharge of raw sewage into the Schuylkill and the Delaware Rivers. Incodel declared the ending of Philadelphia sewage pollution “is by far the most important project in the entire Delaware River Basin.” (Source: 1943 Chronology and newspaper articles)

1940-45: Financing/Sewer rents The City, under pressure from the State, passes an ordinance to impose fees for sewer use, called a “sewer rent,” in order to generate income to back a bond issue of $42 million to complete the sewerage system. The State Supreme Court declared the rent illegal, and it did the same in 1941. The City’s persistence finally paid off when an April 30, 1944 sewer rent ordinance was upheld by the State Supreme Court on October 30, 1945. This made it possible for the city to borrow $81.6 million more for public improvements than would have been the case if the sewer rents not been imposed, and allowed the sewage disposal project finally to be completed in the early 1950s. (Sources: 1943 Chronology and various newspaper articles)