Written in 2010 to provide historical background for a storm relief sewer project that was completed that year.

To download a PDF slideshow of Adam Levine’s photos of this storm relief project, taken in the tunnel as it neared completion, click here.

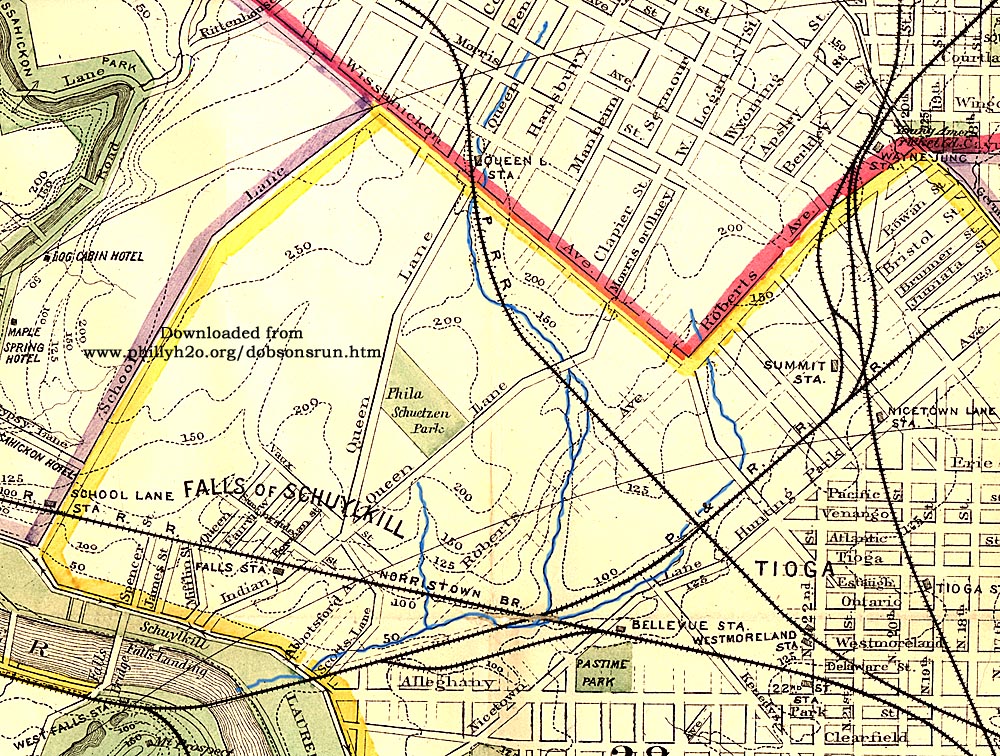

A small Schuylkill River tributary called Dobson’s Run once drained a watershed consisting of parts of East Falls, Nicetown and Germantown. Like many such natural streams, in Philadelphia and most other cities in the world, it was systematically buried in a sewer beginning in the 1890s, and now appears only on the Philadelphia Water Department’s sewer maps. Old city maps, however, still show this small stream, which entered the Schuylkill on the east side, north of Laurel Hill Cemetery and just about where the Twin Bridges of Roosevelt Boulevard now stand.

Dobson’s Run had two branches. One had its source near the Queen Lane railroad station in Germantown, and the other branch began near the old Nicetown Steel Works in the city’s Nicetown neighborhood. These two small streams joined about 1-¾ miles east of the Schuylkill and eventually flowed through the property of John and James Dobson, who owned and operated many textile mills in the Philadelphia area. The Dobson mill east of Ridge Avenue in “Falls Village” (as East Falls was originally called) used the water from Dobson’s Run for industrial processes and for waste disposal. This mill was one of the largest carpet factories in the world in the latter decades of the 19th century.

To provide water for the mill, the natural stream was dammed above the Dobson complex, backing up a large pond behind the dam. Some of the water from this pond was diverted through the plant in a number of small canals or ditches, called mill races. Below the factory complex the races carried the water–tainted with chemicals and wastes from various carpet-making processes–back into the natural stream, which flowed into the Schuylkill River in this polluted state. One observer in 1882 said the sand and gravel at the mouth of the stream was stained with dyes from the Dobson factory.

Since the stream carried its pollution into the so-called “Fairmount Pool”–the stretch of the Schuylkill River above the Fairmount Dam which was a major source of drinking water for the City–several attempts were made over the years to get the Dobson’s and other factory owners to stop dumping their wastes into Dobson’s. One such lawsuit, filed by the Fairmount Park Commission in 1880, alleged that discharges from the mills were polluting the city’s water supply. In response, the expert hired by the Dobsons, a Penn professor, stated that Dobson’s Run was contaminated by ordinary sewage “in far larger proportion than the impurities which are added to it as a result of the manufacturing operations carried on along its bank.”

Though this hired expert was clearly biased in favor of the Dobsons, he was probably correct in his assessment. Sewers and outhouses from the Dobson’s mill, from other businesses, and from the expanding residential neighborhoods upstream, all emptied their wastes into the creek, causing a serious health nuisance. This was a problem not only in East Falls, but all along the stretch of the Schuylkill River above the Fairmount Water Works. Protecting the city’s water supply from such pollution was the main reason that Fairmount Park was created just after the Civil War. This protection became even more important as the population exploded in the second half of the 19th century and the city added more water supply pumping stations along the Schuylkill at Spring Garden, Belmont, Queen Lane and Shawmont.

The ultimate solution to the problem was to put Dobson’s Run into a large, separate, storm sewer, to carry the stream flow and any stormwater directly into the Schuylkill River. Sewage from households and businesses along with wastes from industries in the small valley were captured in a smaller, separate, sanitary sewer before the sewage and industrial wastes could reach Dobson’s Run. The sanitary sewer connected with an intercepting sewer that paralleled the Schuylkill River, capturing all the sewage flow from Shawmont downstream to Fairmount, dumping it into the river below the Fairmount Dam. This work began in the early 1880s and, in the valley of Dobson’s run, continued at least until 1912, when the three pictures above appeared in the annual report of the Bureau of Surveys of the Philadelphia Department of Public Works. The interceptor also carried all of the sewage from the Wissahickon Creek valley, as well, including rapidly growing portions of Chestnut Hill, Mt. Airy, and Germantown, whose development was spurred, in part, by construction of the Chestnut Hill branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad, completed in 1884.

2010 Flood Relief Project PROJECT

In natural areas, rainfall that does not infiltrate (soak into) the ground runs off on the surface, finally making its way into the nearest stream. In urban areas, where many surfaces such as rooftops, streets, sidewalks and parking lots are “impervious” to water, rainfall has little opportunity to soak into the ground. Instead most of it flows through storm drains and downspouts to sewers.

Street flooding in urban areas occurs when the sewer system is unable to carry off this flow, causing the water to back up onto the surface. In the Dobson’s Run sewershed–the area of land that drains into this syetm–the sewers are not large enough to carry away the stormwater, which backs up above the storm drains during heavy rains. In such cases, repeated flooding often occurs in low points in the neighborhood.

Relief sewers, to provide additional capacity for the stormwater, are often necessary in these areas, and many have been built in the city in the past 100 years.The Dobson’s Run Stormwater Relief Sewer, to be built upstream of the flood-prone areas, will increase the drainage capacity of the sewers in the watershed. By capturing part of the storm flow and carry it directly to the Schuylkill River, it should relieve flooding in the valley of the former Dobson’s Run.

For more on the relief sewer project, see this entry and this follow-up on Chris Dougherty’s excellent blog, The Necessity for Ruins.