This page is a work-in-progress.

All 108 maps are posted, but many still need to be described. If you would like to help us describe these maps, or have additional information for those already described, please contact me.

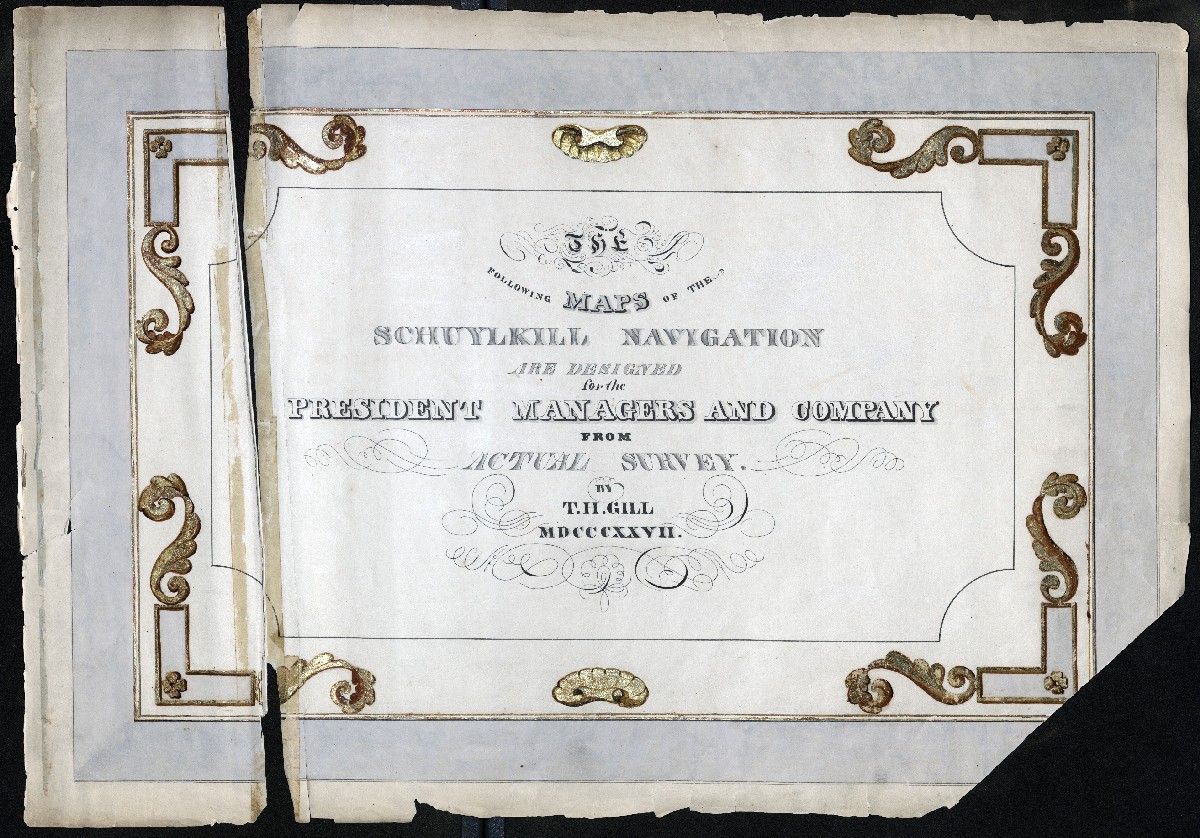

TITLE

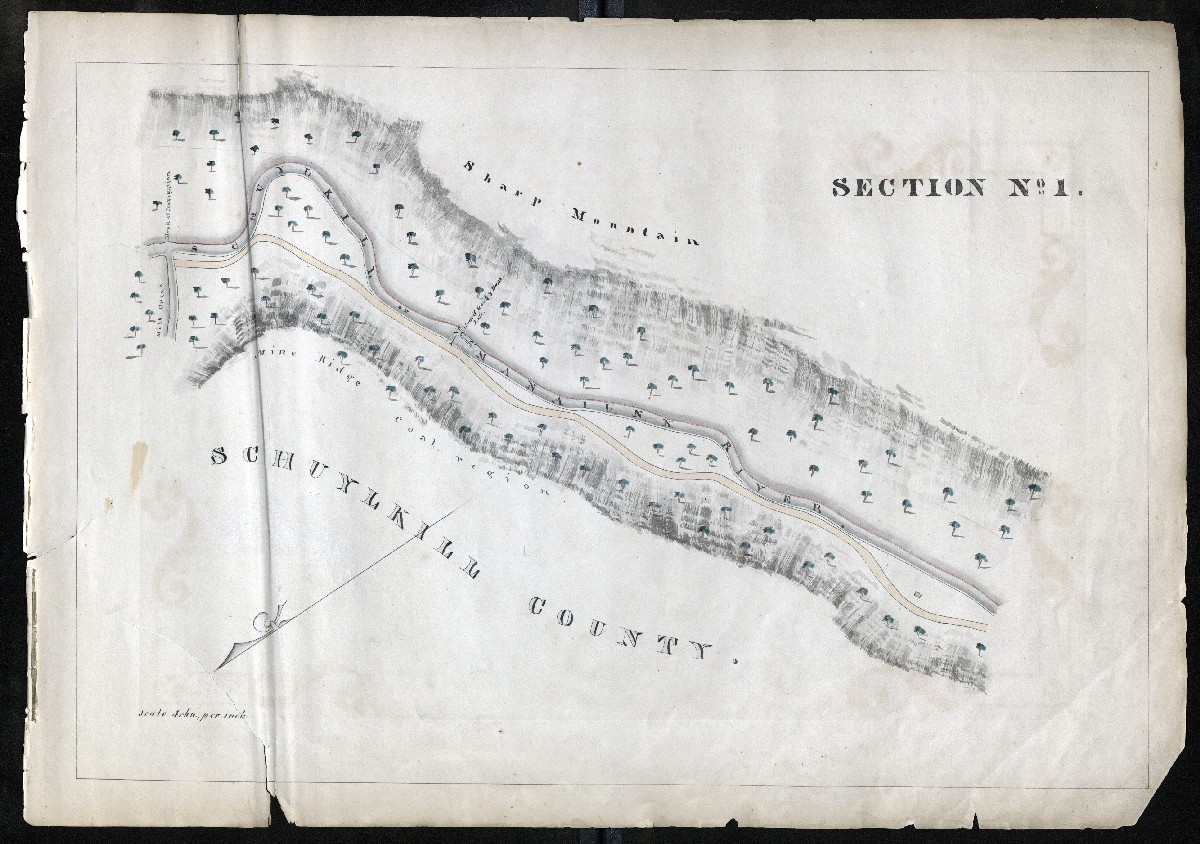

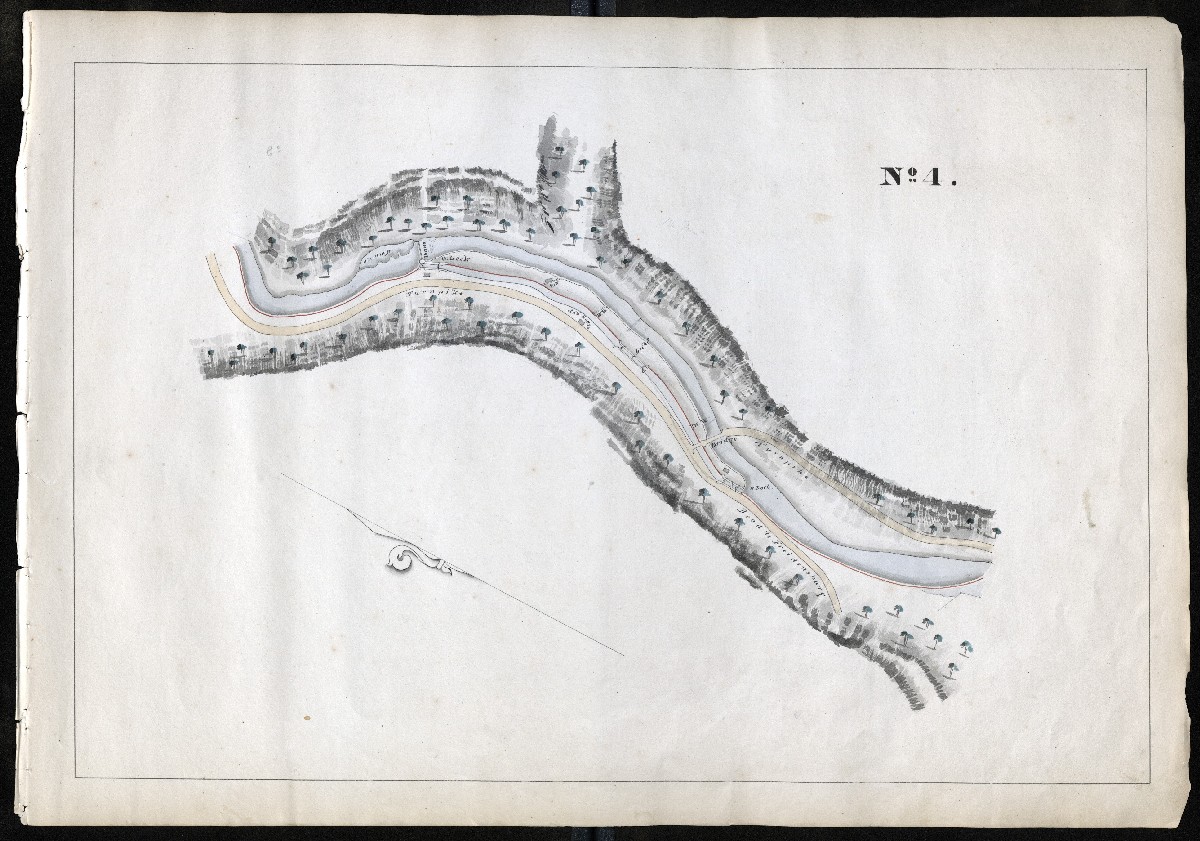

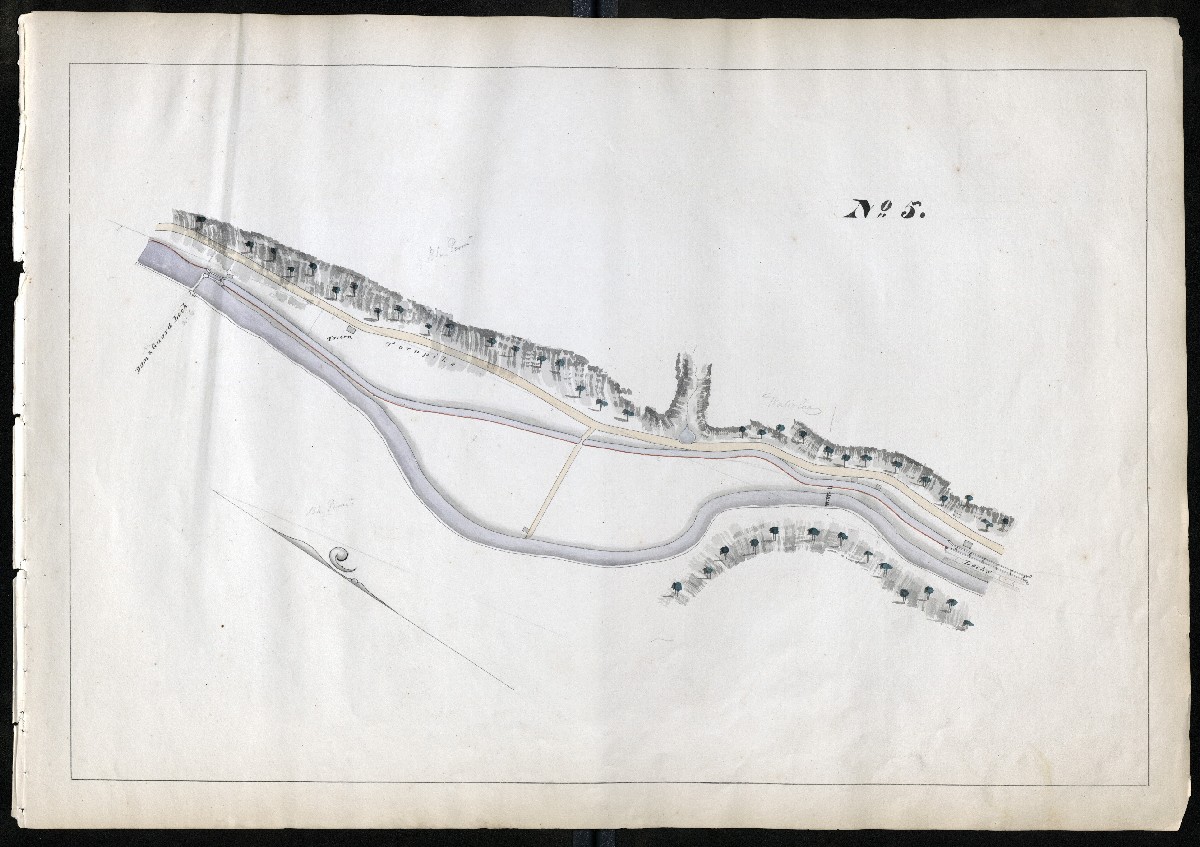

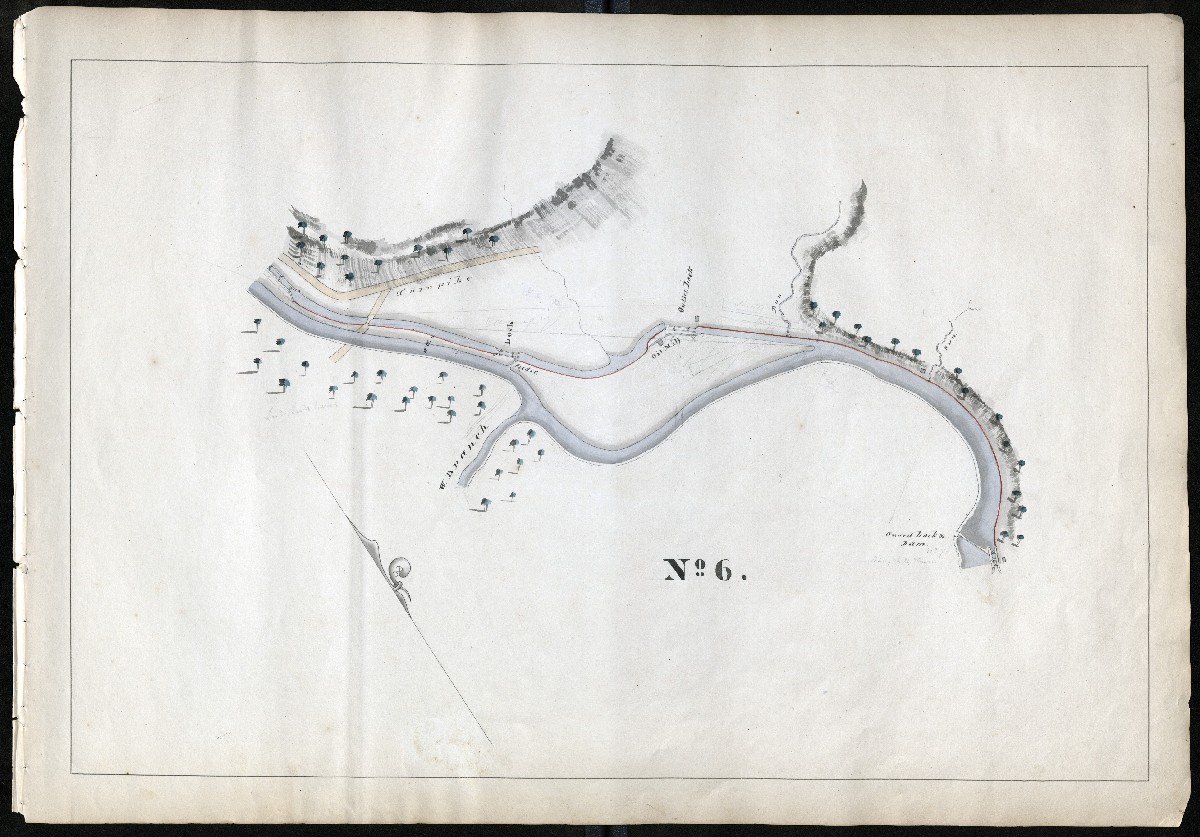

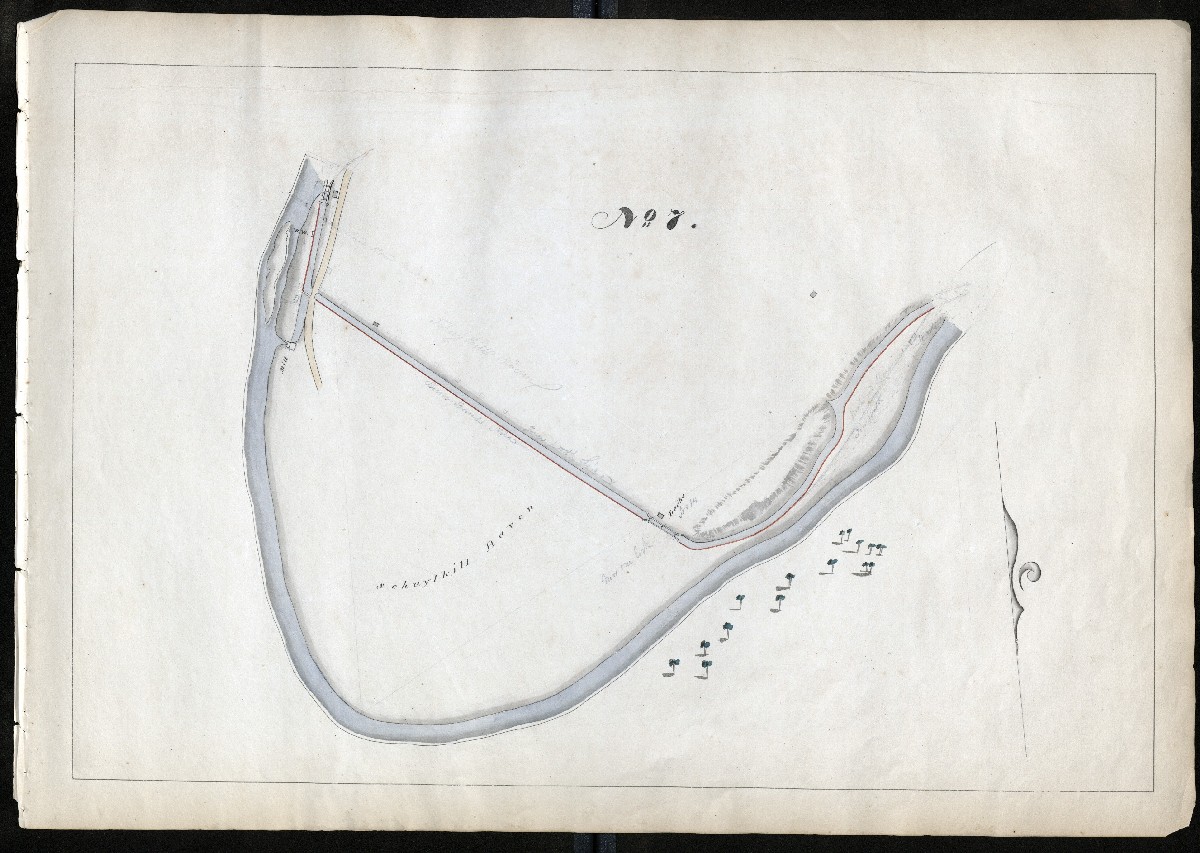

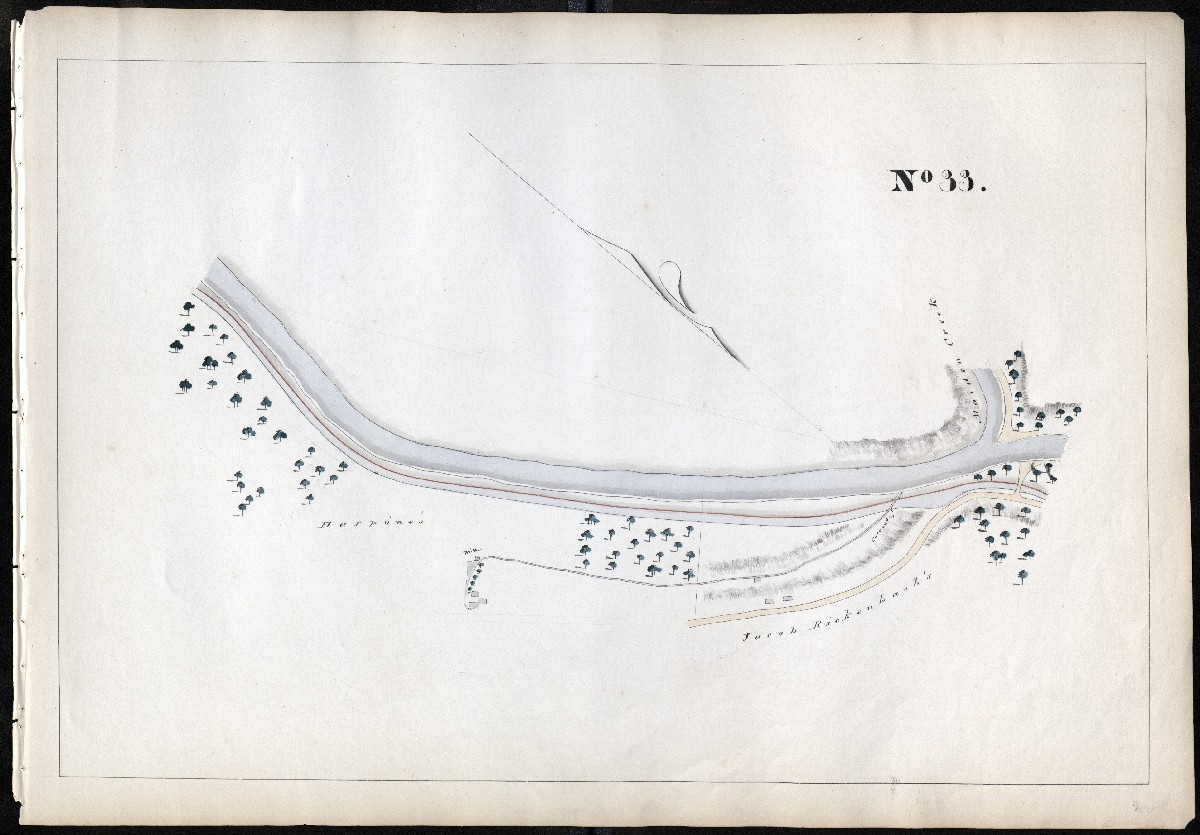

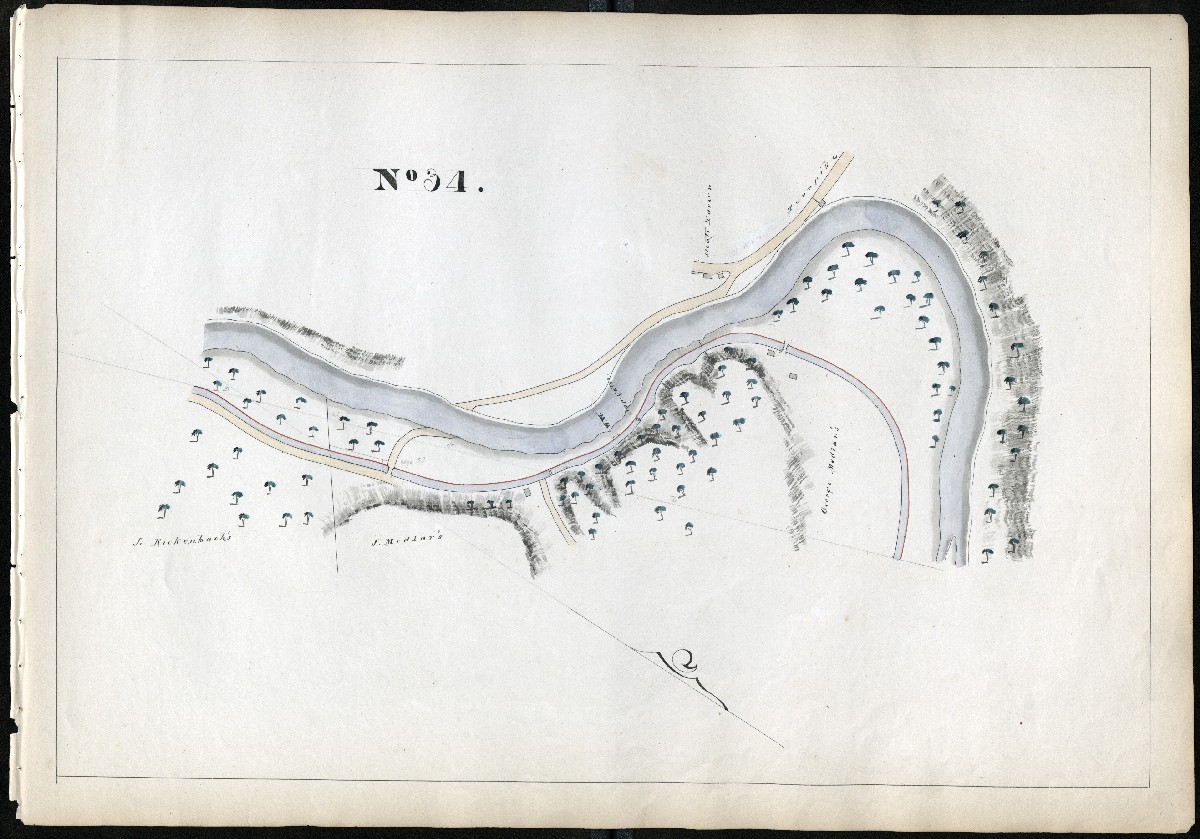

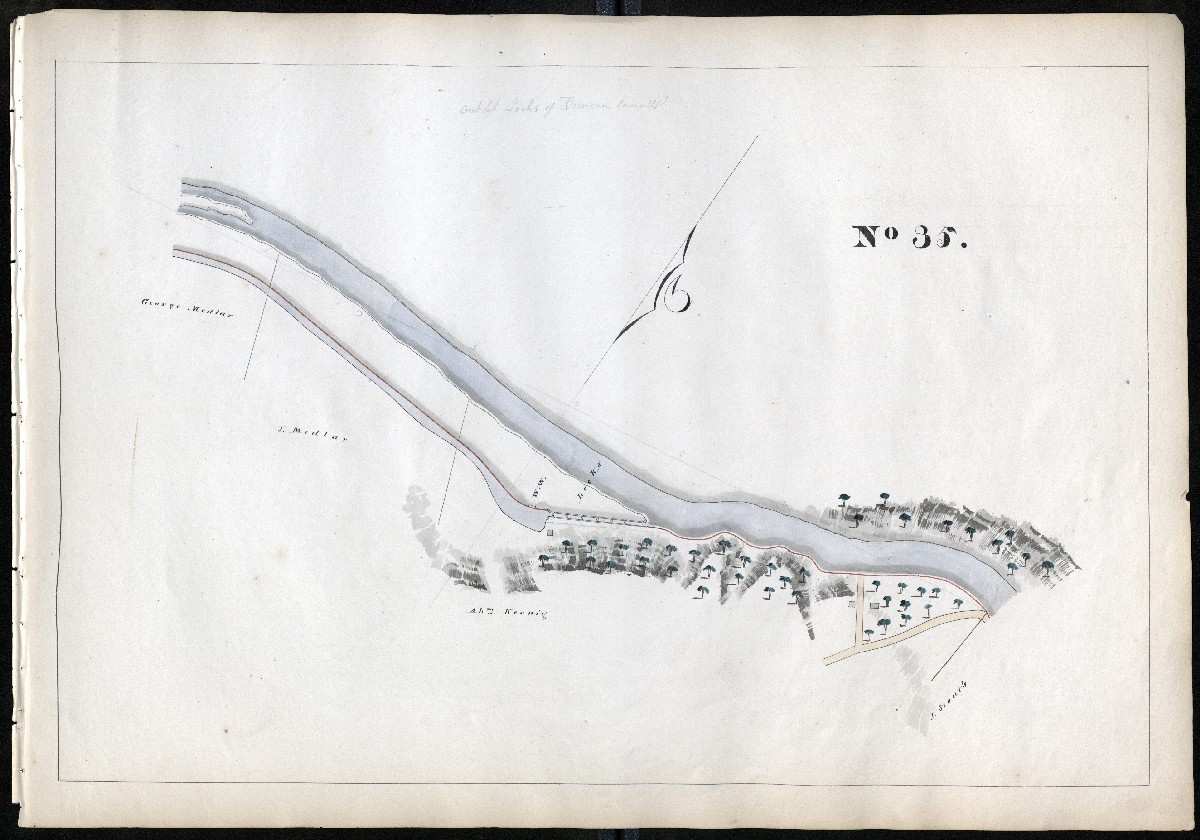

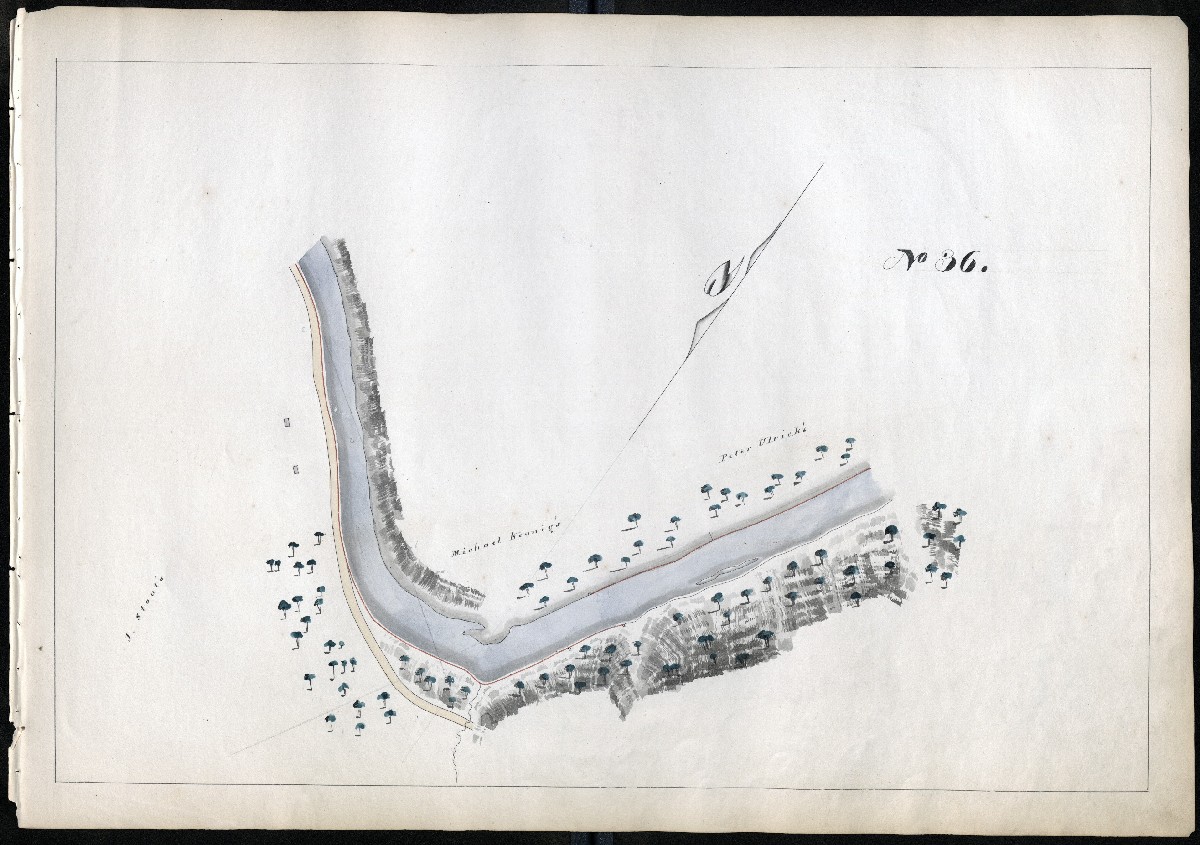

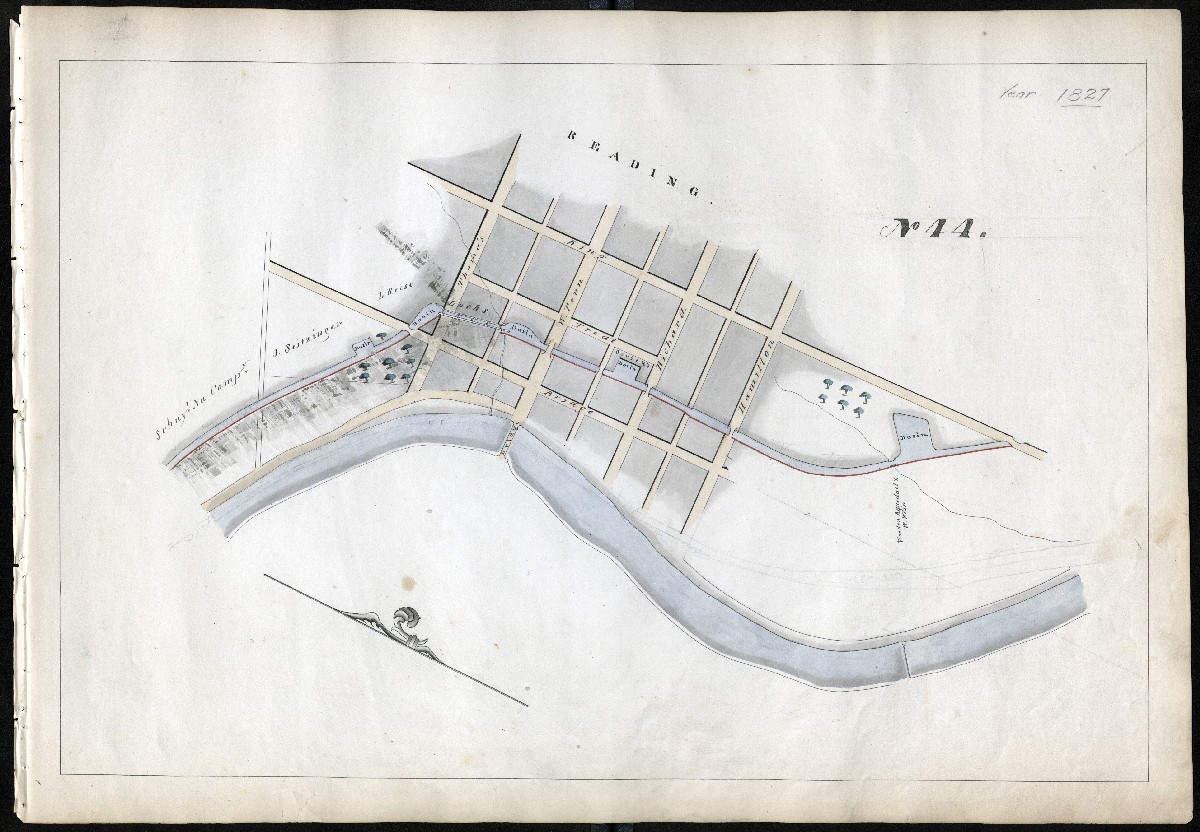

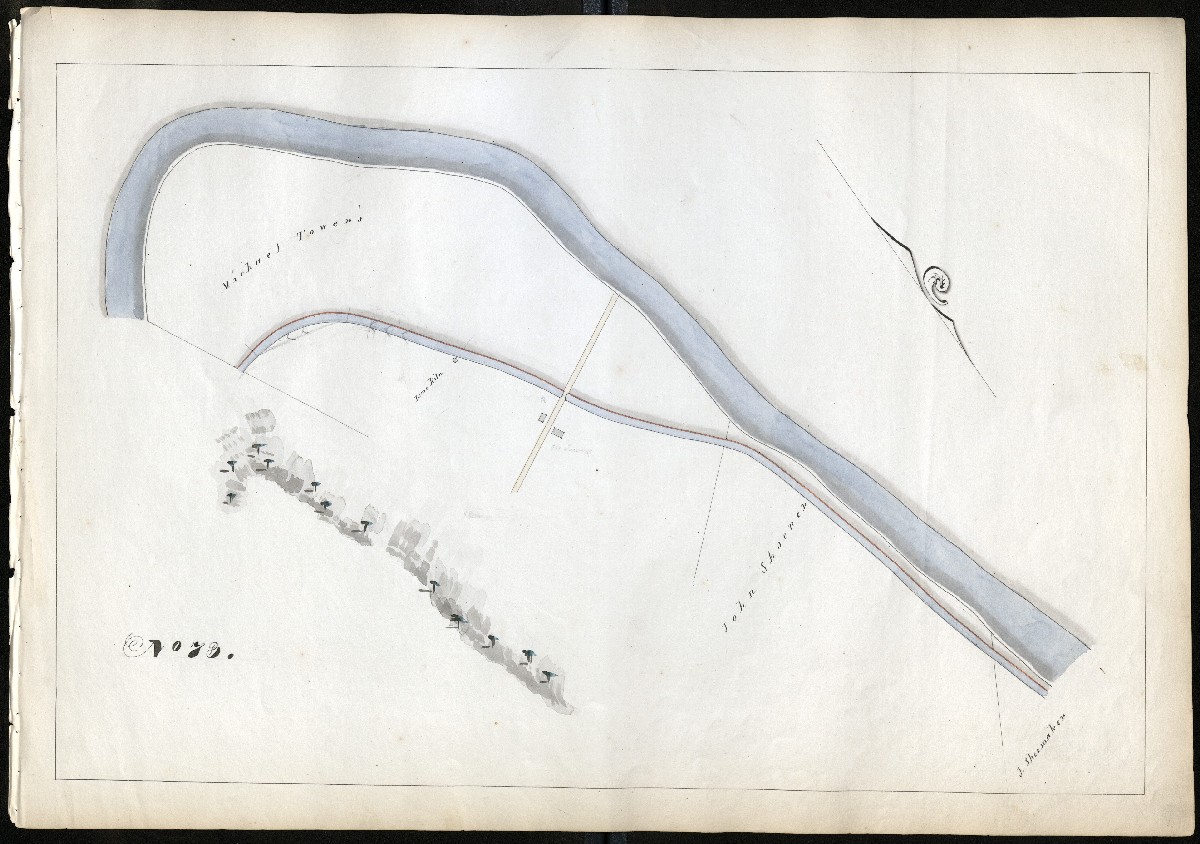

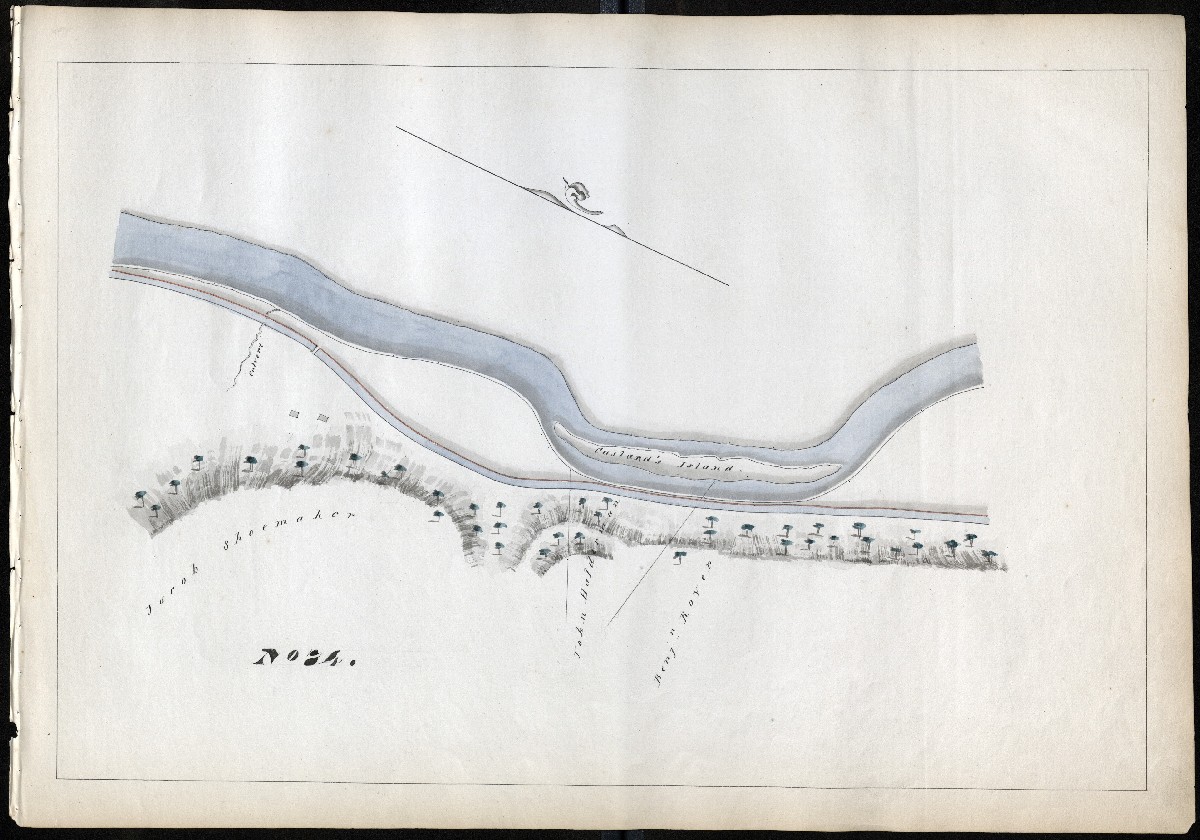

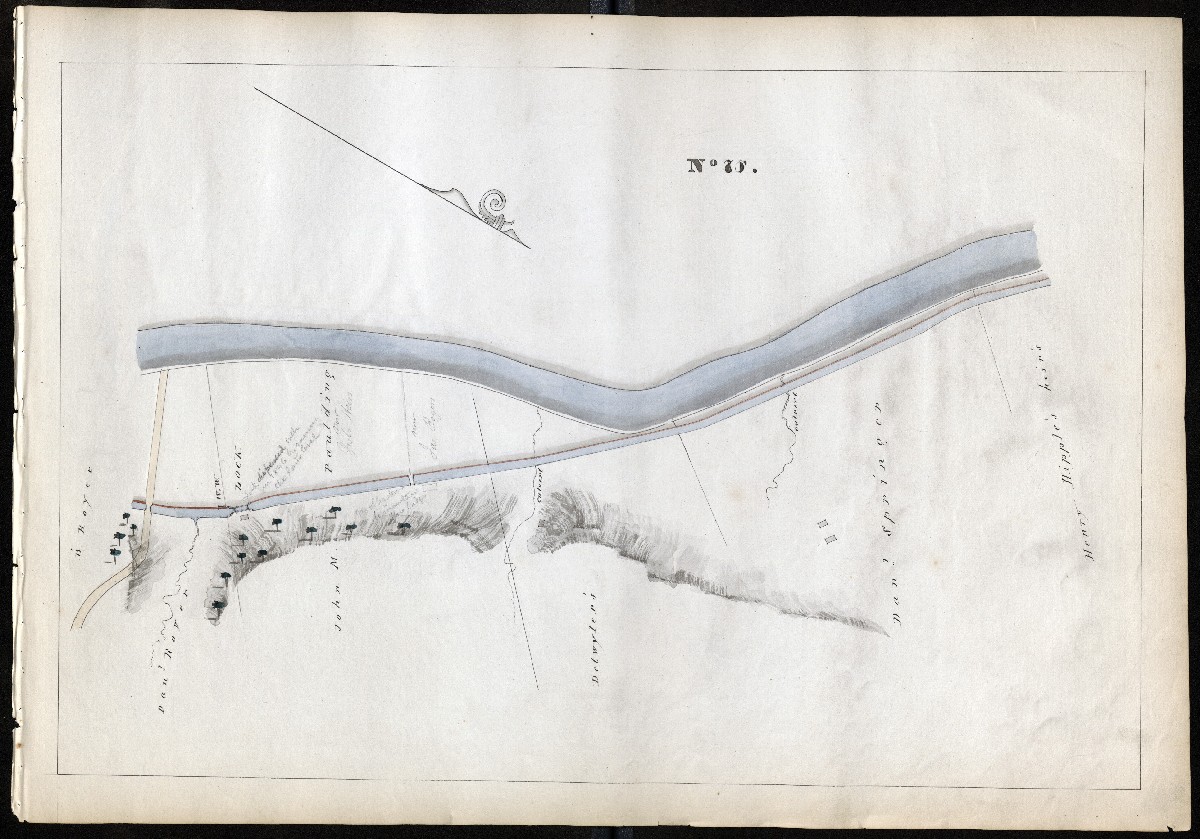

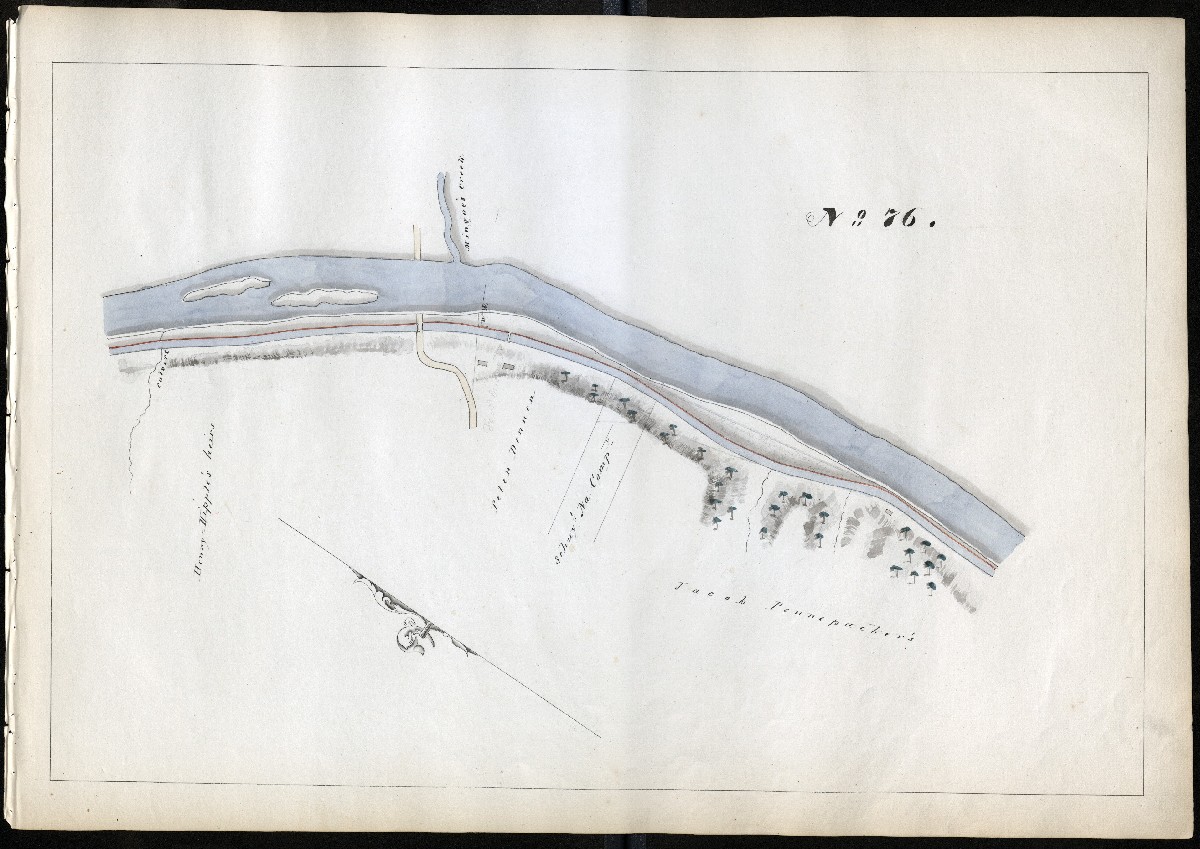

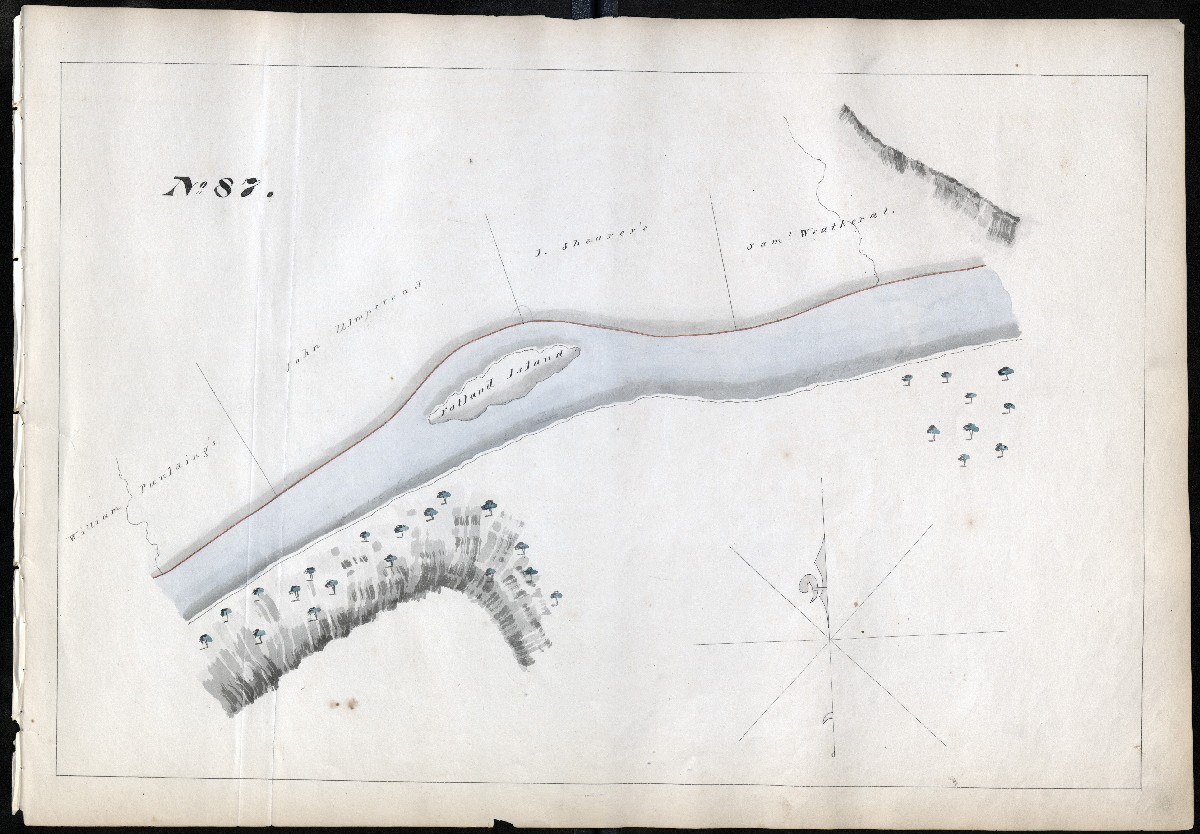

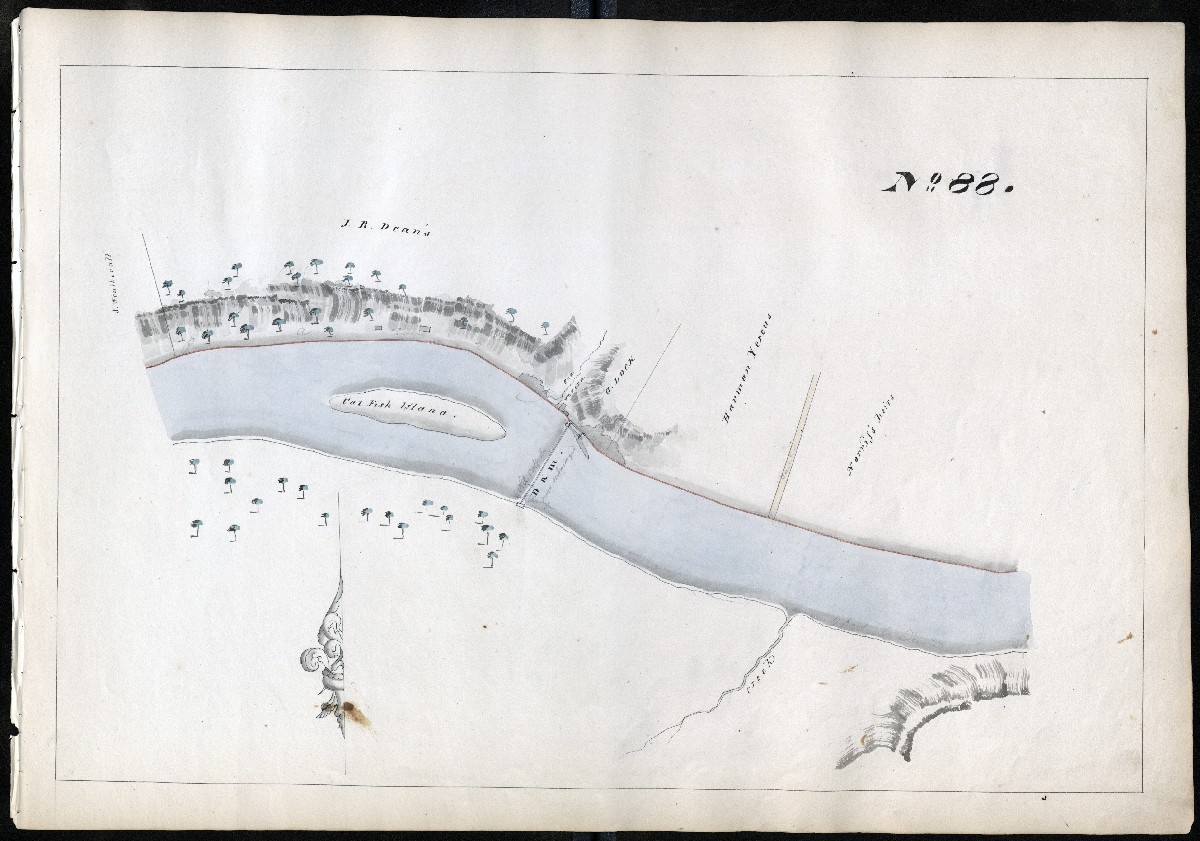

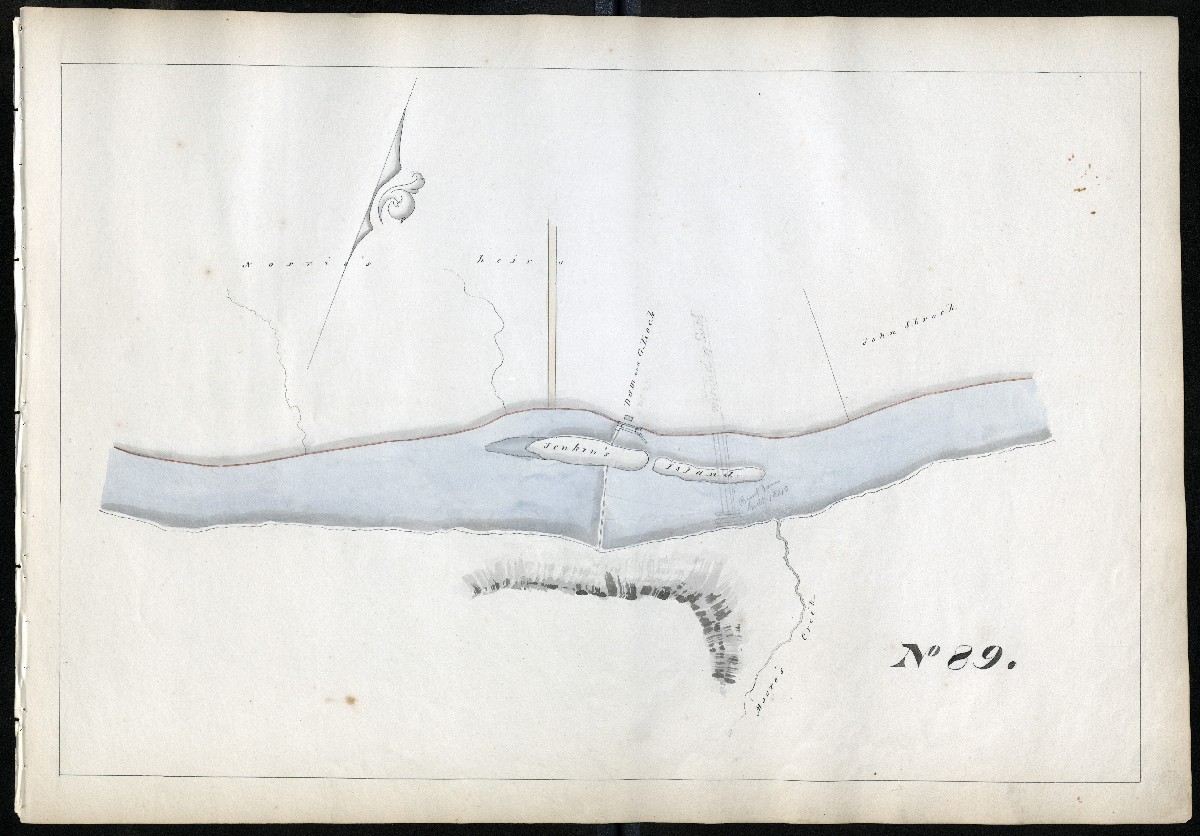

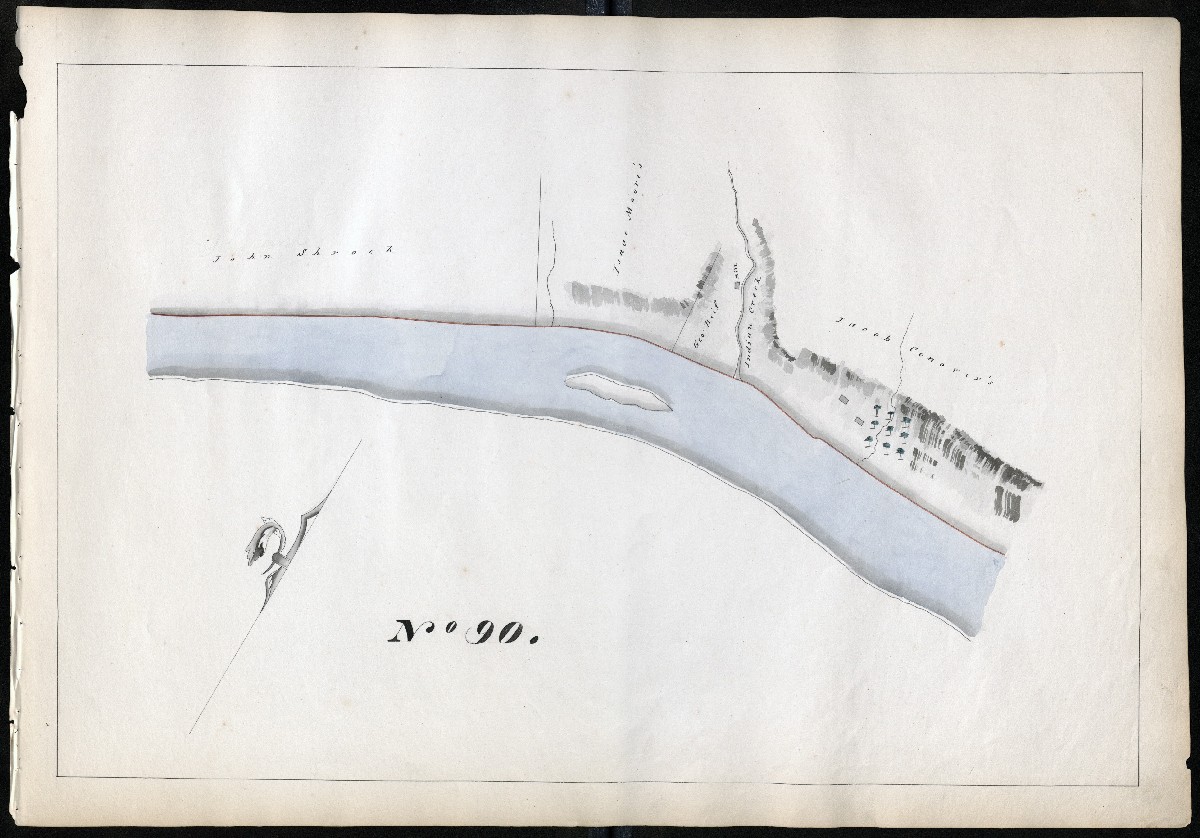

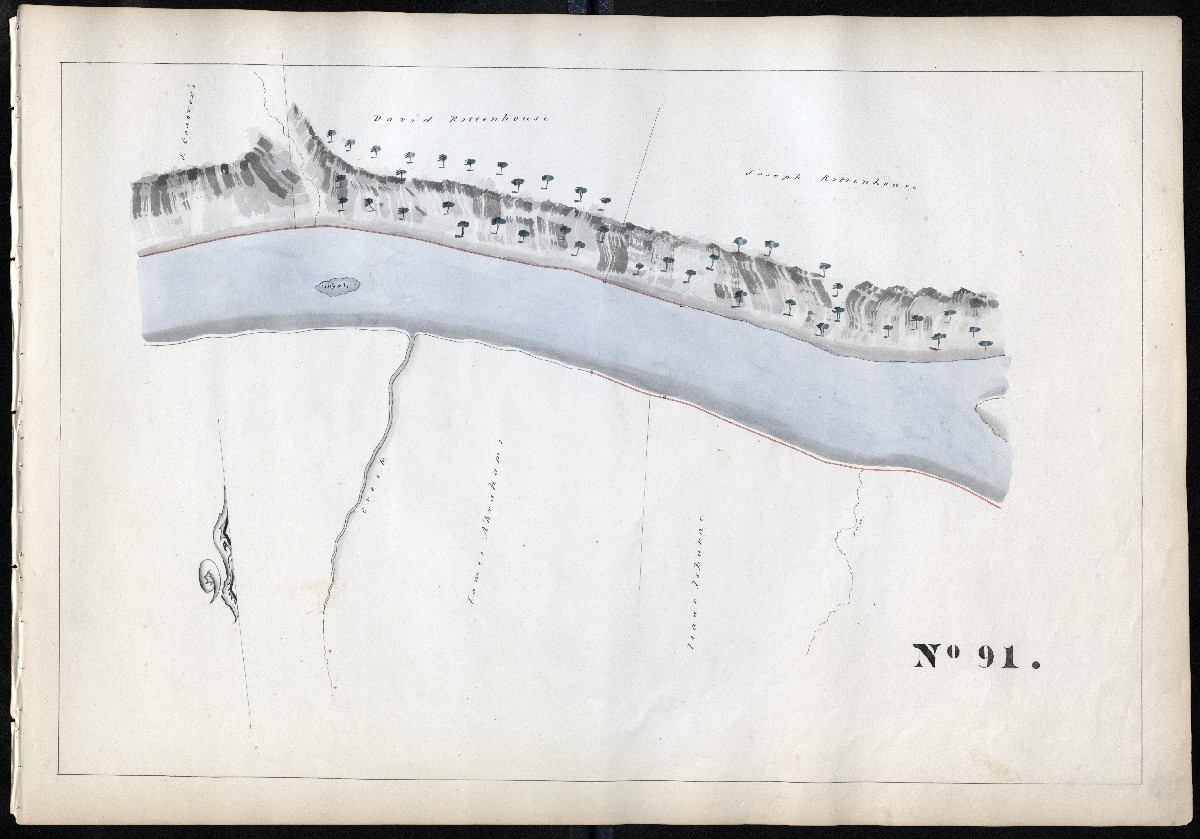

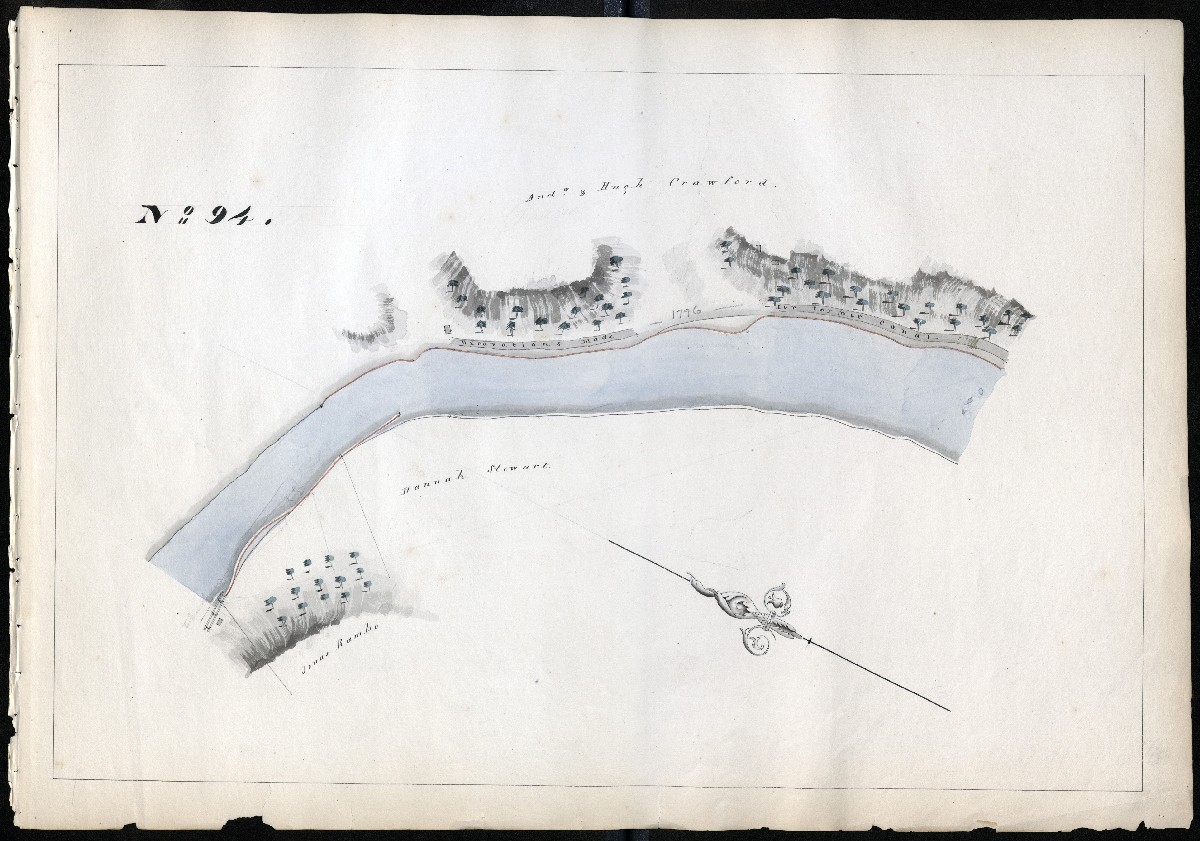

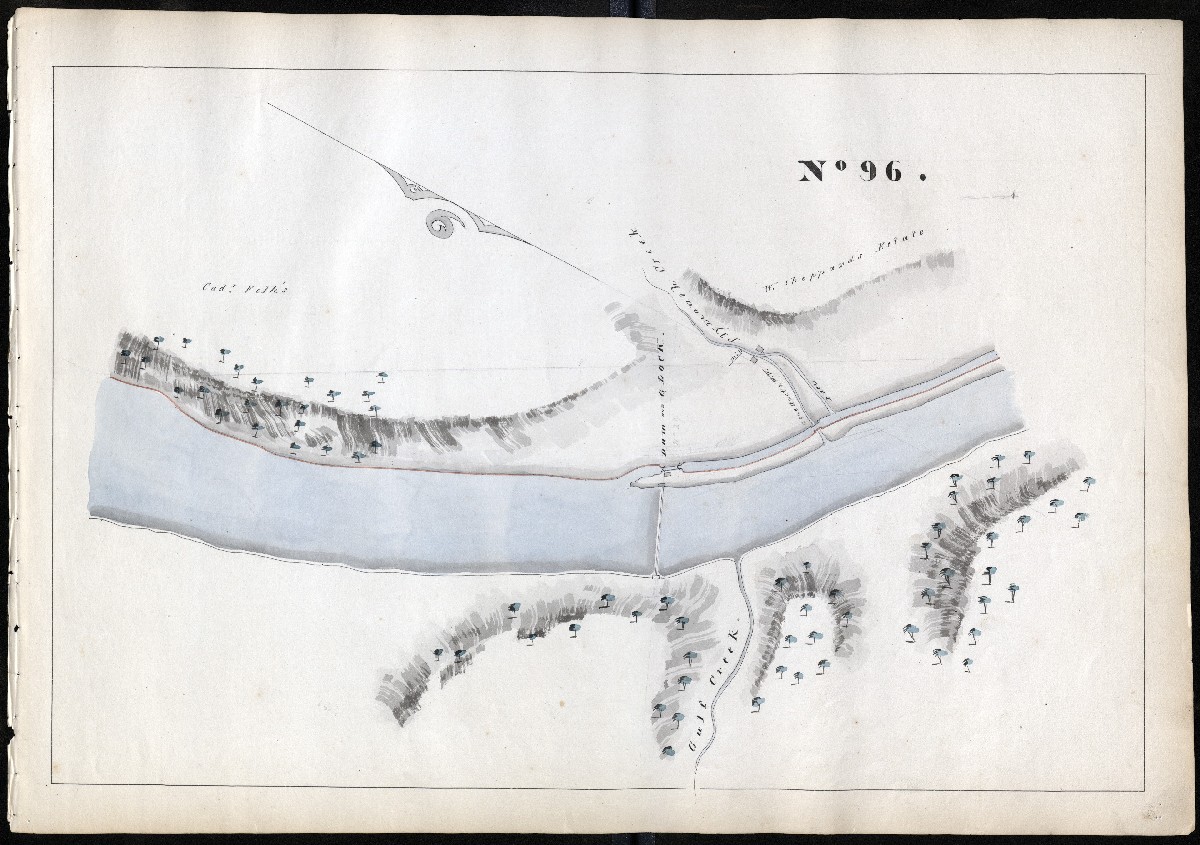

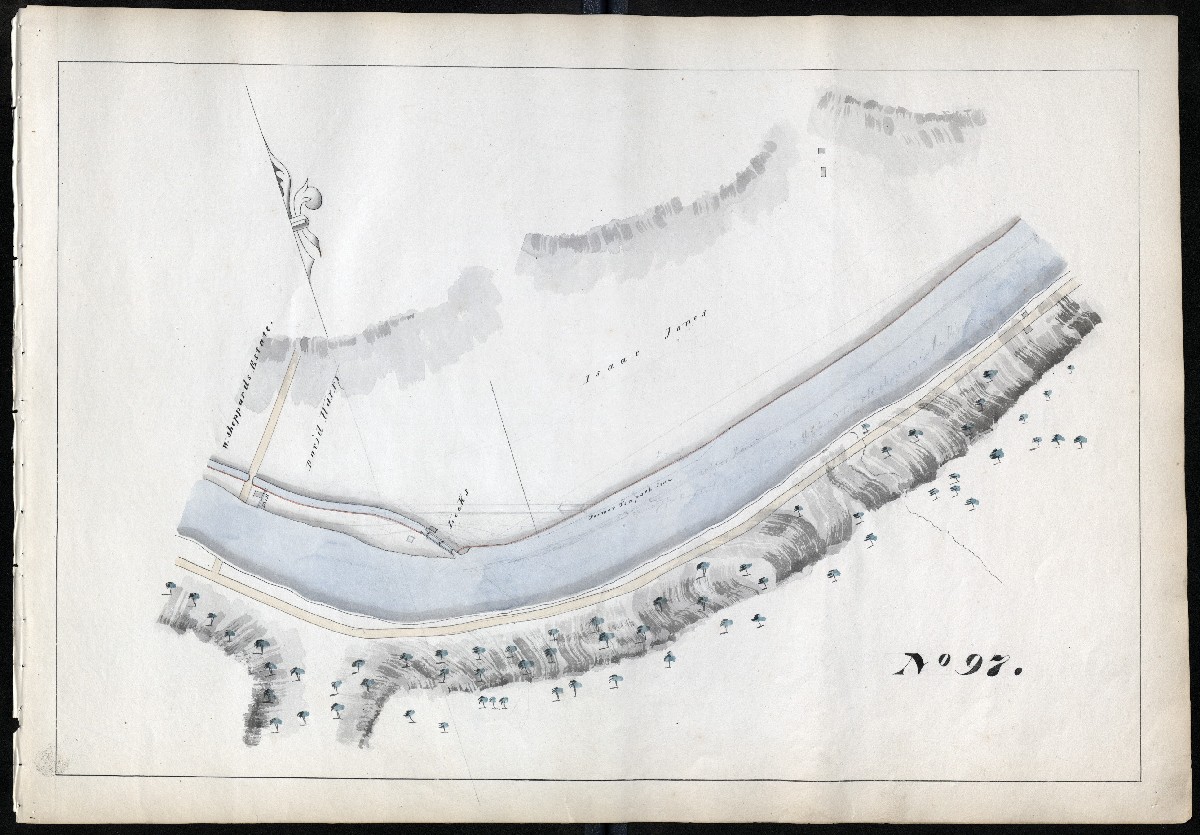

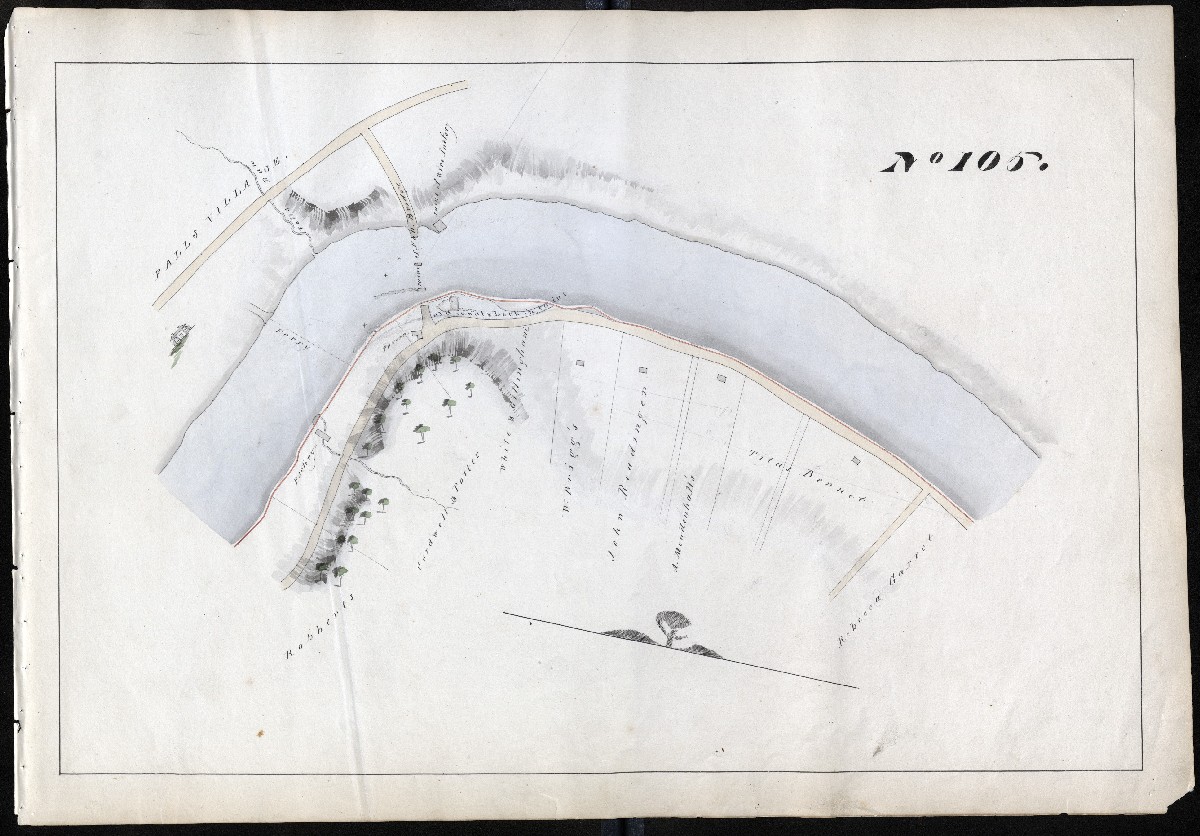

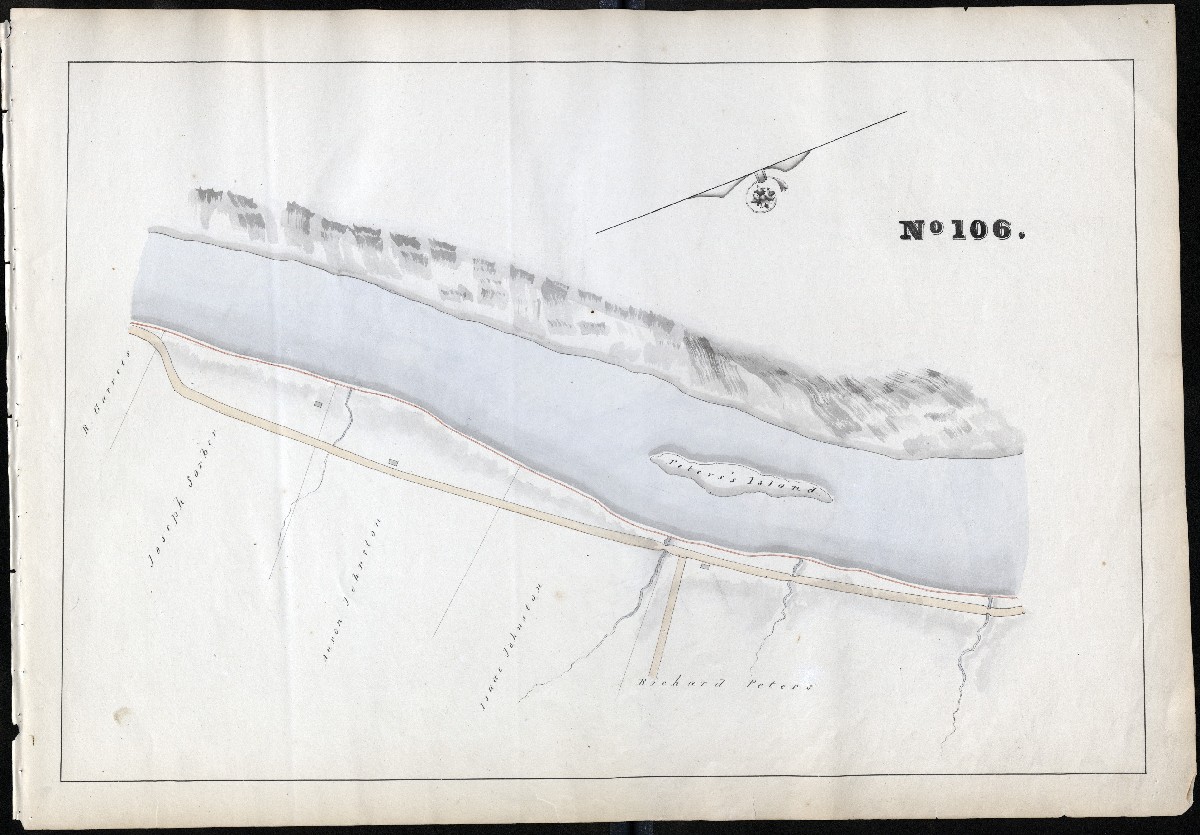

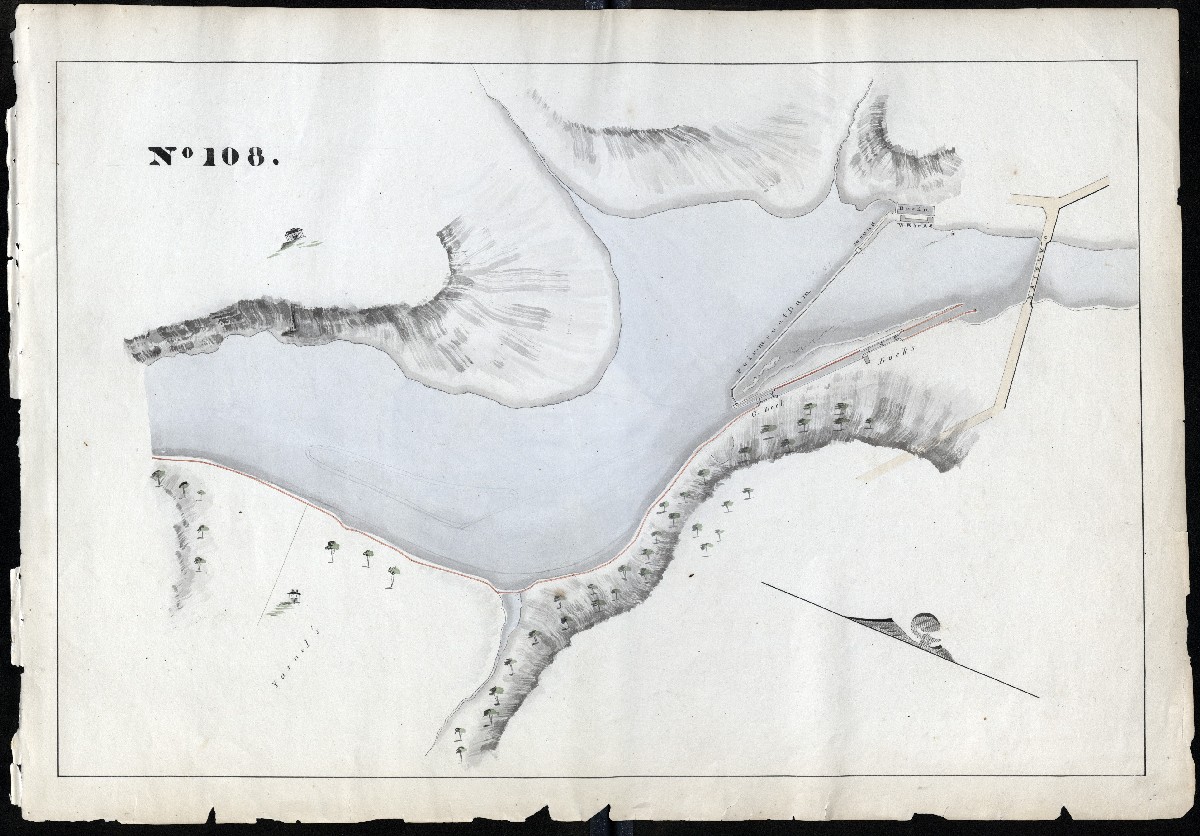

The following maps of the Schuylkill Navigation are designed for the President, Managers and Company from actual survey. By T. H. Gill, MDCCCXXVII

DATE

1827

DETAILS

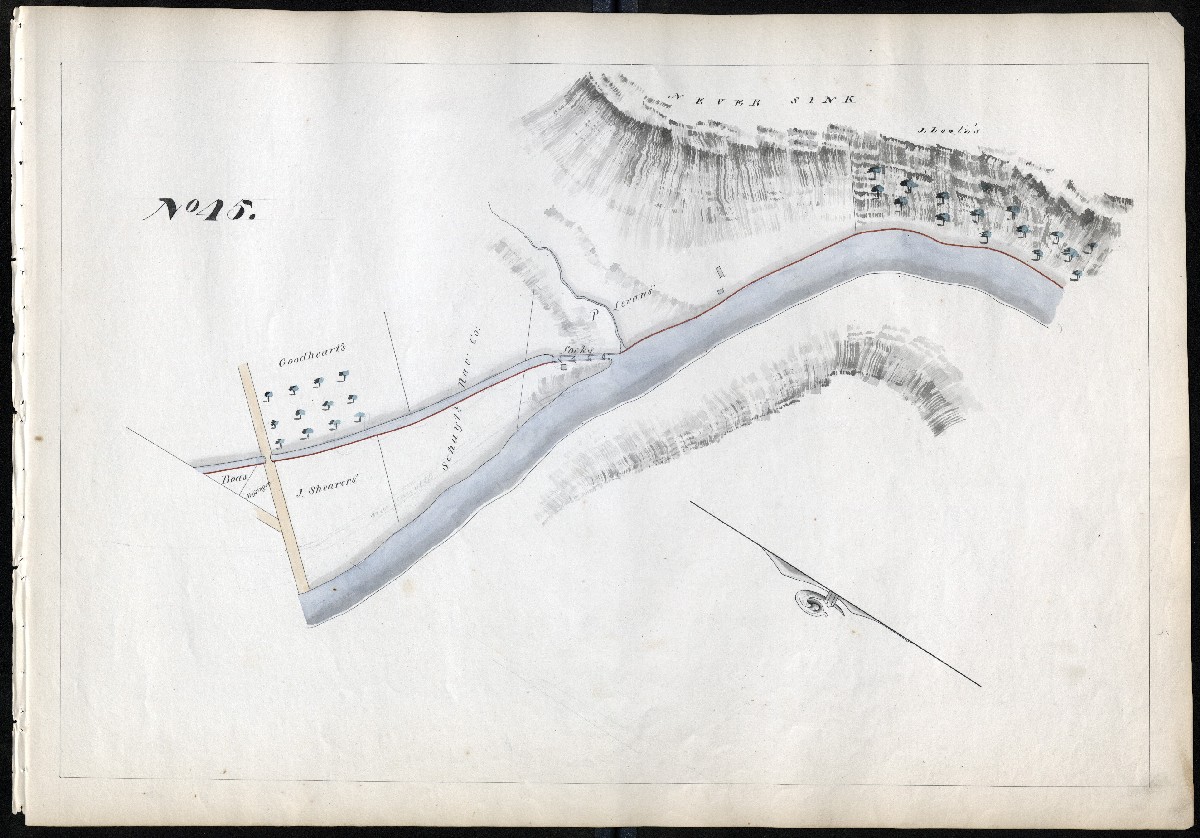

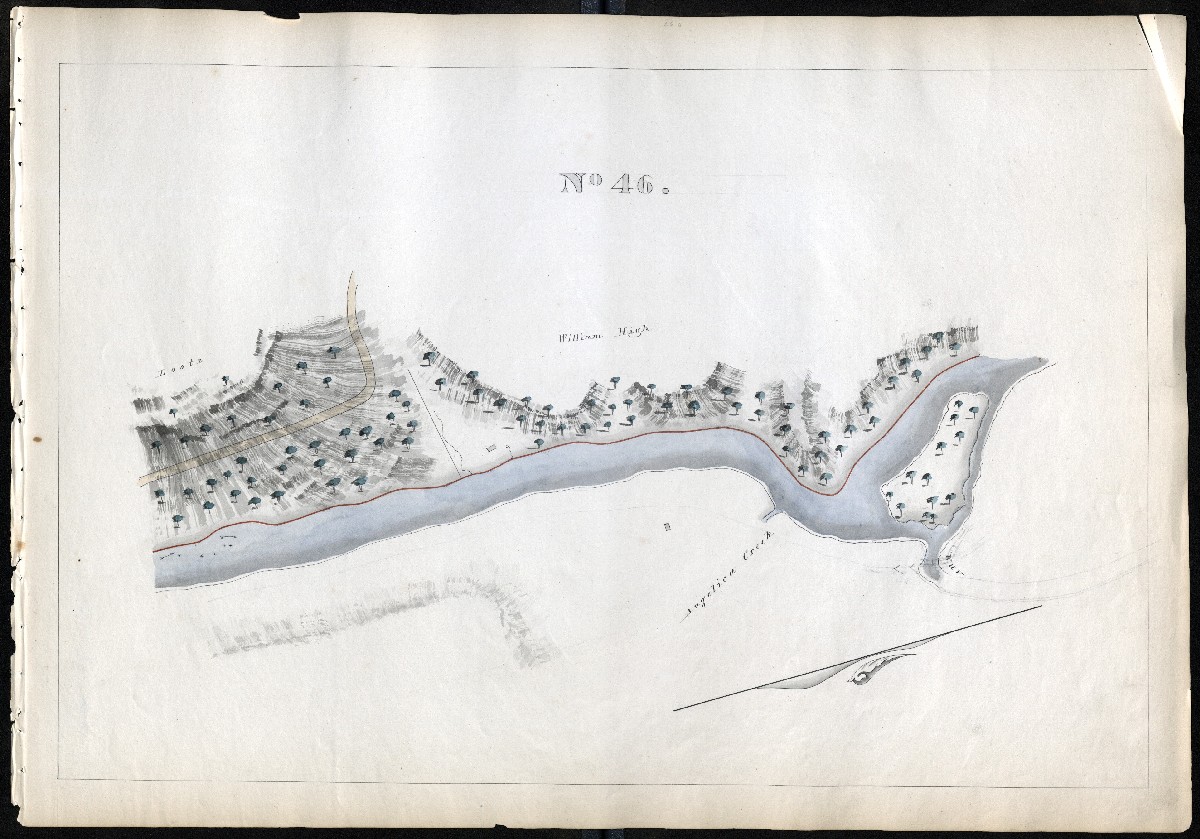

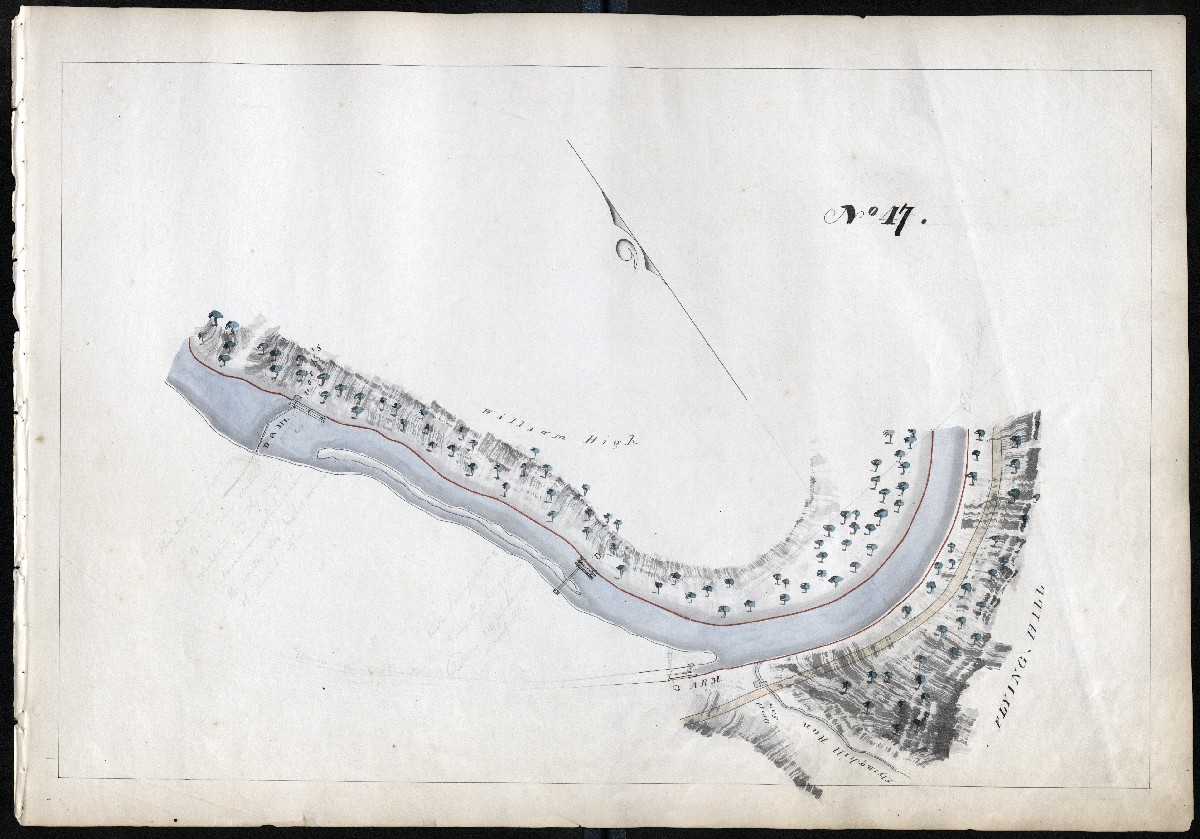

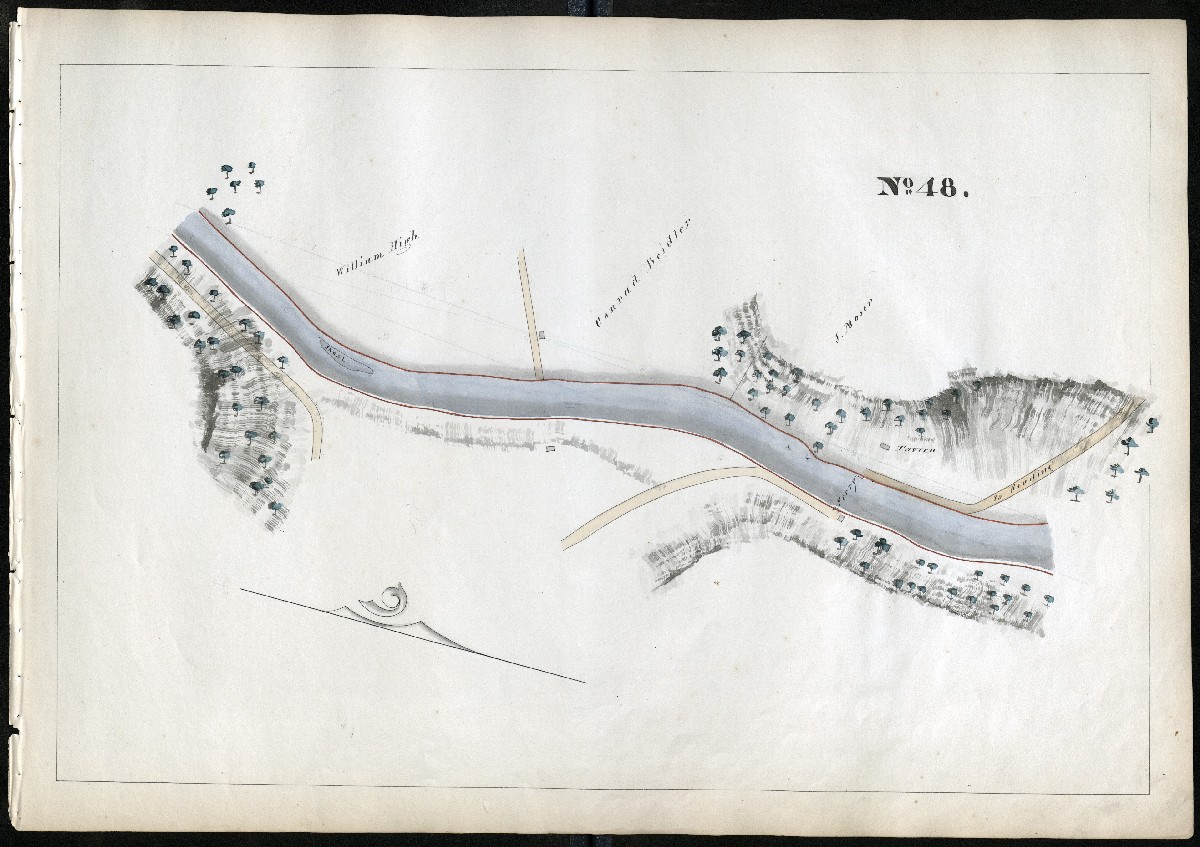

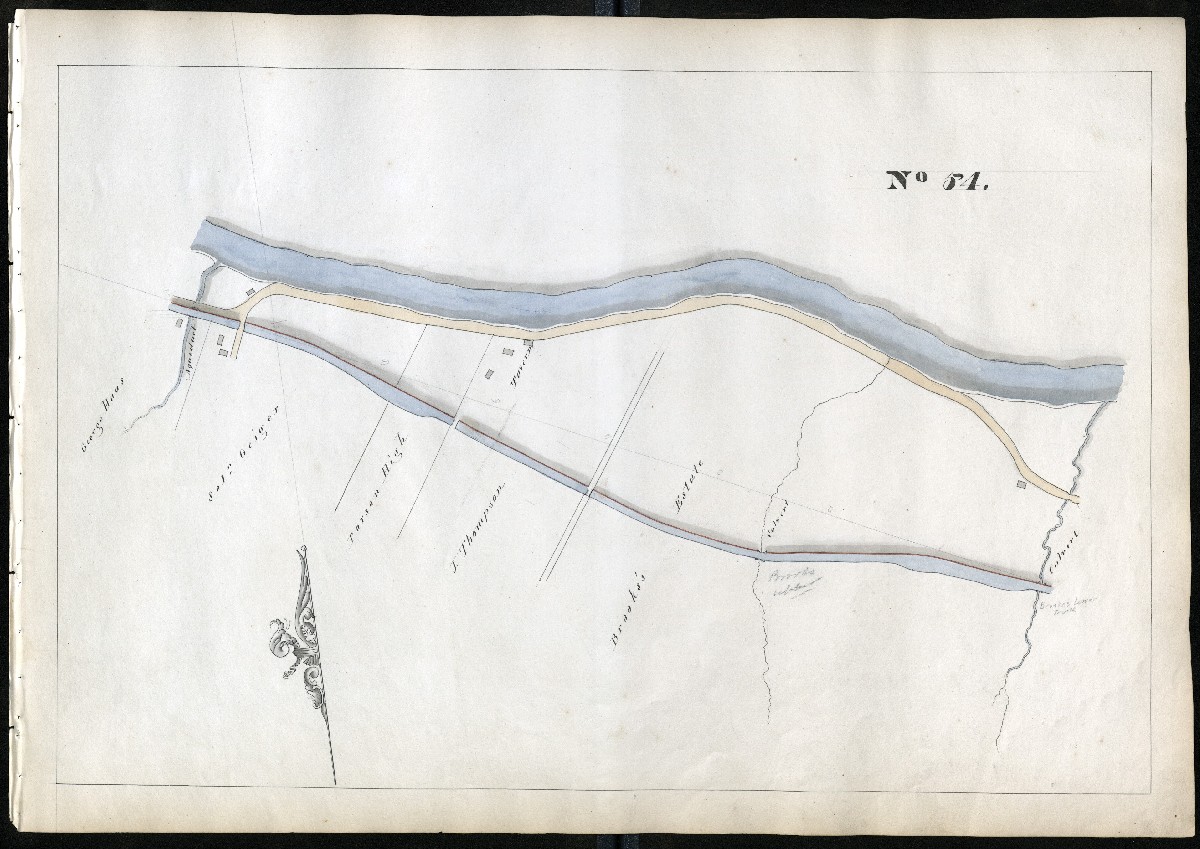

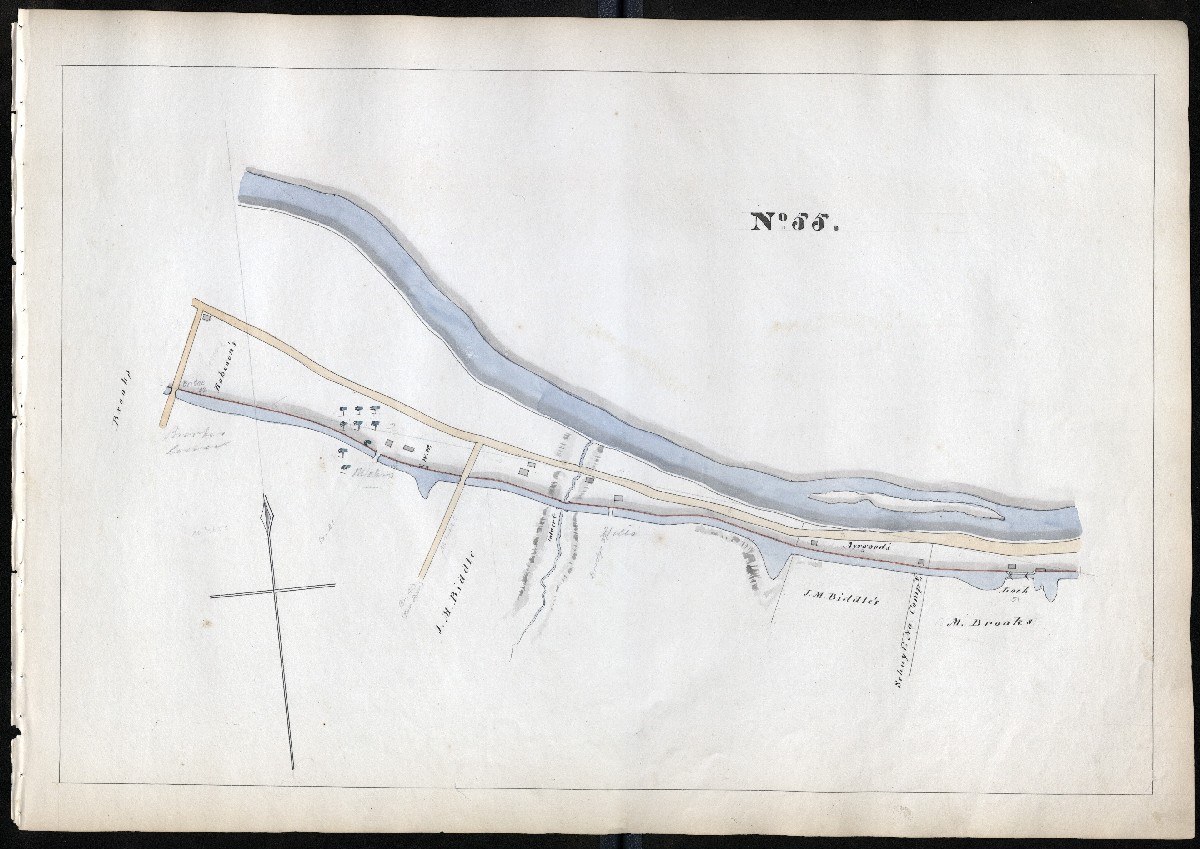

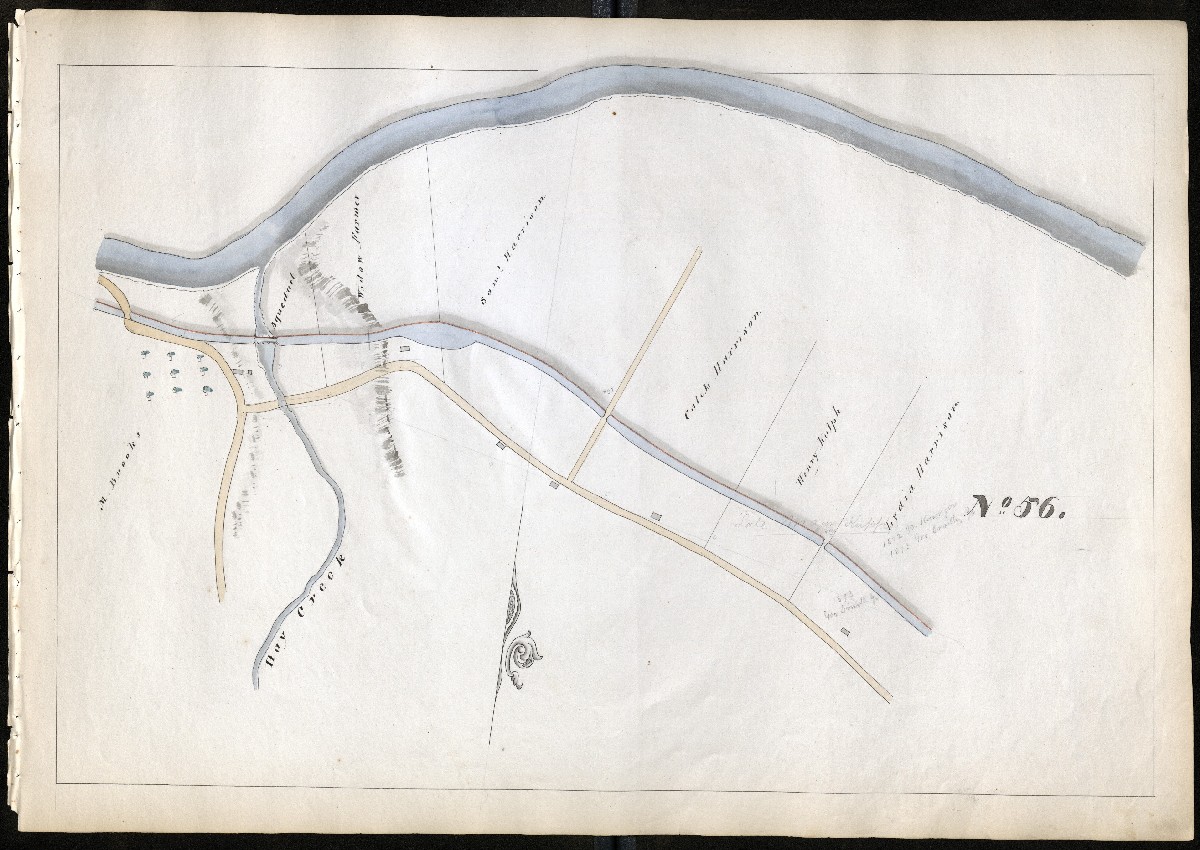

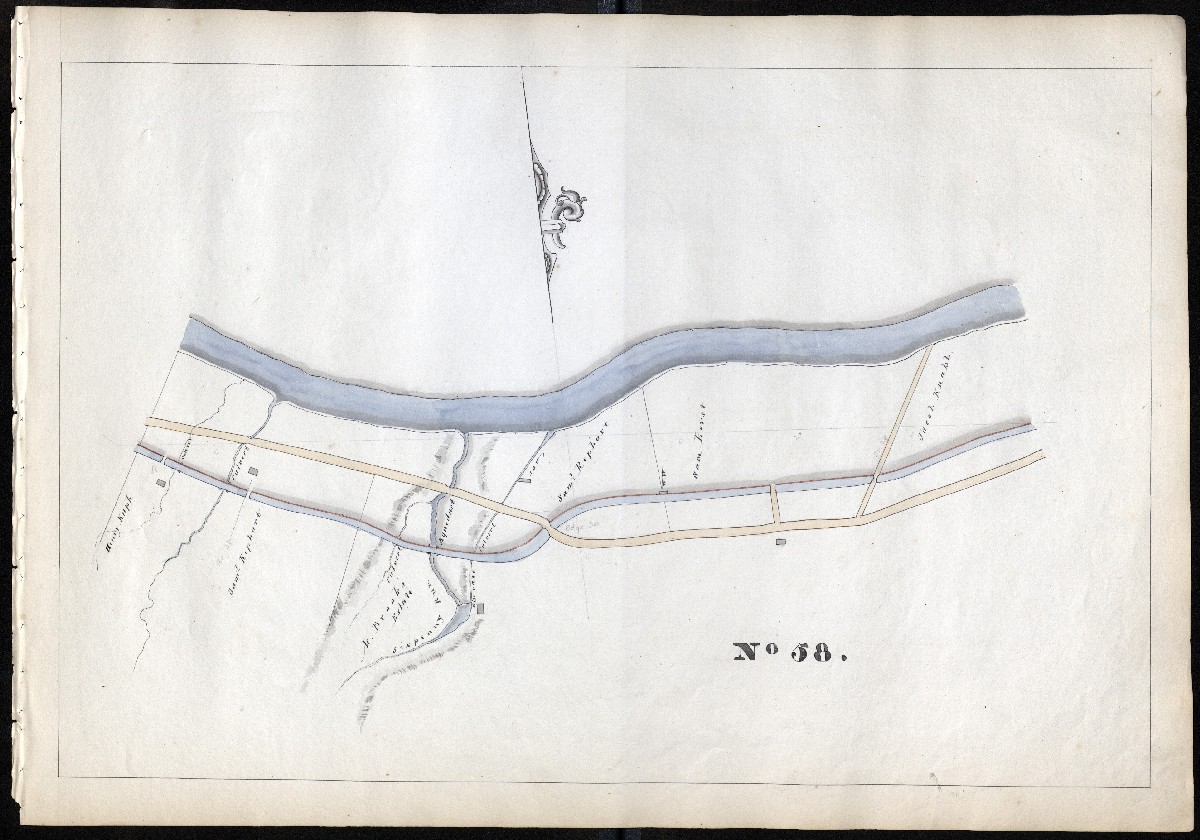

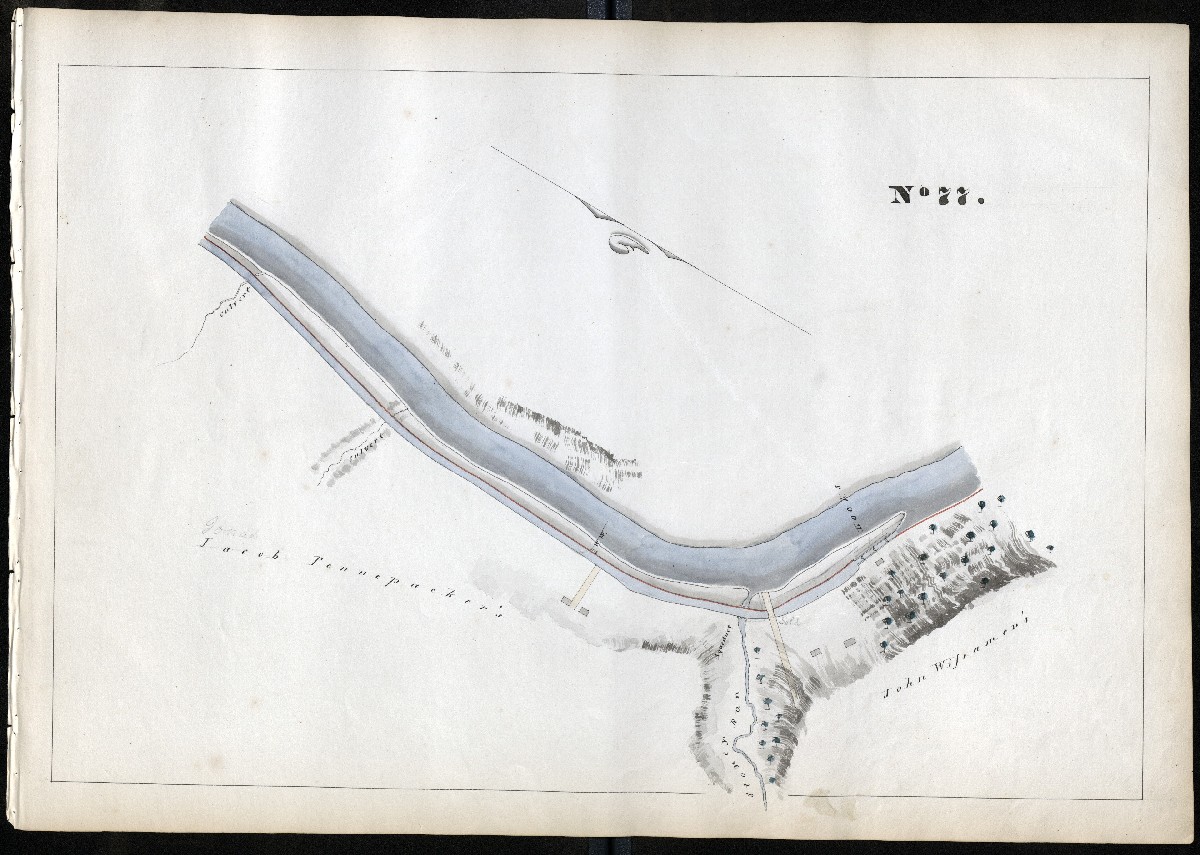

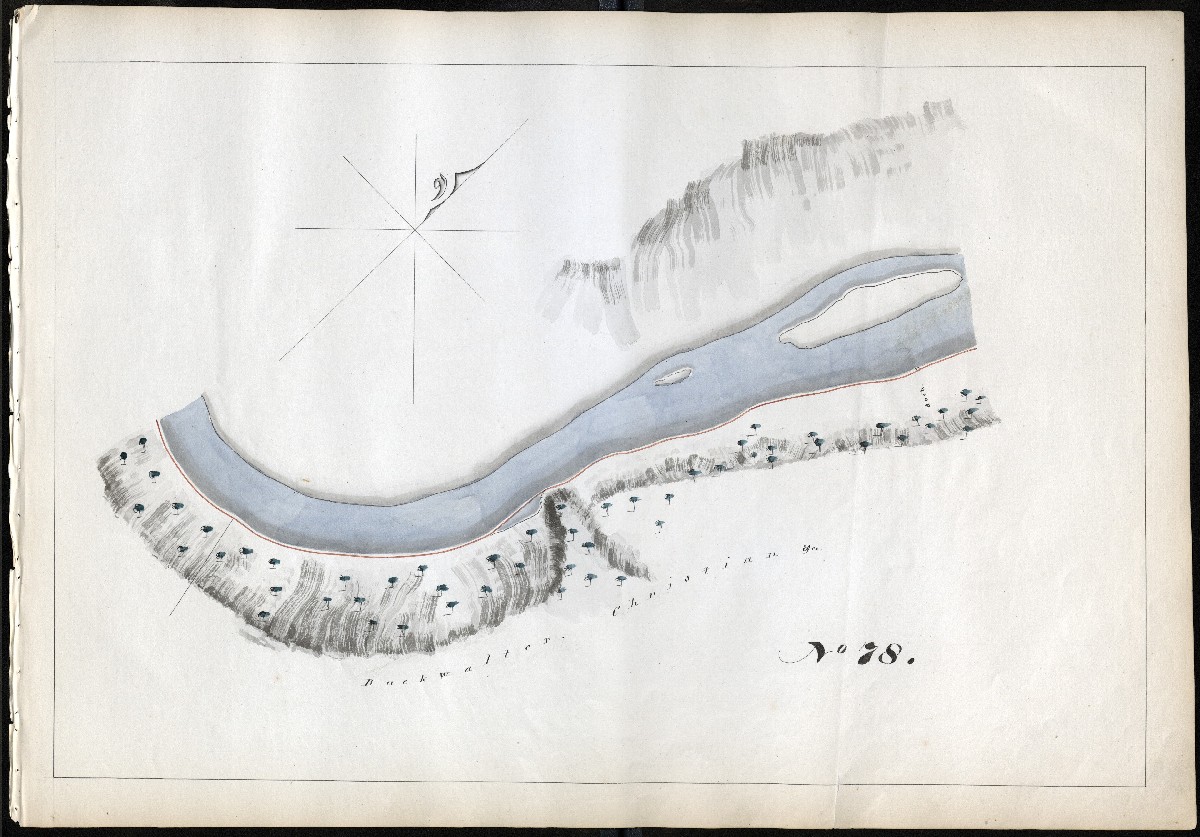

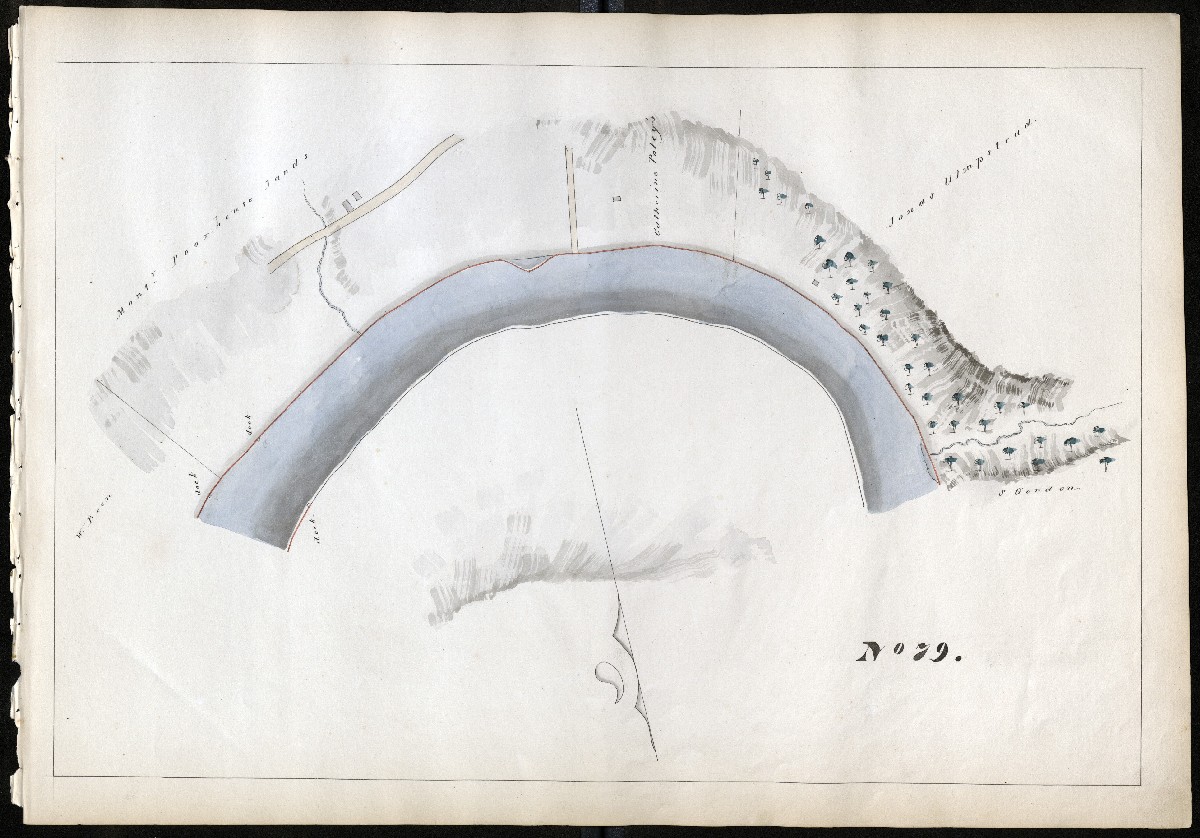

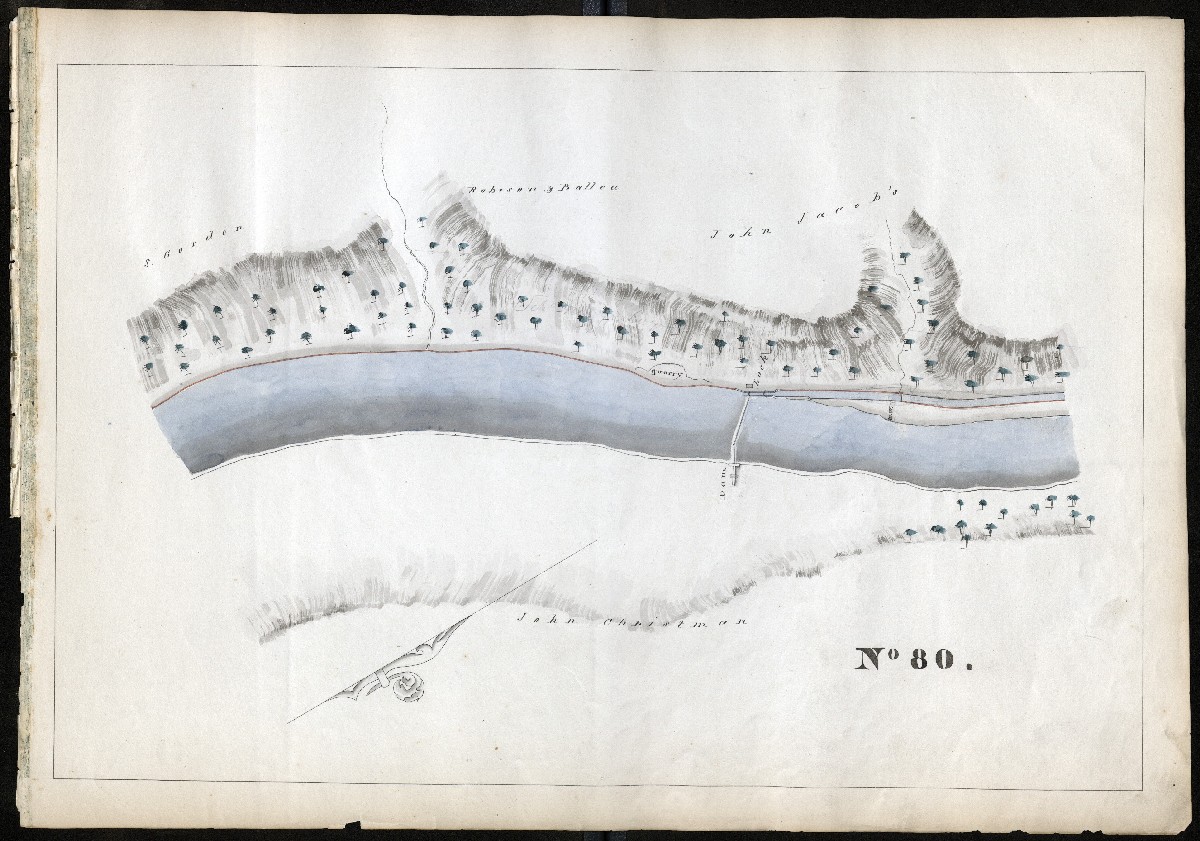

108 maps plus cover, hand drawn in gold, glue, green, lavender, yellow watercolor. With later annotations in pencil. Each page is 17.75″ x 25.” Field observation and map comparisons find that Gill’s survey was remarkably accurate for its time. The images presented are about half the size and reduced in quality from the original scans.

SOURCE

In 2021, the Philadelphia Water Department’s education arm, the Fairmount Water Works, supported high-resolution scans of all 108 pages of this beautiful oversized map book. It was created in 1827 by Thomas H. Gill for the private Philadelphia-based Schuylkill Navigation Company (SNC). The original (and what we believe is the only) copy is housed at the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, as part of Manuscript Group MG-110, Schuylkill Navigation Company Records, 1815-1951.

Introduction to the Maps

by Sandy Sorlien, author, Inland

The information contained in these 108 maps has been invaluable to our understanding of the Schuylkill Navigation, often known as the Schuylkill Canal. This book, along with later maps and profiles of the system, clearly indicates that there were at least 27 separate canals, not just one long one. Rather, the Schuylkill Navigation was a slackwater-canal system, with almost half of the 108.23 miles of tamed waterway consisting of slackwater pools behind dams. Boats would travel in and out of canals and the river, in both directions. They primarily carried anthracite from Schuylkill County to Philadelphia, the first and longest manmade coal-carrying waterway in Pennsylvania. The official opening of the Navigation was May 20, 1825, several months before the Erie Canal was completed in New York.

Not much is discoverable about Thomas H. Gill. He was likely the brother of Schuylkill Navigation Company engineer Edward Gill. In 1833, Edward Gill drew a huge long map of the lower portion of the Navigation, to which an annotator added notes and crossouts in red, some after 1850. This map is also housed at the State Archives. Thomas, though, didn’t leave any obvious works after this Survey; he may have died young. A Thomas H. Gill died in Philadelphia in 1828, but it is uncertain if this is the same man who created these beautiful maps. If anyone has better genealogical research skills and can come up with more information, we would be happy to add it to this account.

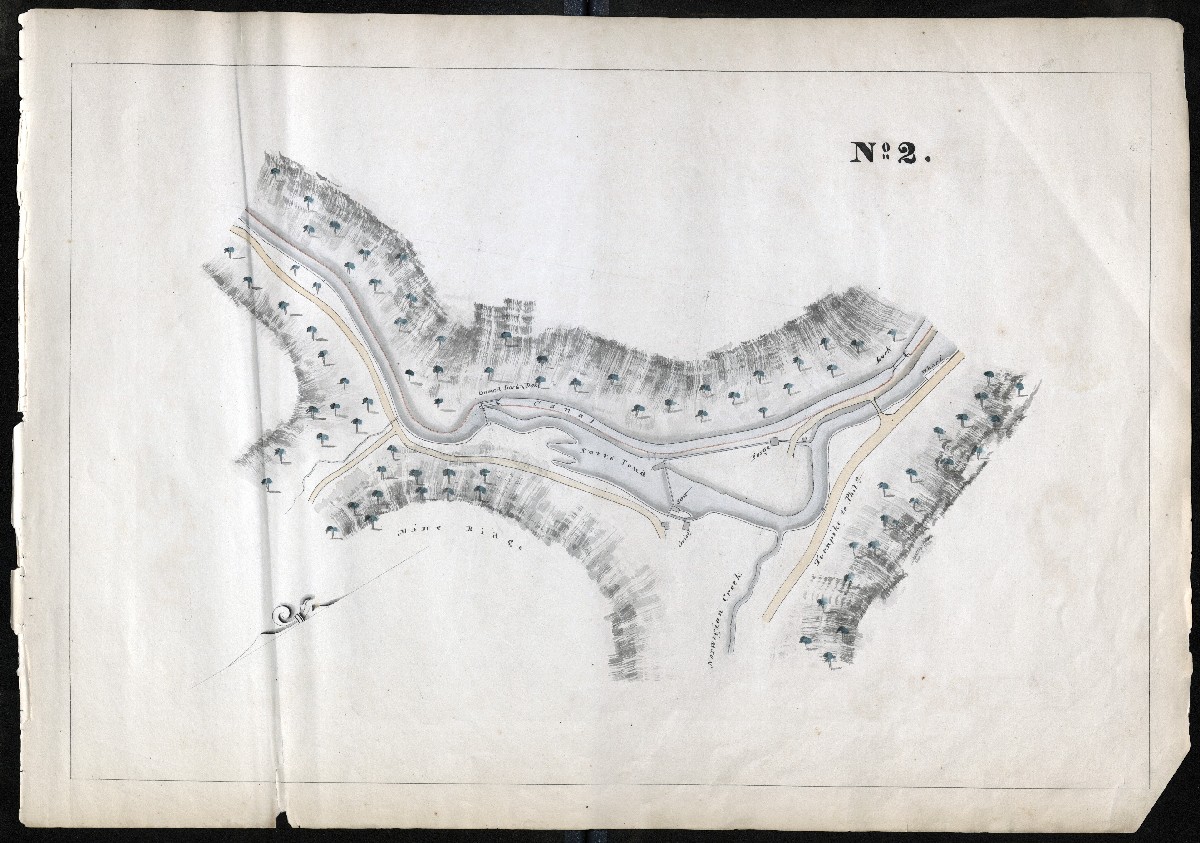

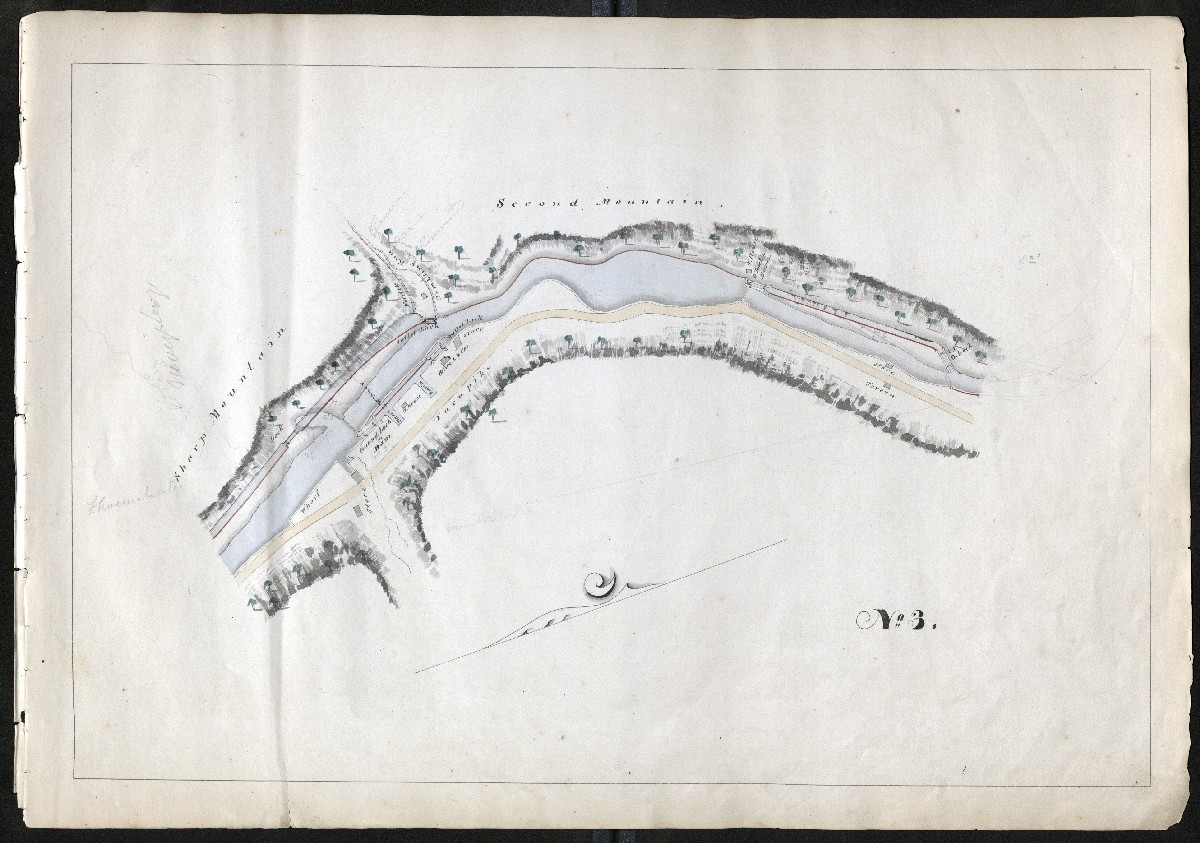

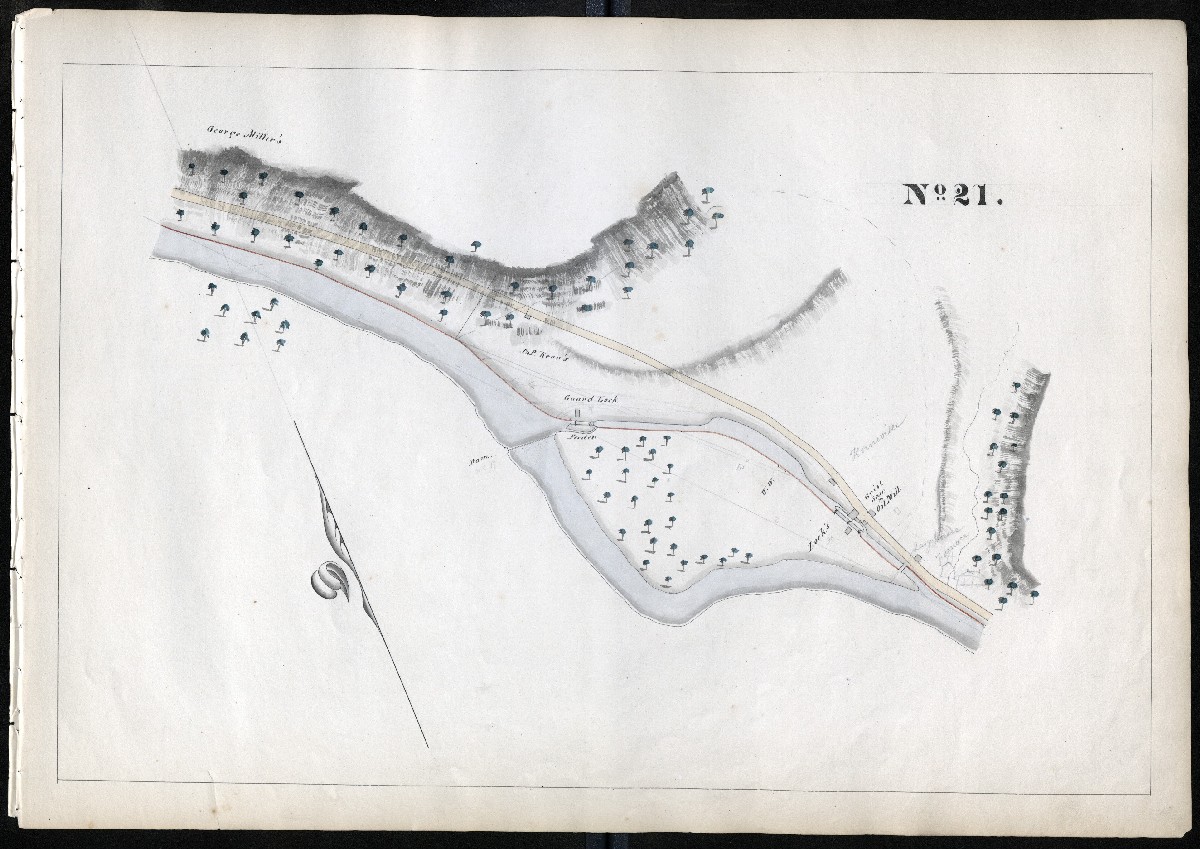

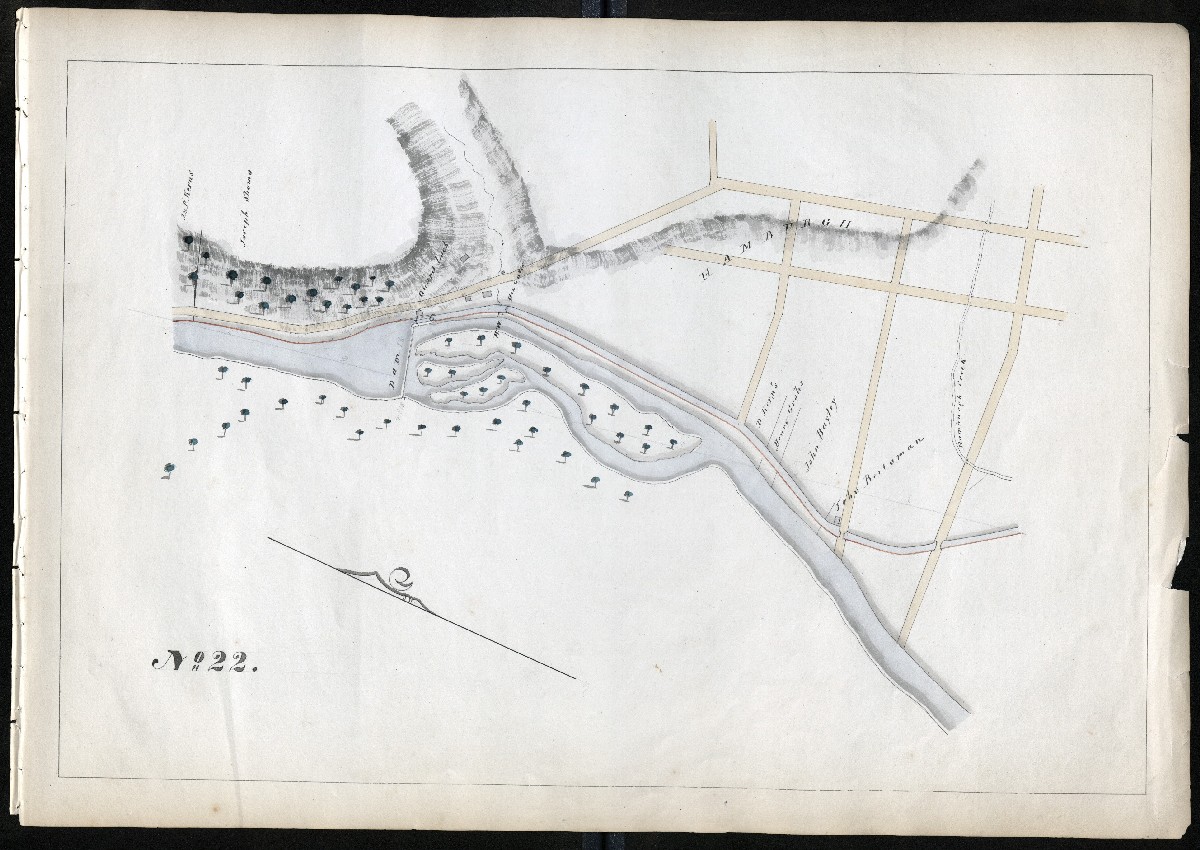

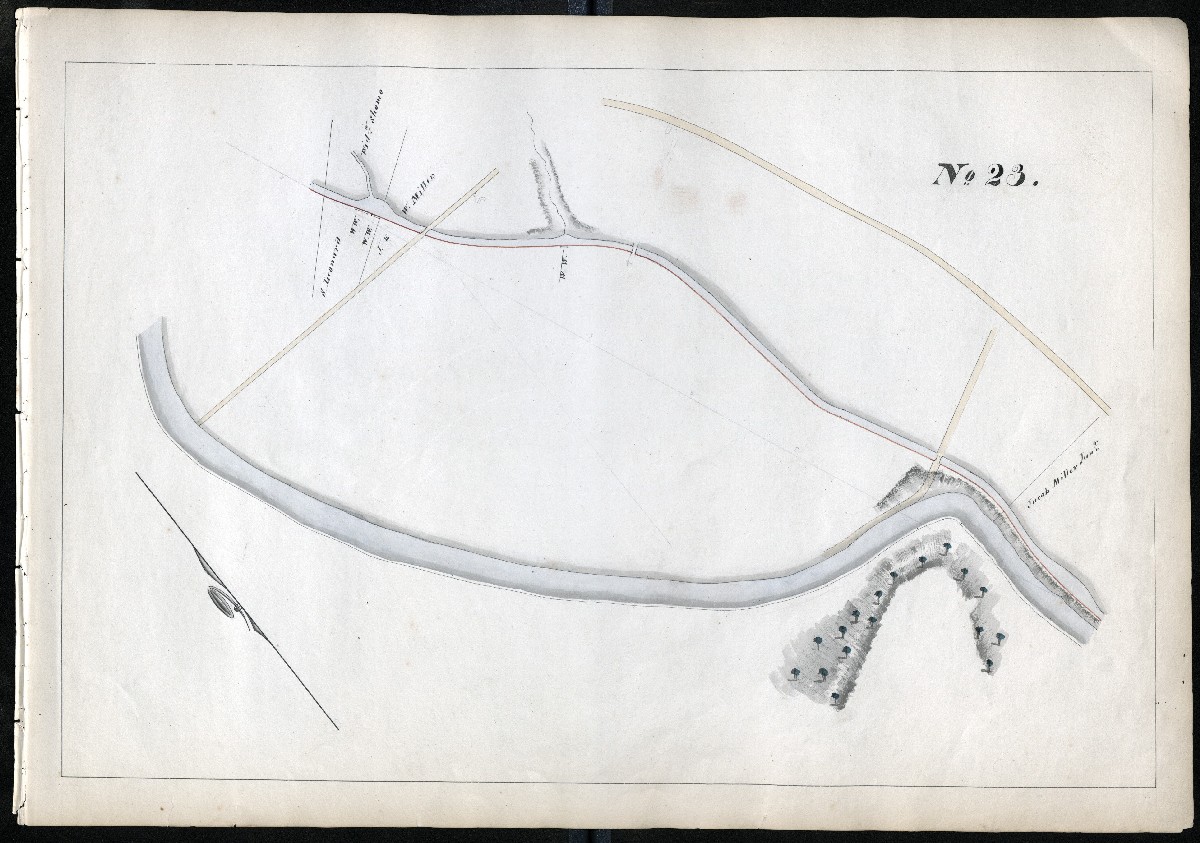

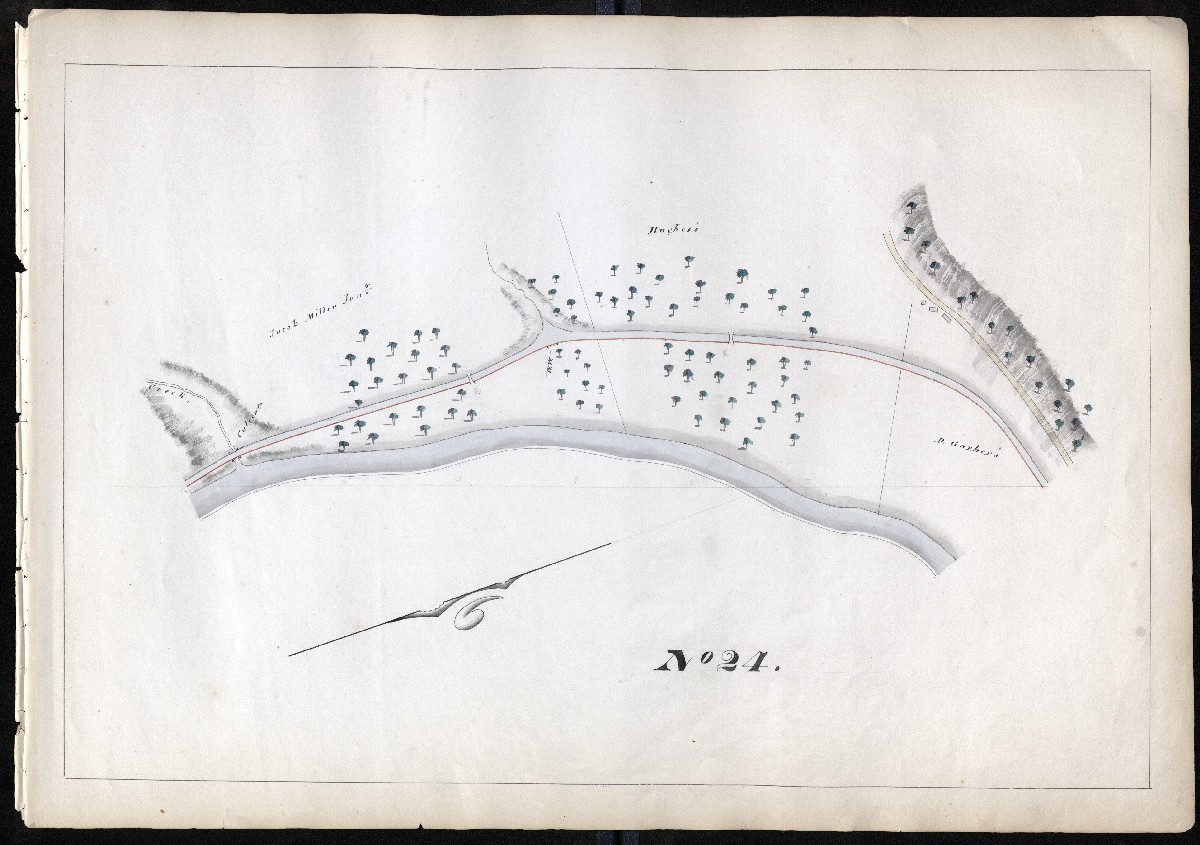

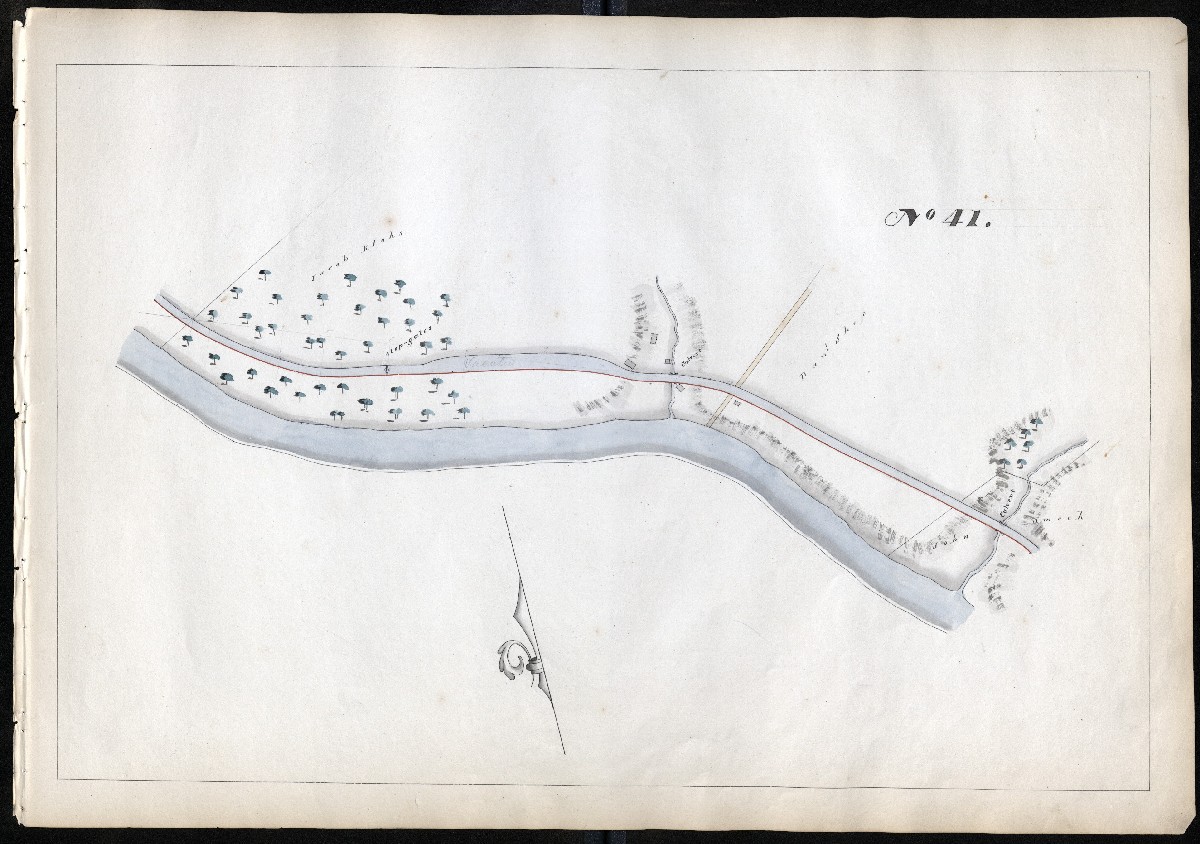

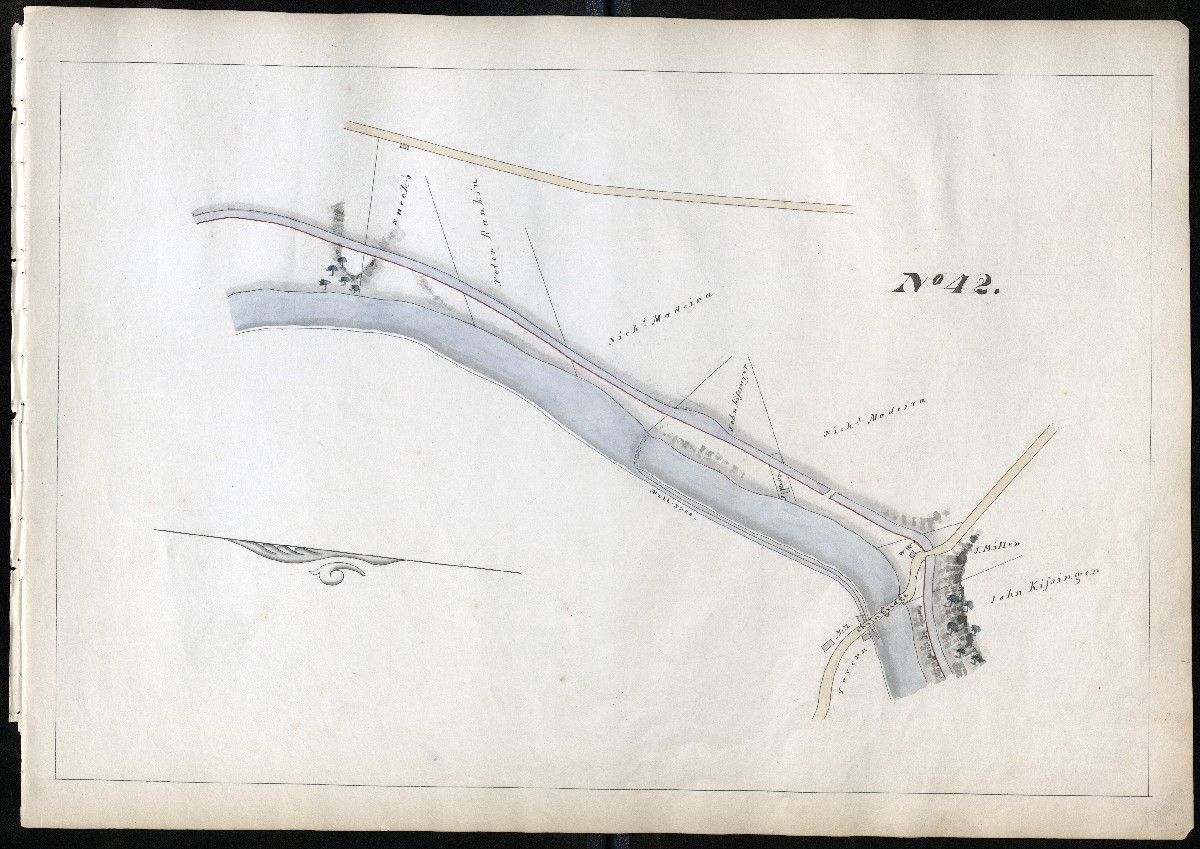

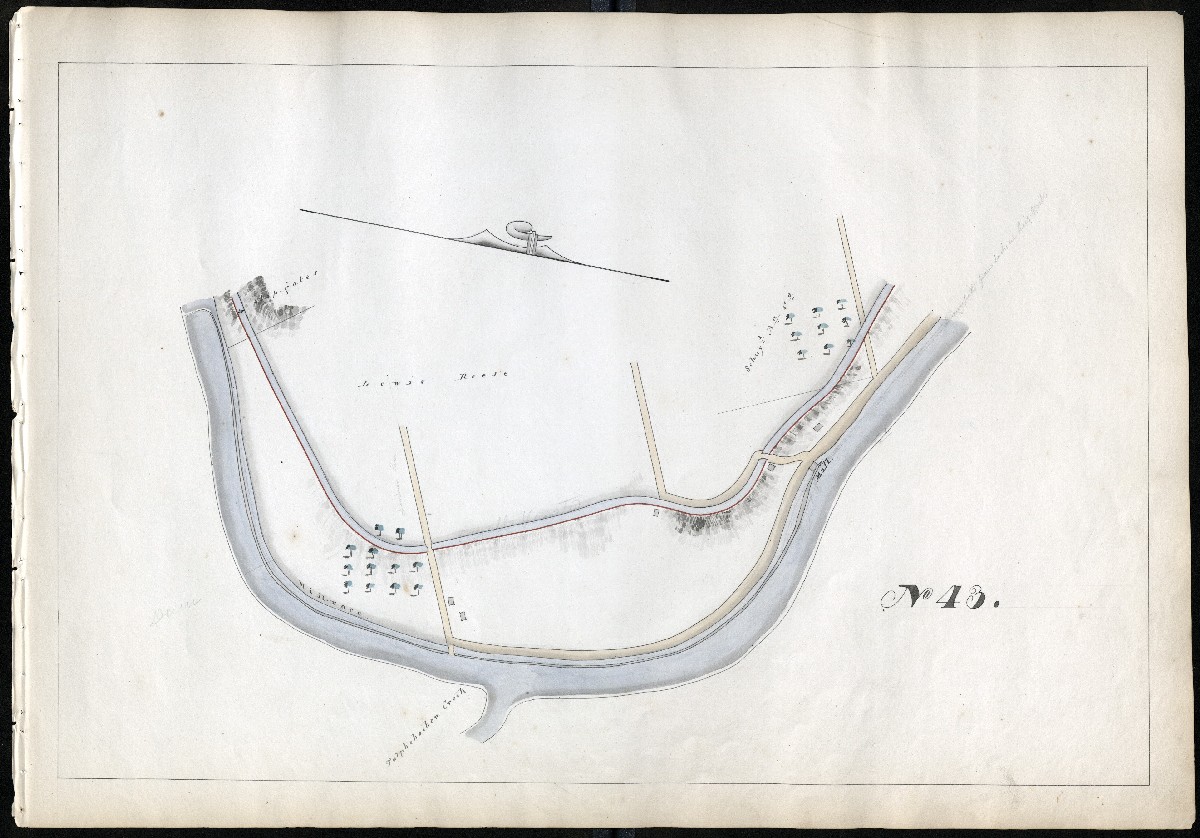

108 Maps – One for each mile

The Gill maps are numbered 1 to 108, one for each mile of the Navigation, starting at the upstream end of the system. Property owners’ names, tributaries, locks, dams, aqueducts, culverts, roads, bridges, and waste weirs (W.W.) are shown. Numerous buildings such as taverns and mills are labeled; some are not labeled. A building next to a lock was almost certainly the lock tender’s house, sometimes accompanied by a toll collector’s shack. Many of the towns in the Schuylkill Valley did not then exist. They were founded, or their footprints greatly expanded, by their canals and around specific locks, with smart entrepreneurs opening businesses to cater to the boatmen waiting their turn to “lock through.” The railroads along the Schuylkill River did not exist then, either.

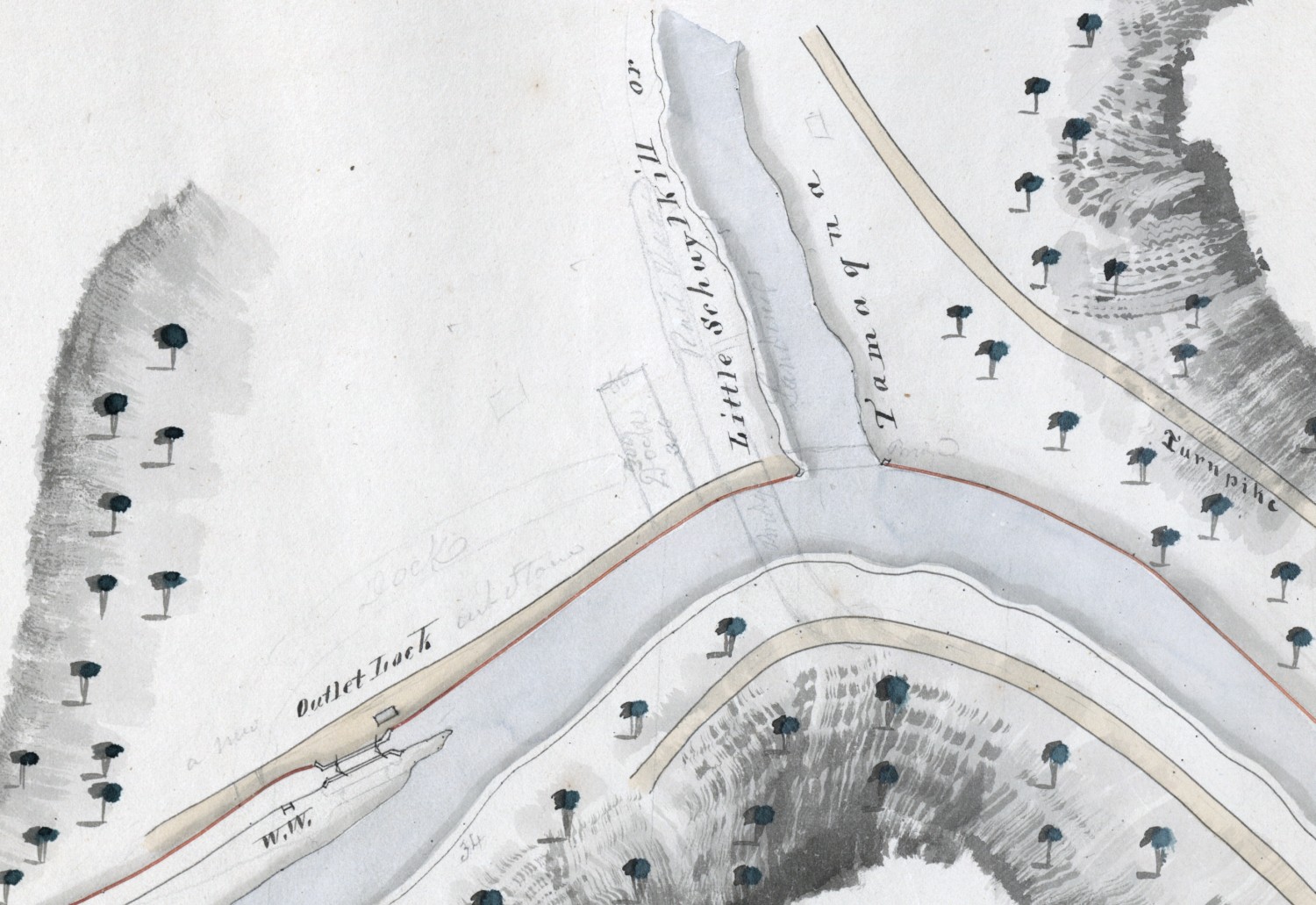

Towpath in red

On all 108 maps, the red line is the towpath or “towing path,” used by the mules that pulled the boats. The SNC towpaths were almost always between the canal and the river, where the land was flatter. The canal bank opposite the towpath was known as the “berme” or “berm” side. The towpaths also ran along the slackwater pools.

Later Annotations

The pencil annotations have provided a wealth of information about the evolution of the Navigation in its heyday. These notations came later, after the 1830s lock doubling, or after the 1846 system enlargement, or both. We have edited the original scans to increase the visibility of these sometimes-faint pencil marks. If you look closely, you can see new lock configurations and dam locations sketched in. The “V” of a lock’s miter gates always points upriver. Saving the JPEG and increasing contrast may help reveal details.

Lock numbering system

Combination locks are counted by how many consecutive chambers they have. The numbering system that appears on 1891 maps began in 1846 with the system enlargement, when channels were widened and deepened, allowing many locks to be eliminated and traffic to move much faster. A location with five locks (like “Five Locks” on Mile 25) was typically reduced to just two larger locks, and assigned two numbers. Two-lock combinations or combines were typically reduced to just one chamber. In some cases, though, the sketches were done to show lock doubling, a different process begun around 1830. That created side-by-side locks to allow simultaneous two-way traffic with shorter waiting times. Those were still too small to fit the 100-foot boats the SNC wanted to accommodate as demand for anthracite grew. When railways began competing for the coal trade, the enlargement was on. The new boats could carry up to 200 tons.

The canal names, lock names, and lock numbers cited in the following list mostly came after Gill’s 1827 book. The most established names and some alternates are used on this 1890s Profile by SNC Engineer Edwin Smith. The most enduring names were chosen for a new map by Morgan Pfaelzer for my 2022 book Inland. Alternate names may be found in this comprehensive index compiled by Larry Whyte. The post-1846 lock numbers (from Mount Carbon to Norristown only) are all found on these nine maps by Smith – the numbers without circles around them.

In 1846, locks were numbered 1-72. (Number 41 was skipped, at Felix Dam, where an intended second lock was probably never built.) Not all guard locks (“g.lock” on the Gill maps) next to the dams were assigned numbers; many were removed during the enlargement or became guard gates with no lift. All outlet locks had lift, and were given numbers.

Thomas Gill did not note any lock or dam numbers, not even an early numbering system found on engineering drawings of the 1840s. Fortunately, the anonymous pencil annotator(s) did add some post-1846 numbers. In the list below, we provide them to help orient readers in relation to later maps and current on-site signage.

Click links to jump to maps for each county:

Schuylkill, Berks, Chester, Montgomery, Philadelphia

Schuylkill County, Miles 1 – 19

MILE 1

Head of Navigation, Mill Creek at Port Carbon, Lock 1 and Dam 1 (opened 1828, lock and docks abandoned due to siltation in 1853). The Lenni Lenape name “MANAIUNK” appears along with the Dutch SCHUYLKILL for the name of the river. About 100 miles below, we will come to Manayunk: see Maps 100-103.

MILE 2

Greenwood Canal, Lock 2 and Lock 3 on the Palo Alto side of the river, across from Pottsville. Dam 2 provided the pool for the Firth Docks built later after Dam 1 and Lock 1 were taken out of service in 1853. “Turnpike to Phila.” is shown – the 1808 Centre Turnpike that ended at Reading and largely became Route 61.

MILE 3

Mount Carbon, the Head of Navigation from 1821 to 1828 before the upper 2.5 miles were completed to Port Carbon. The outlet lock of the Greenwood Canal became Lock 5, preceded by Lock 4. Tumbling Run (shown) by the 1830s had two reservoirs to supply water to the Navigation. A short canal on river left known as the Mount Carbon Level included Lock 6.

MILE 4

Second Mountain Canal, Dam 5, Locks 7 and 8.

MILE 5

Waterloo Canal heading to Schuylkill Haven, Dam 6 and Guard Lock 9 passes Seven Stars Hotel to Locks 10/11, then known as “Five Locks” (as other five-chamber flights were) and other names

MILE 6

Waterloo Canal, shows end of Five Locks where five chambers became two at Connor’s Crossing Locks 10/11, confluence of West Branch of the Schuylkill near a lock later removed, then Outlet Lock 12 Bausman’s, into Dam 7 in Schuylkill Haven

MILE 7

Haven Canal, later Canal Street and now Parkway in Schuylkill Haven, Guard Lock 13, Lock 14

MILE 8

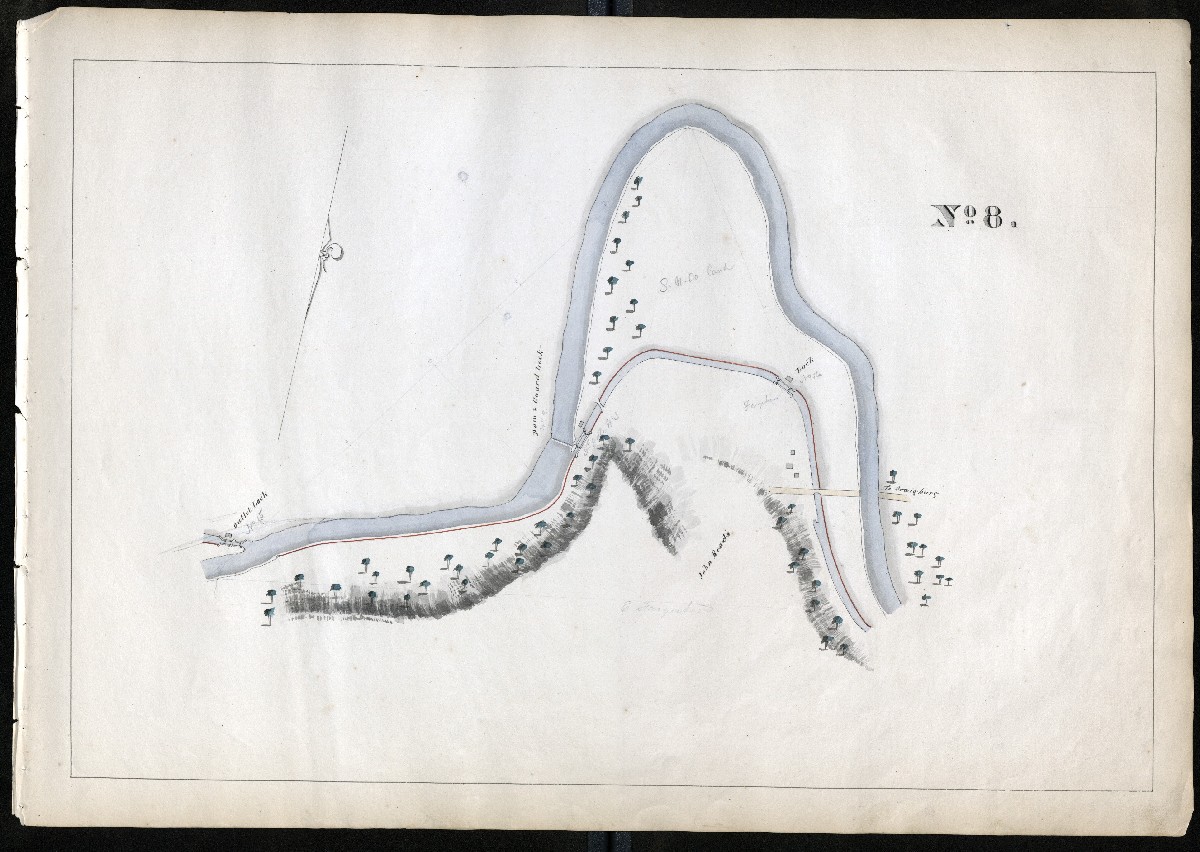

Haven Canal, Outlet Lock 15, ford or ferry to river right and Dam 8 Bowen’s, unnumbered guard lock to Lock 16, Farquahar’s Canal. The course of the river oxbow here has since changed.

MILE 9

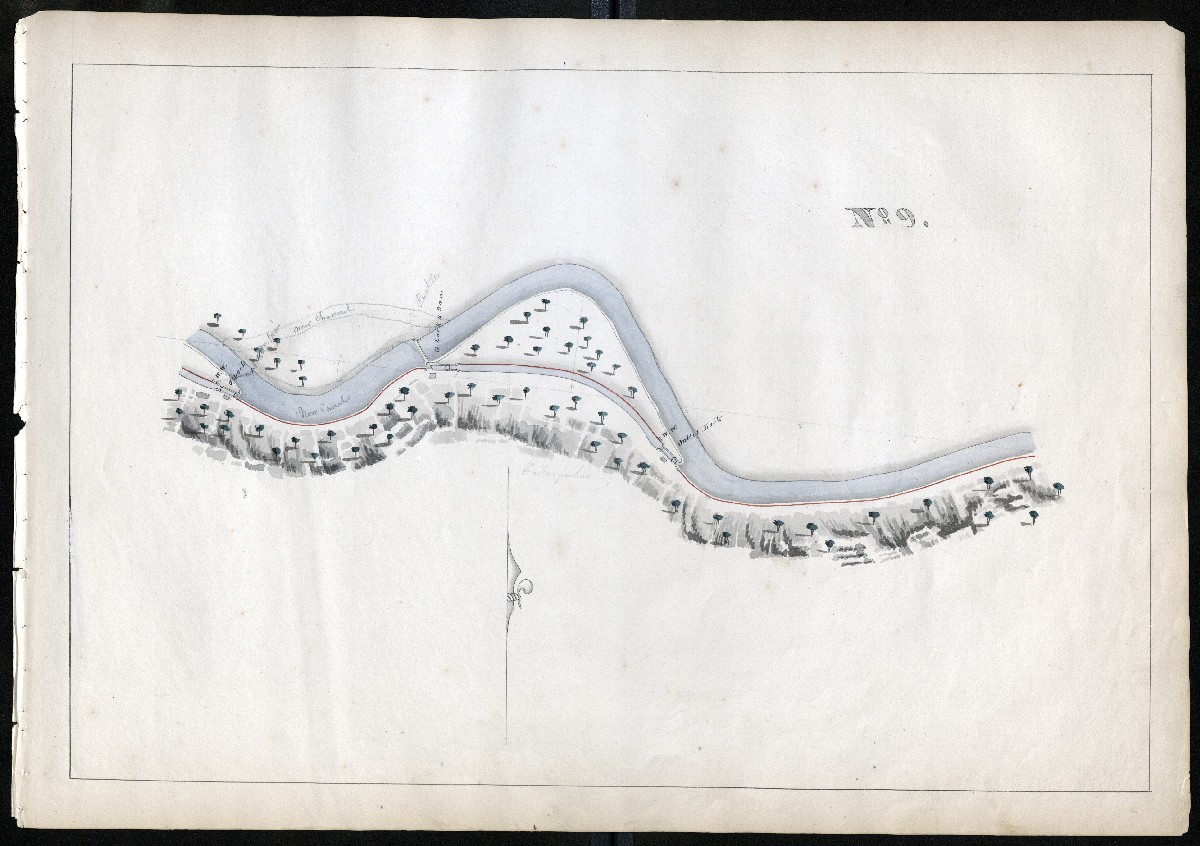

Farquahar’s Canal, Outlet Lock 17, followed by a short canal later eliminated. Pencil sketch indicates where new channel was cut to bypass that canal.

MILE 10

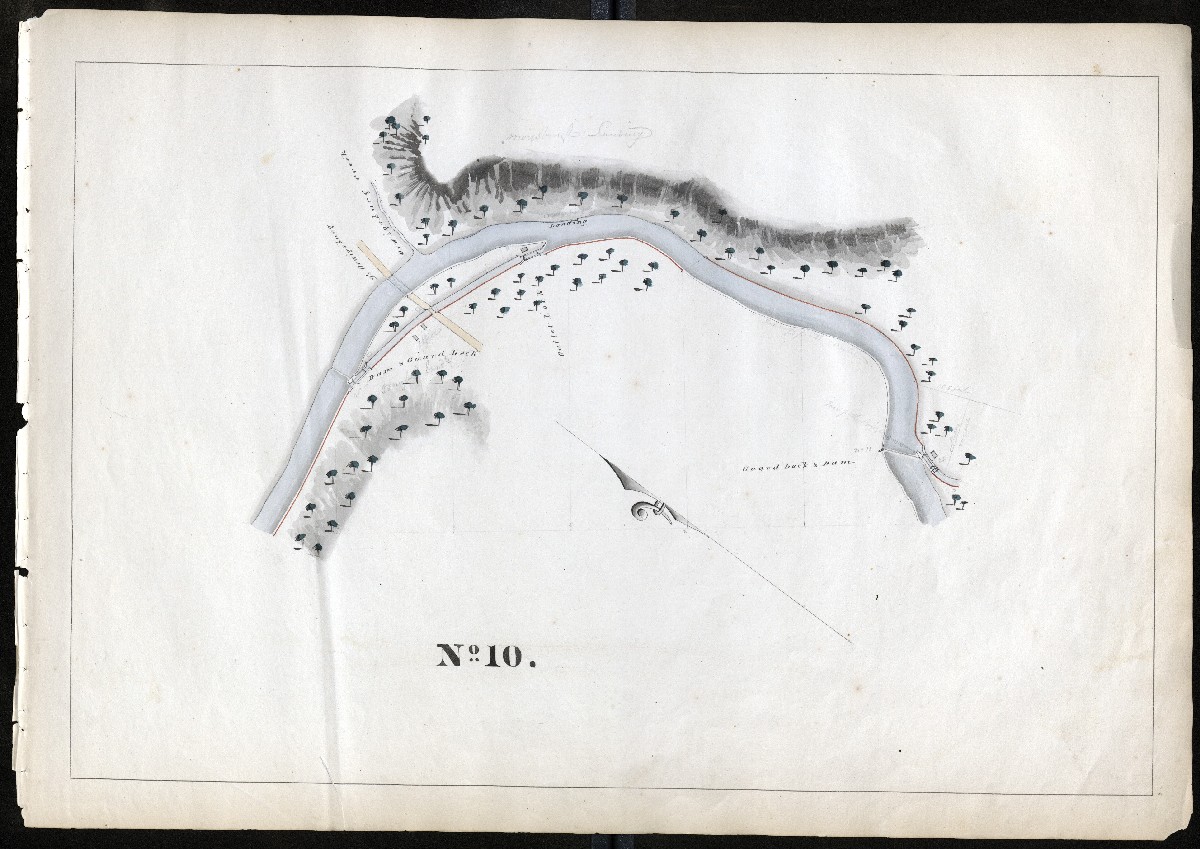

Orwigsburg Landing, now Landingville, Outlet Lock 18 from short canal into Dam 10 and Guard Lock 19 to Tunnel Canal

MILE 11

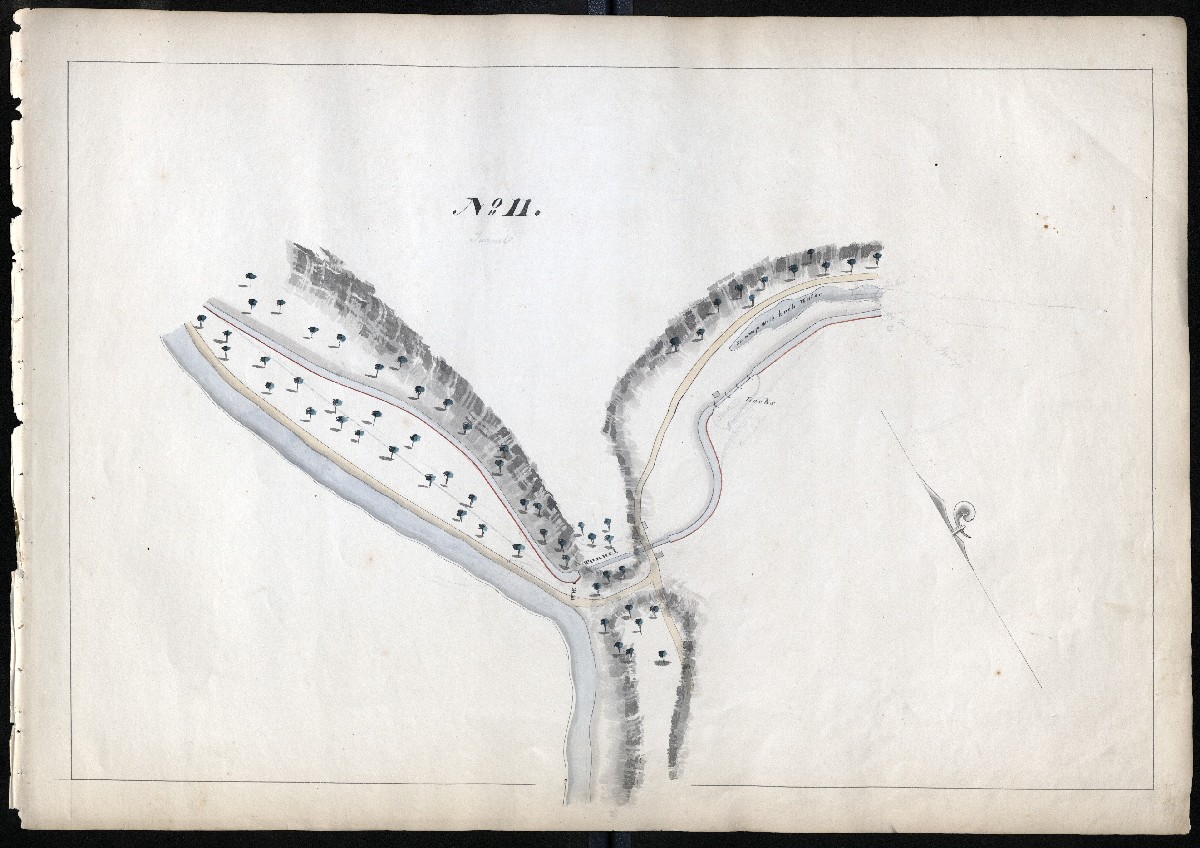

The “Upper Level” of the Tunnel Canal (now much wider Landingville Marsh) through the Auburn Tunnel, which opened 1821 as first transportation tunnel in America, 450 feet long. Daylighted in the 1850s. Lock 20, three chambers to become a single lock, and a boat basin

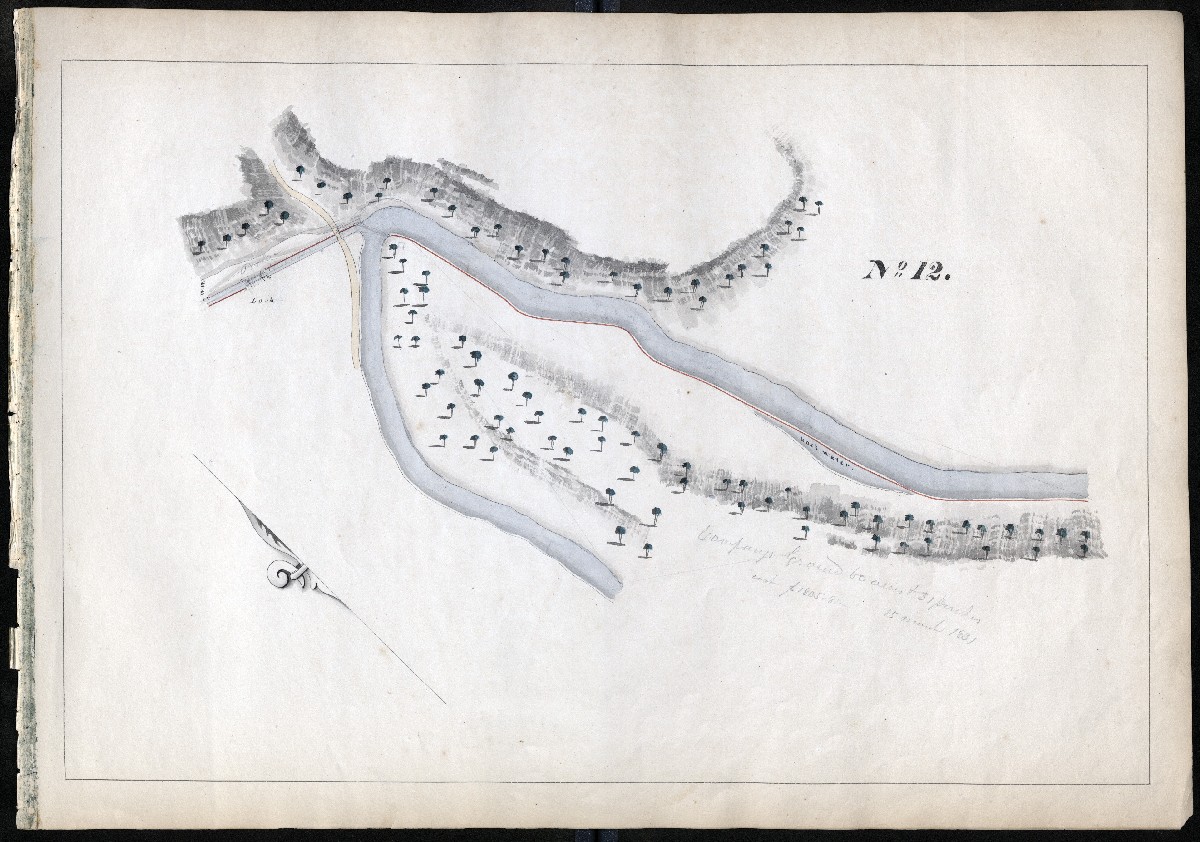

MILE 12

Tunnel Canal Outlet Lock 21, location moved after the course of the river oxbow here was changed

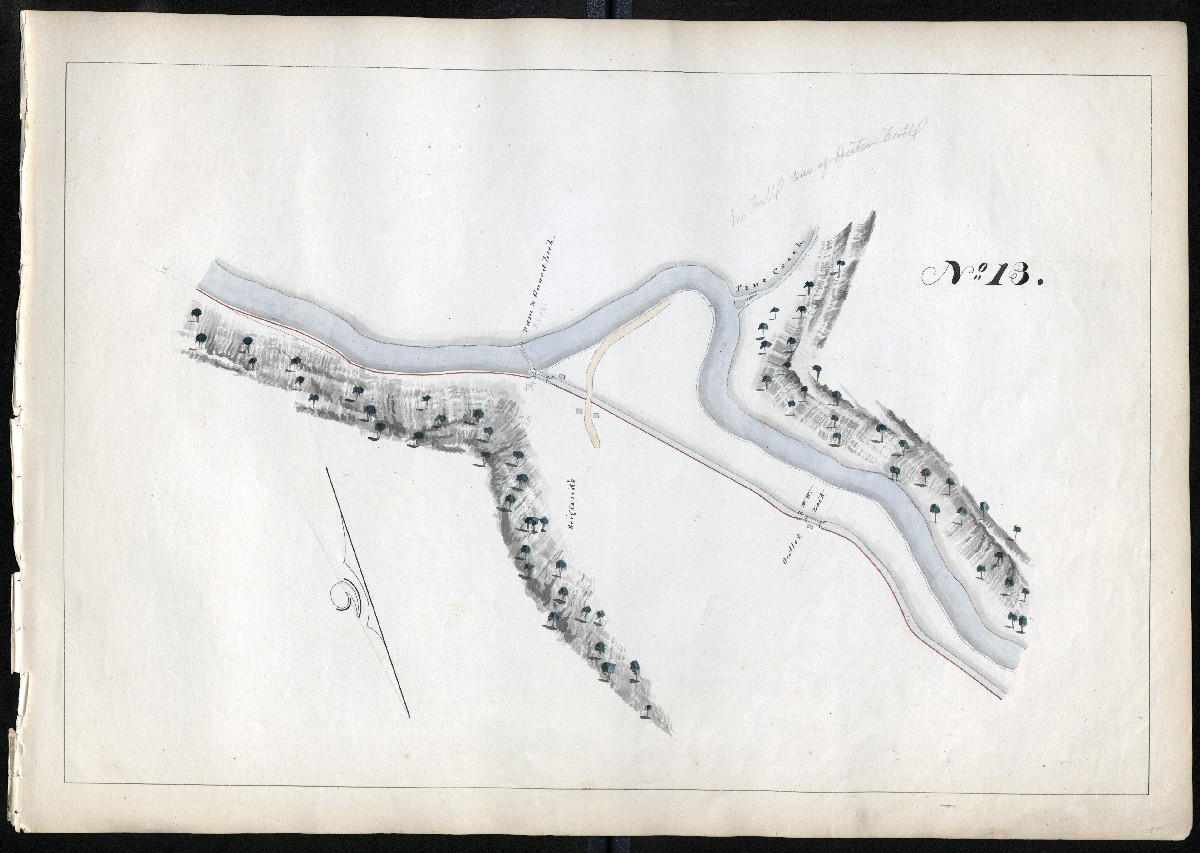

MILE 13

Dam 12, guard lock, and Scotchman’s Canal and Outlet Lock 22, Auburn

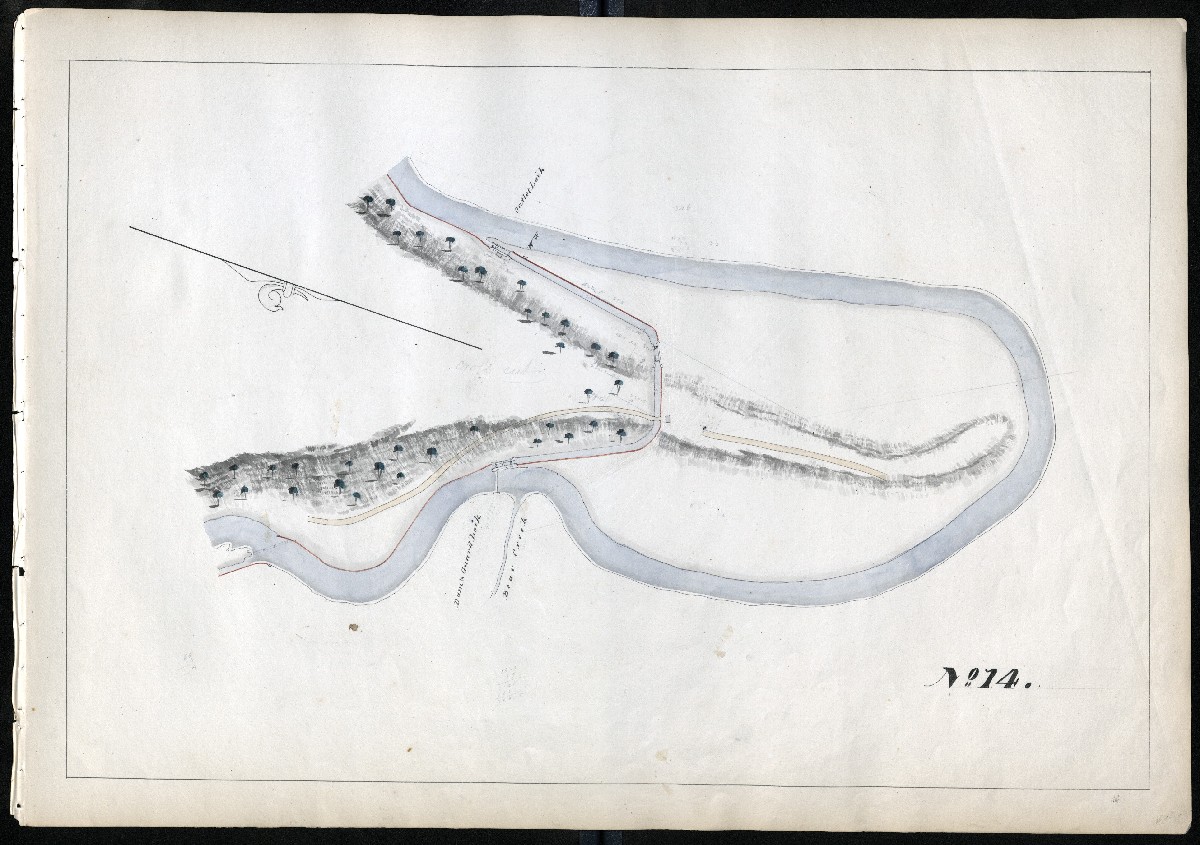

MILE 14

Dam 13, guard lock, and Crosscut Canal to “Log Cabin” Outlet Lock 23. Current site of new Auburn Bridge of the Bartram Tail/SRT. River Road, Bear Creek

MILE 15

Pool of Lord’s Dam 14

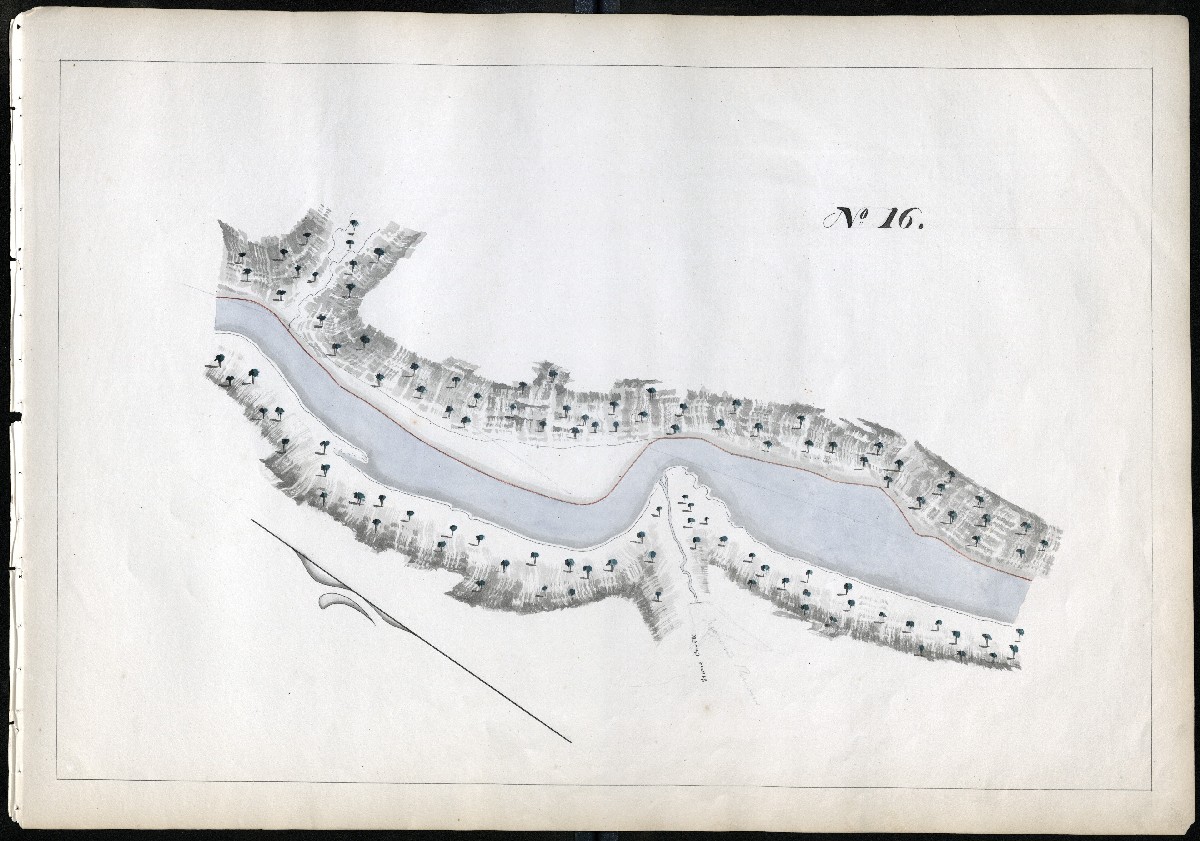

MILE 16

Pool of Lord’s Dam 14, Stone Creek or Stoney Creek

MILE 17

Tom Lord’s Dam and Canal, Guard Lock 24 to unnumbered lock and Outlet Lock 25, known as Rishel’s/Rischel’s

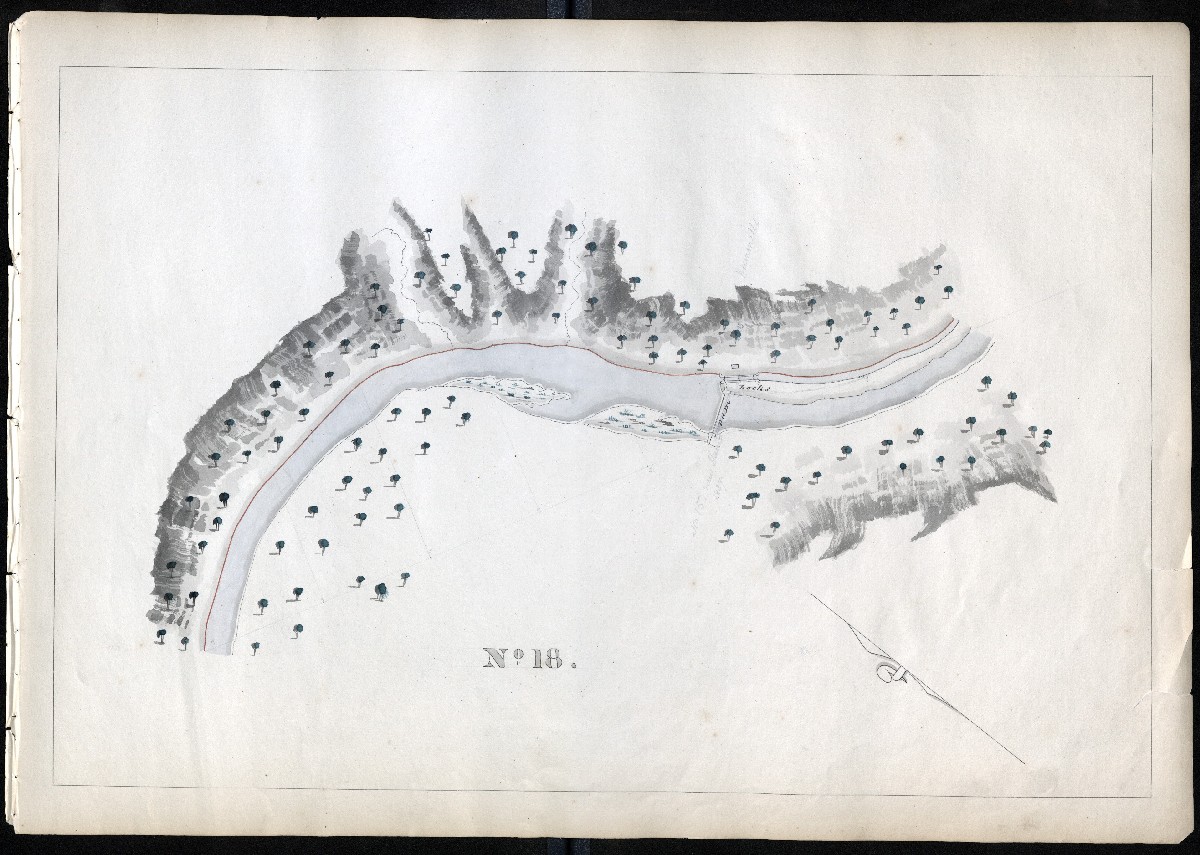

MILE 18

Hummel’s Dam 15, Guard Lock 26, Hummel’s Canal

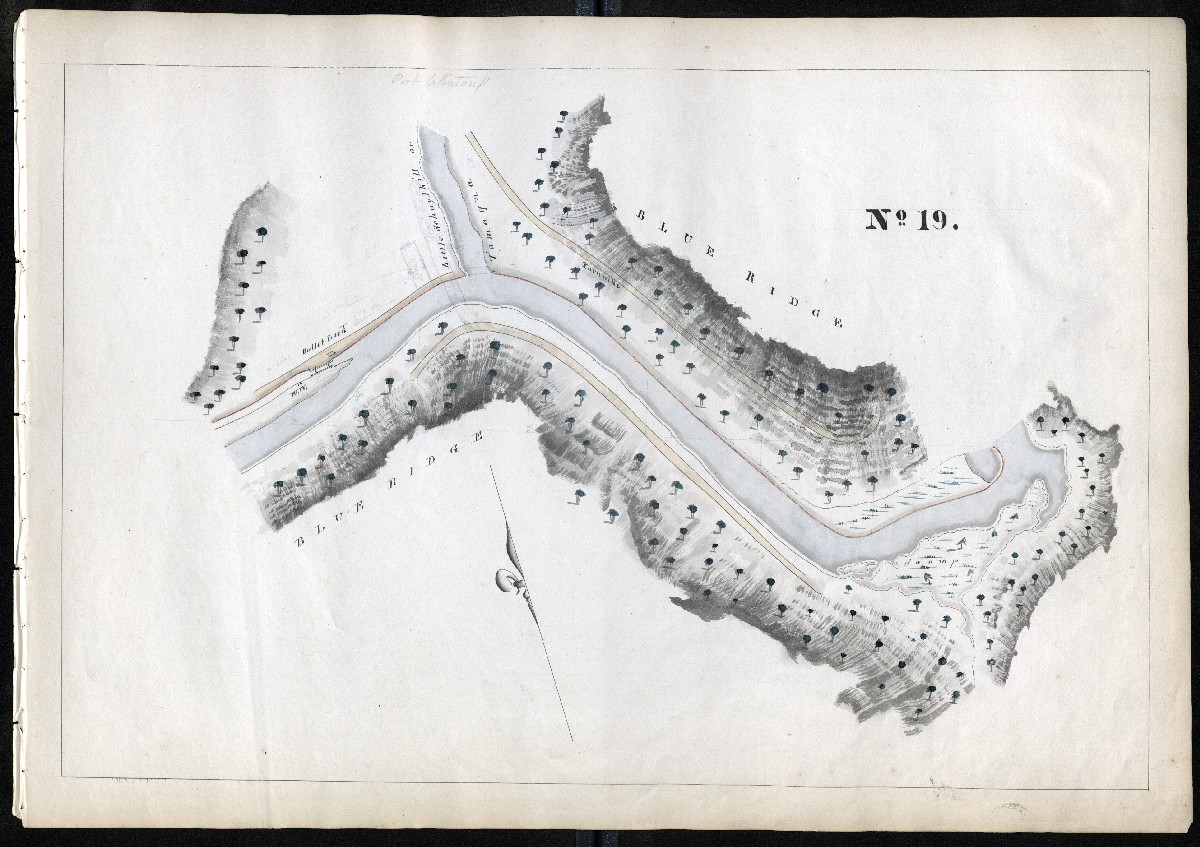

MILE 19

Outlet Lock 27, Port Clinton, confluence of Little Schuylkill River, also shown as Tamaqua River. Pencil sketch of coal loading docks.

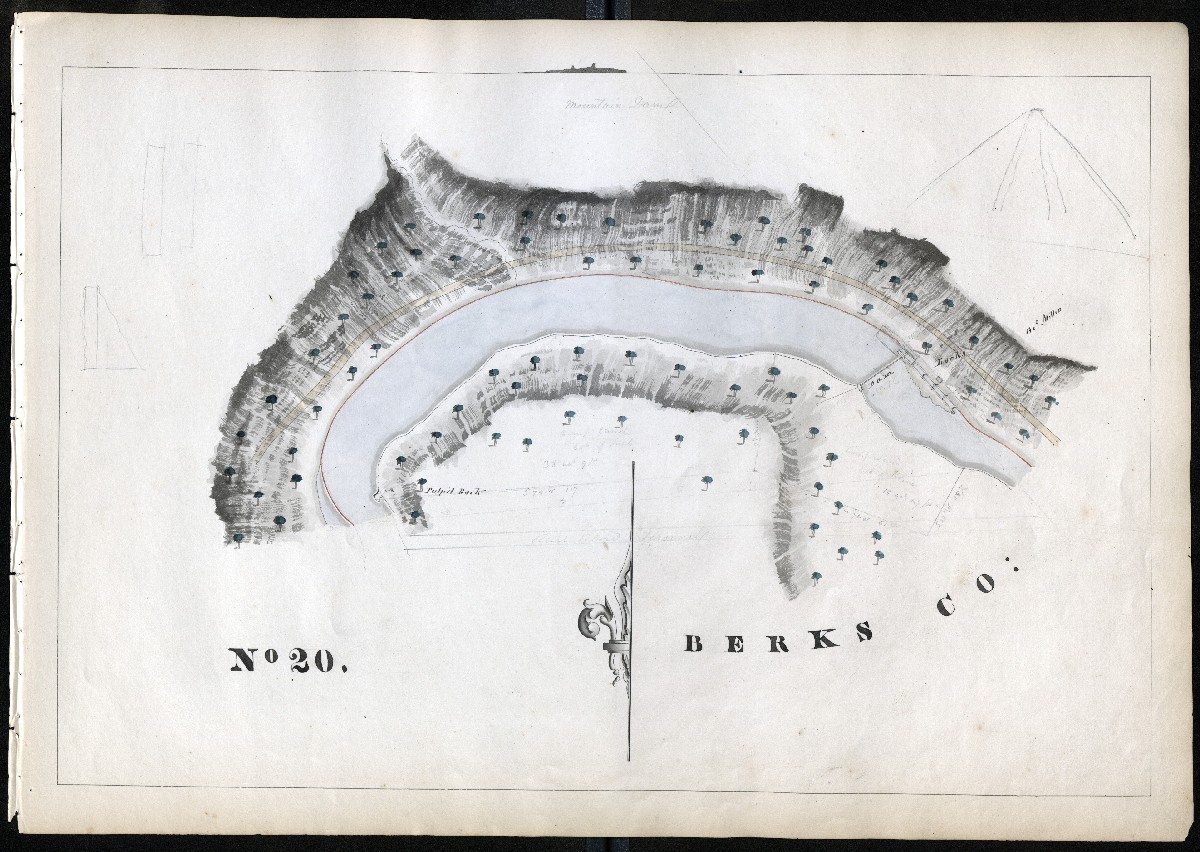

Berks County, Miles 20 – 62

MILE 20

Blue Mountain Dam 16 and locks. Five chambers in 1827 became two chambers Locks 28/29 after 1846 enlargement. Pulpit Rock far left.

MILE 21

MILE 22

Kernsville Dam 17 and Guard Lock to 10-mile Hamburg Canal, boat basin at Kernsville, two chamber lock became one, Lock 30 after 1846 enlargement. Town of Hamburgh/Hamburg

MILE 23

Hamburg Canal between Lock 30 and Locks 31/32

MILE 24

Hamburg Canal between Lock 30 and Locks 31/32

MILE 25

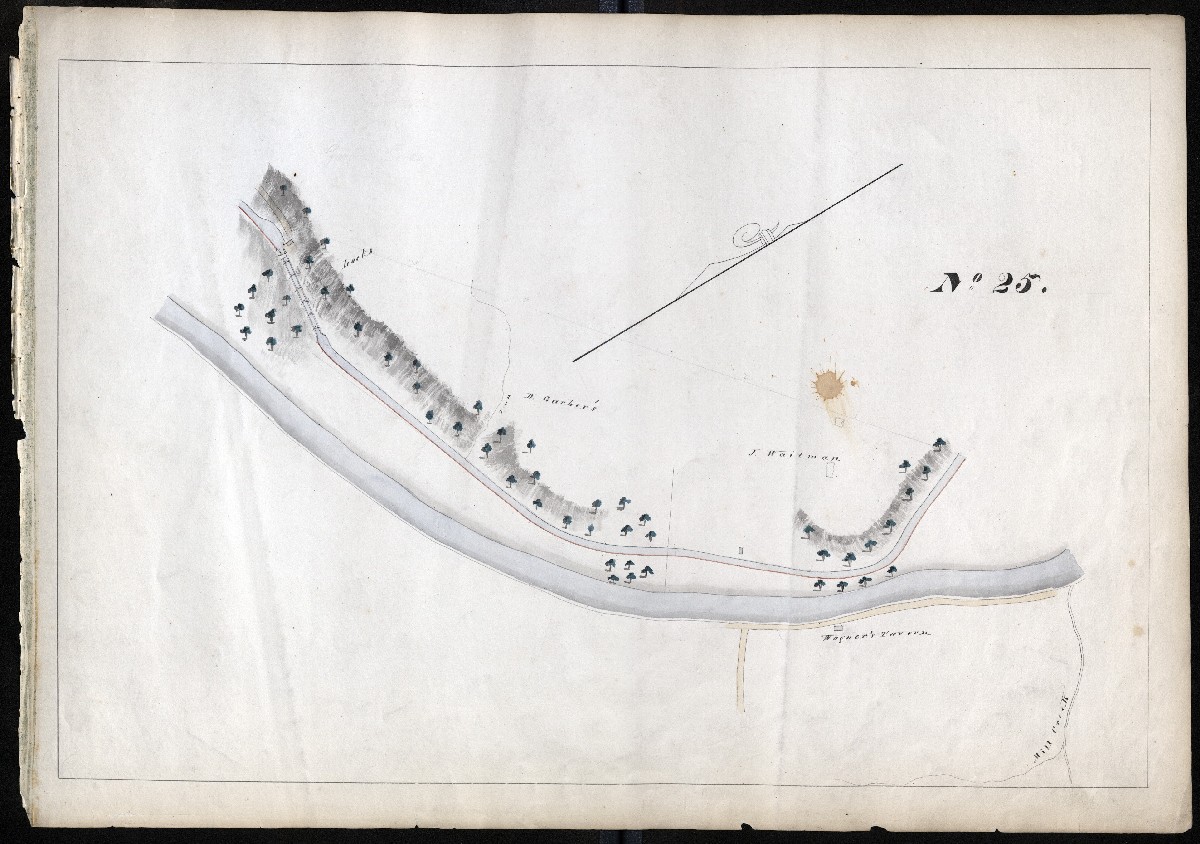

Hamburg Canal. Garber’s Five Locks became two chambers, Locks 31/32, after 1846 enlargement. Wagner’s Tavern

MILE 26

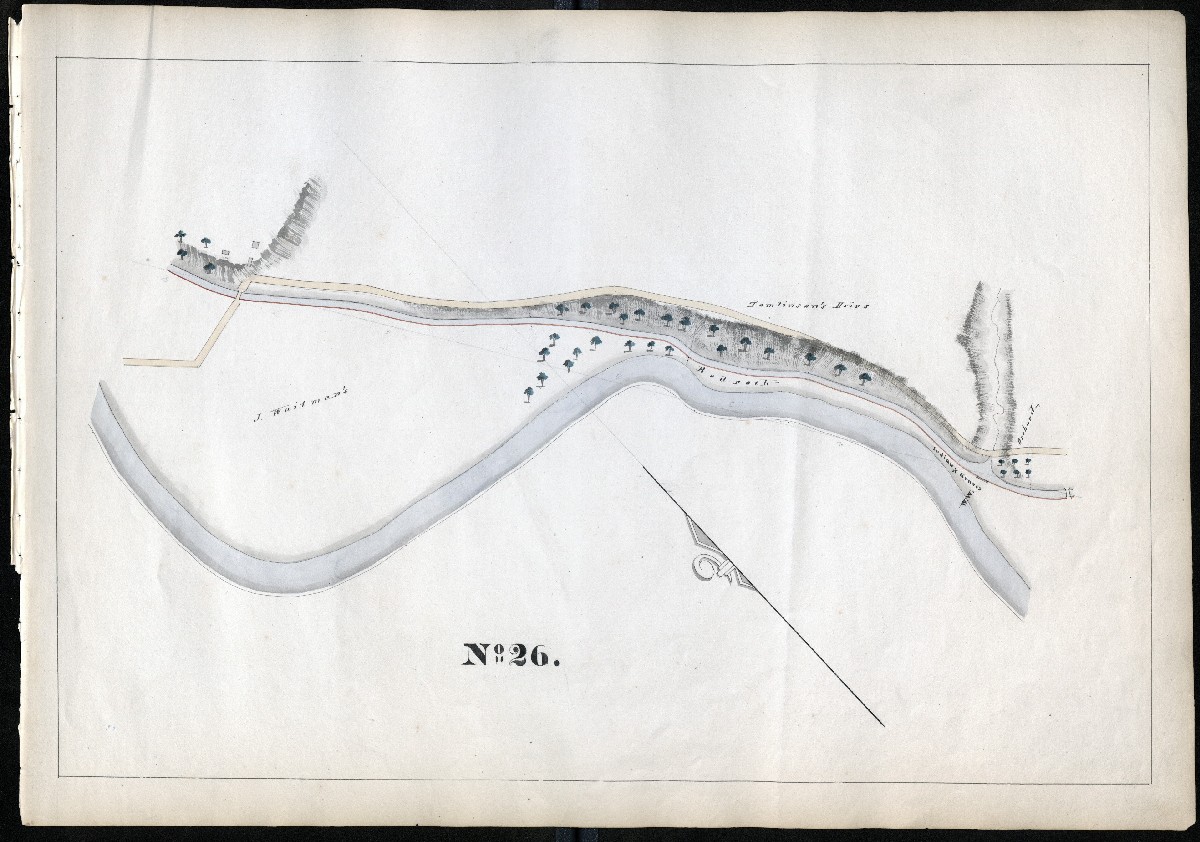

Hamburg Canal between Locks 31/32 and Lock 33 Shoemakersville

MILE 27

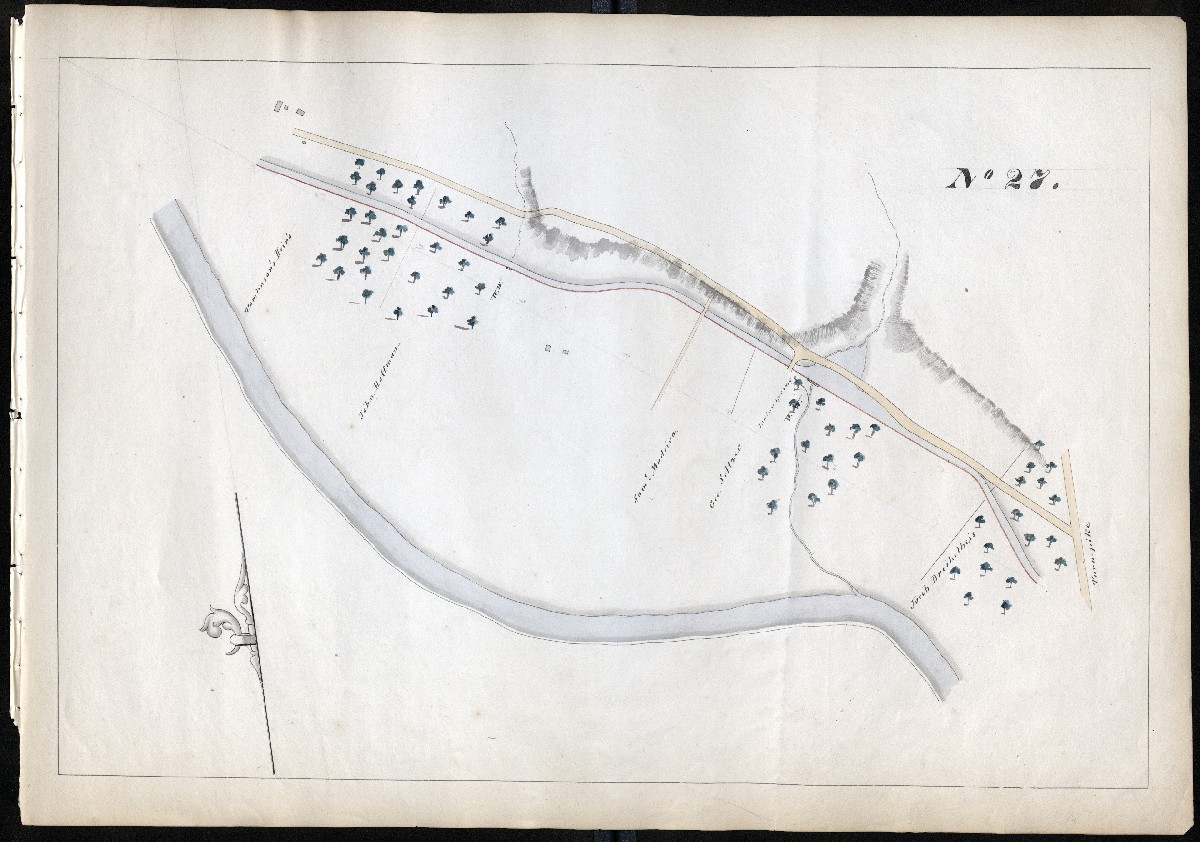

Hamburg Canal between Locks 31/32 and Lock 33 Shoemakersville

MILE 28

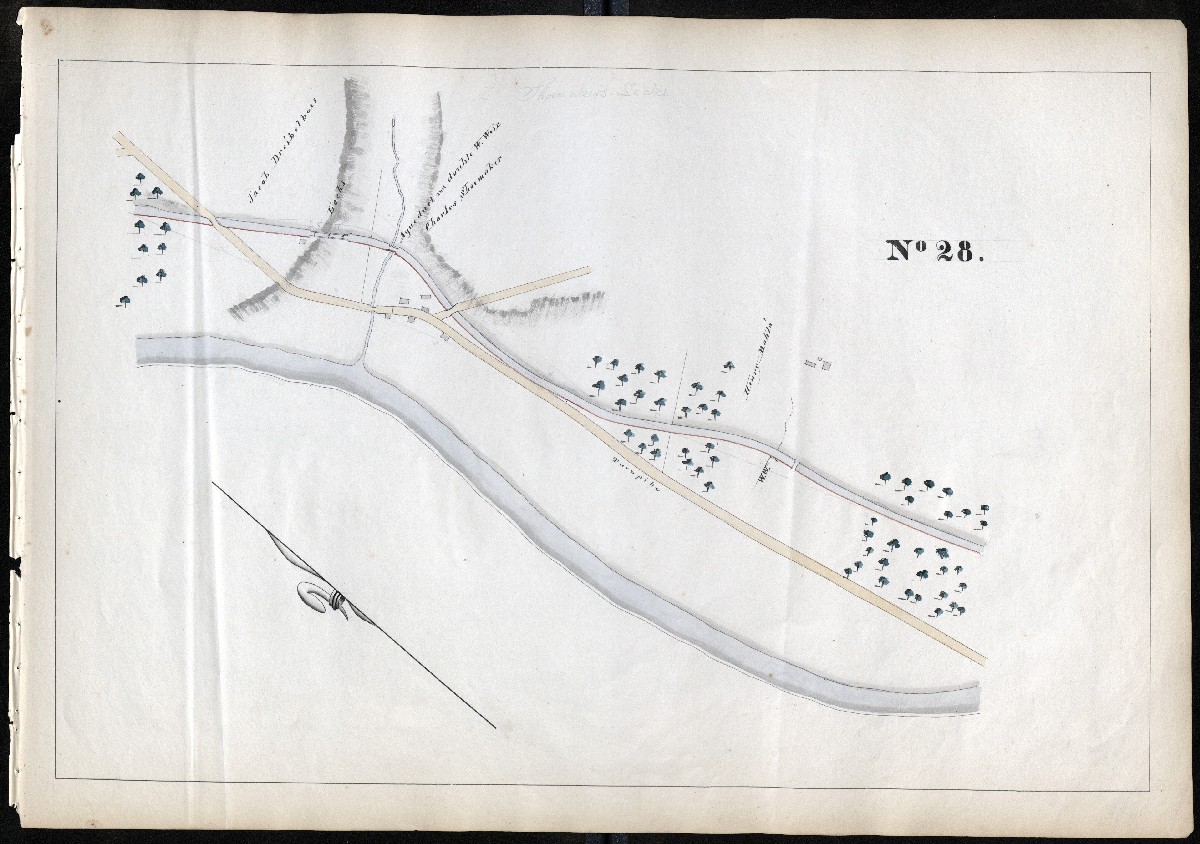

Hamburg Canal, two chamber lock became one, Lock 33, after 1846 enlargement. Pigeon Creek Aqueduct and double waste weir (There is another Pigeon Creek Aqueduct in Chester County.)

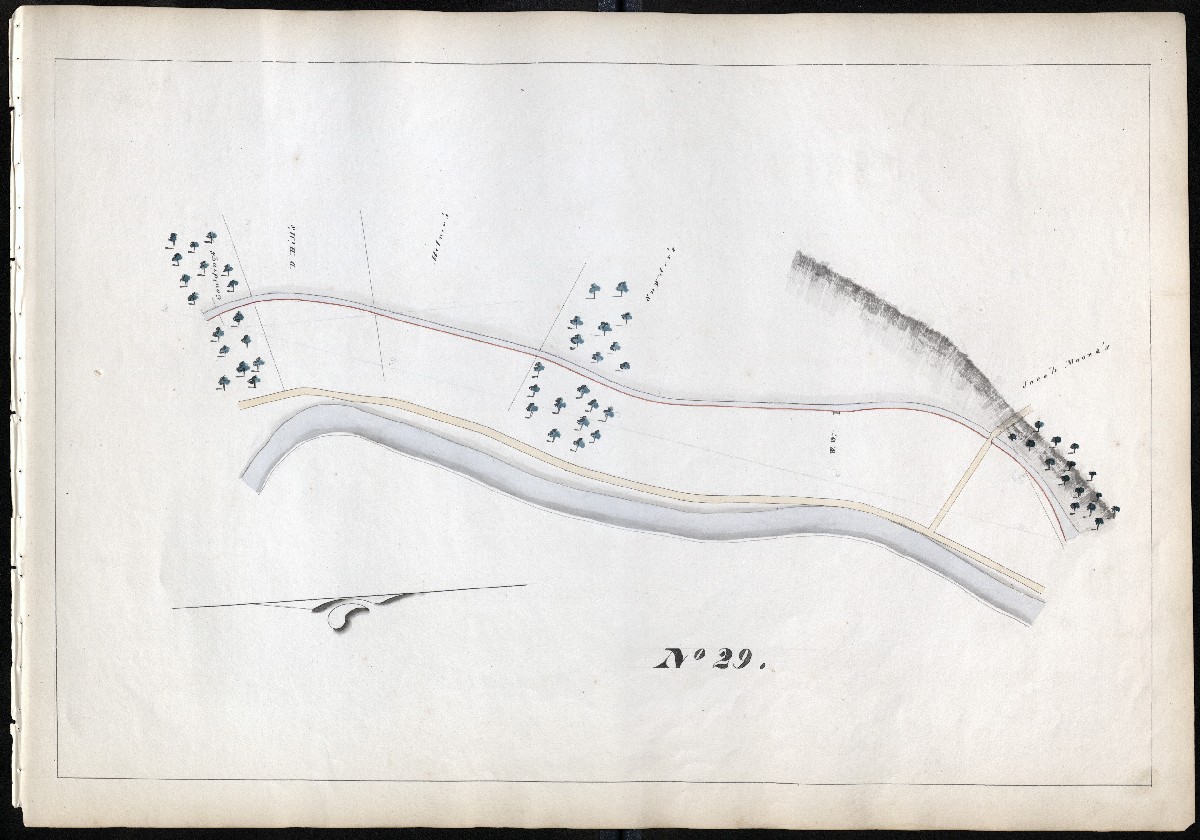

MILE 29

Hamburg Canal between Lock 33 and Lock 34/35, Mohrsville

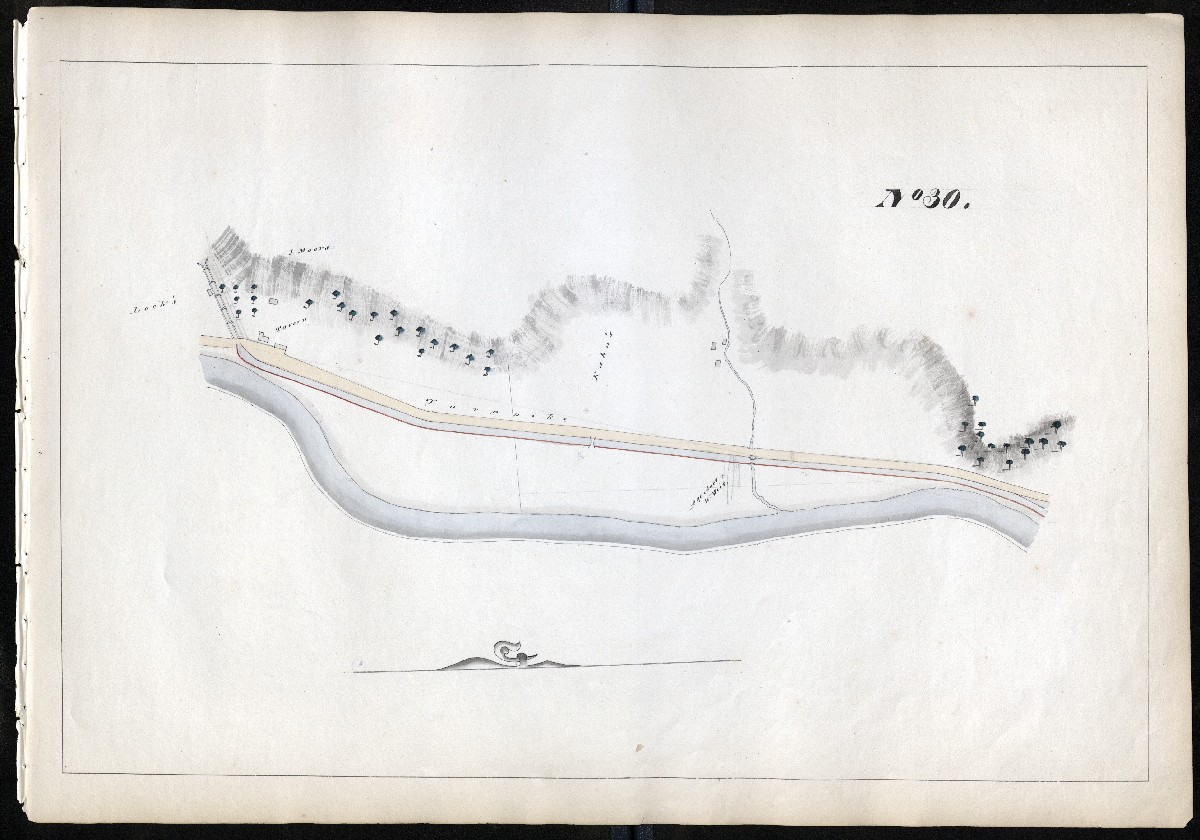

MILE 30

Hamburg Canal, Mohrsville. Lock, four chambers became two, Lock 34/35, after 1846 enlargement. Unnamed aqueduct and waste weir.

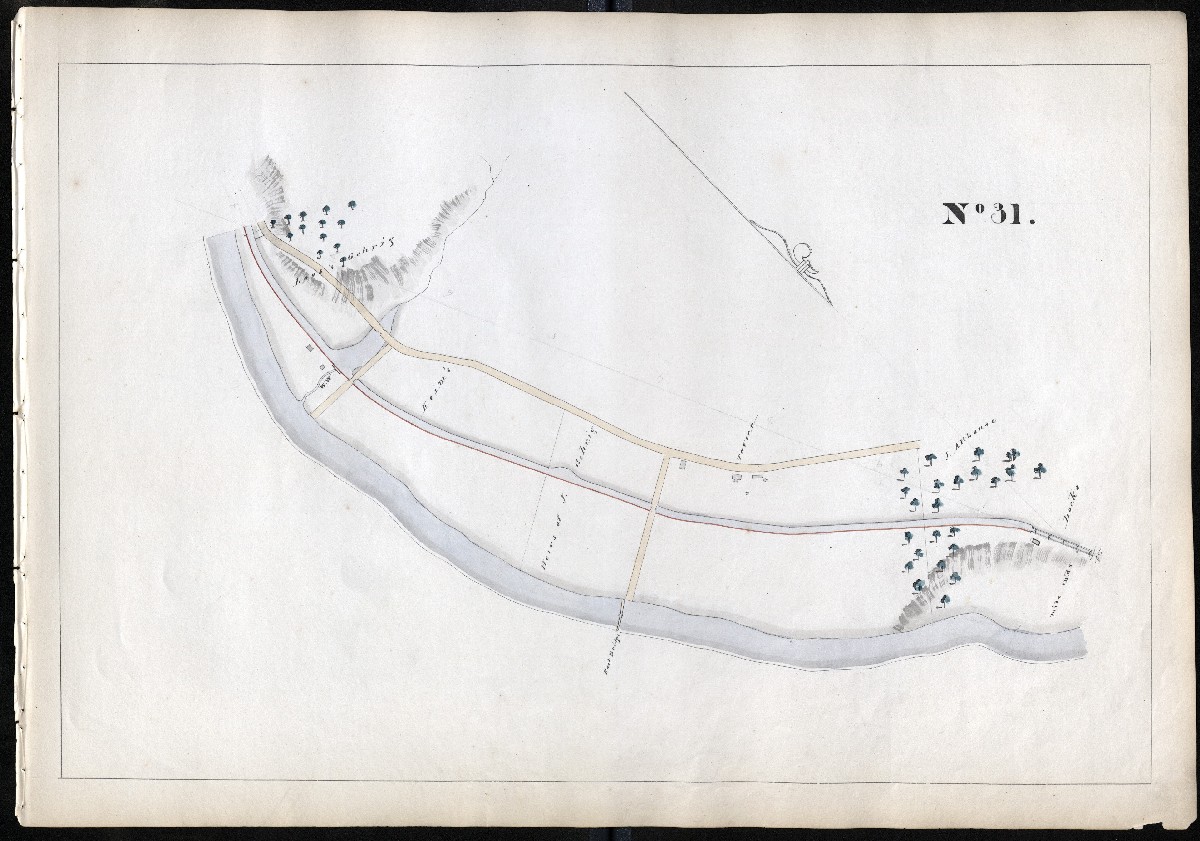

MILE 31

Hamburg Canal Outlet Locks, Leesport. Althouse Lock, four chambers, became two, Locks 36/37, after 1846 enlargement.

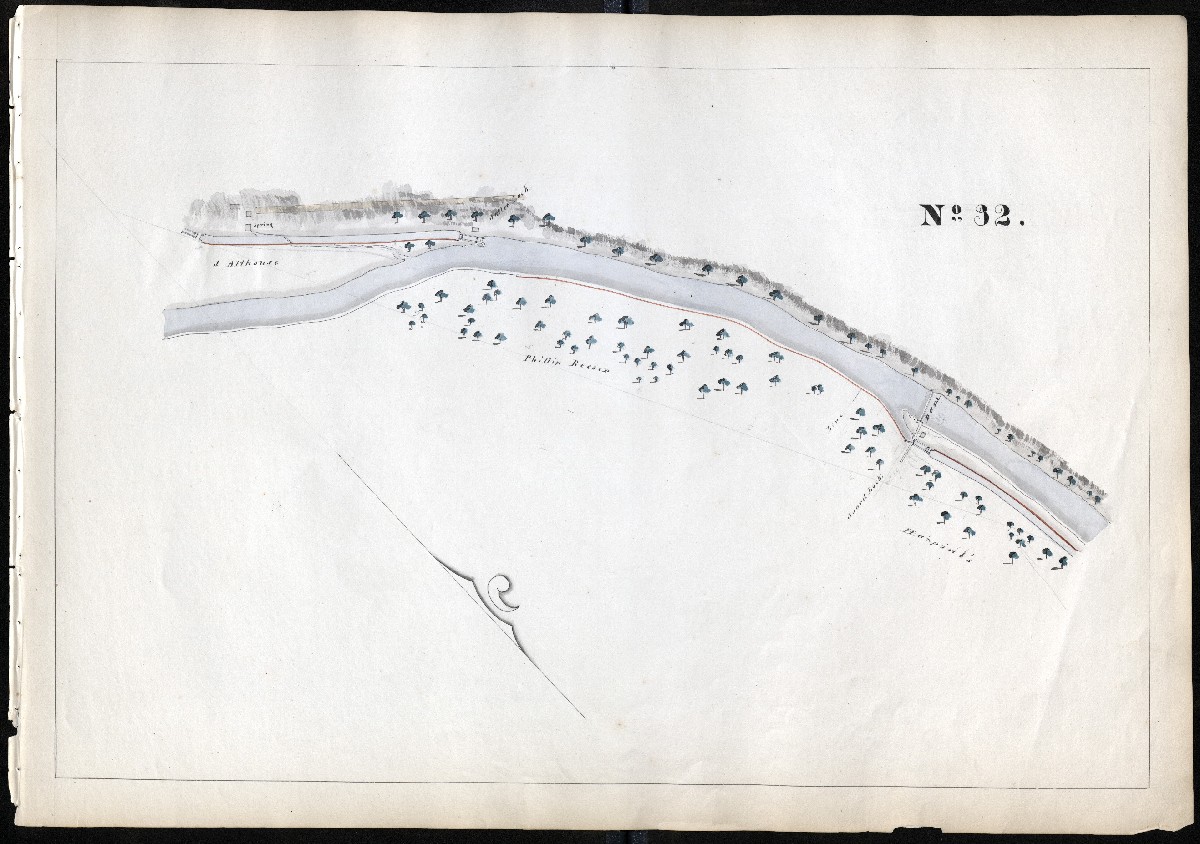

MILE 32

MILE 33

MILE 34

MILE 35

MILE 36

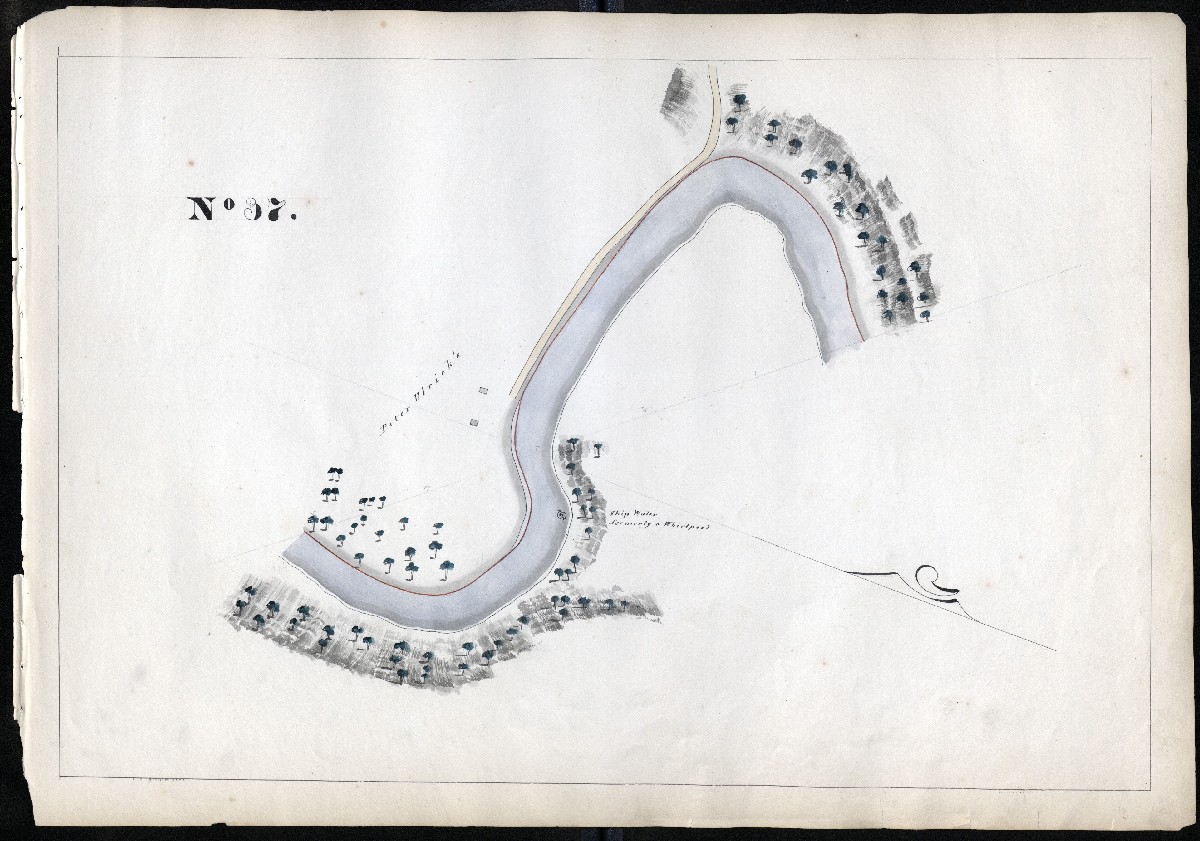

MILE 37

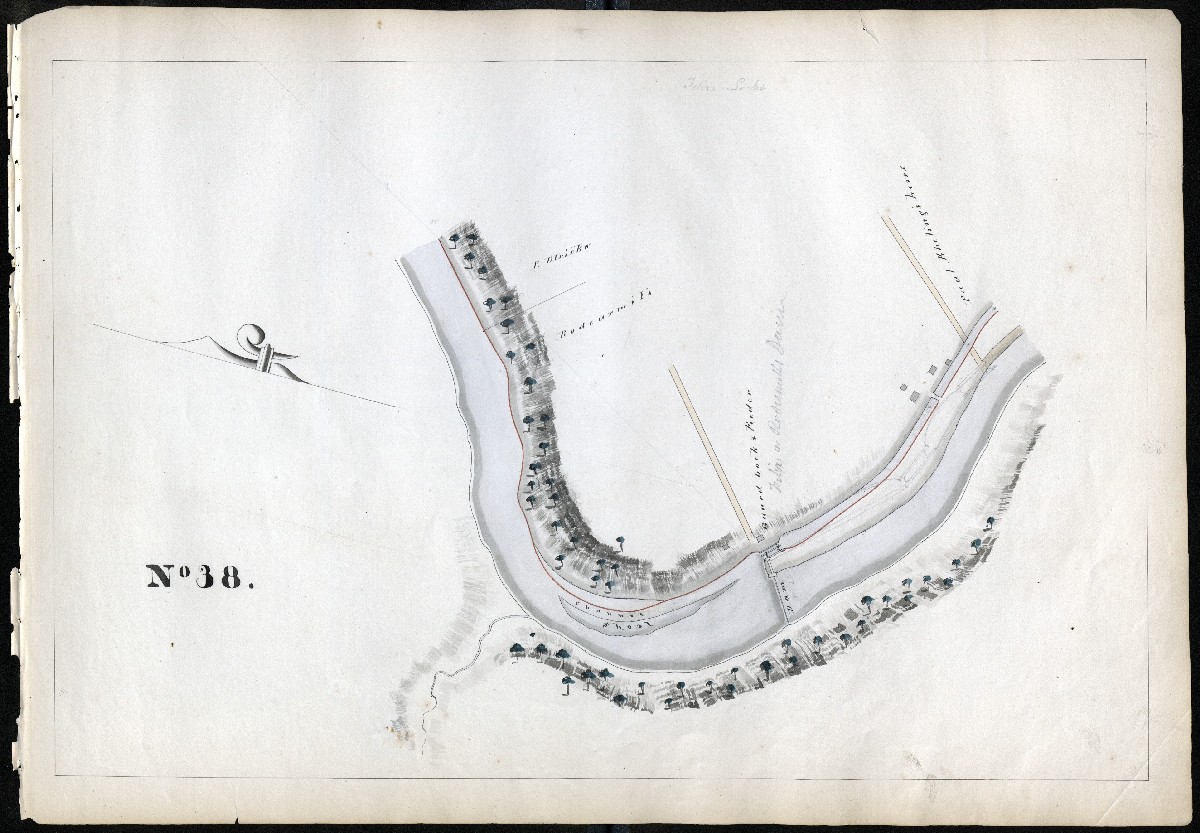

MILE 38

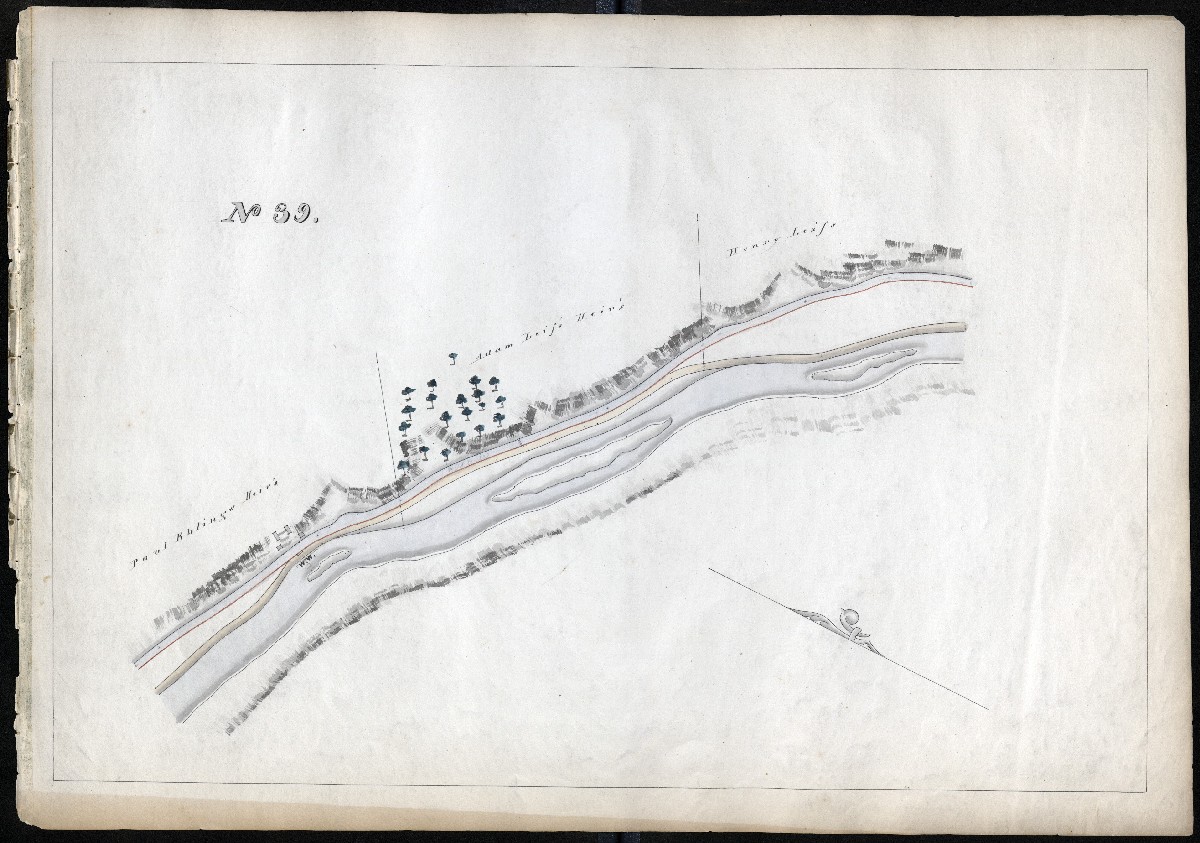

MILE 39

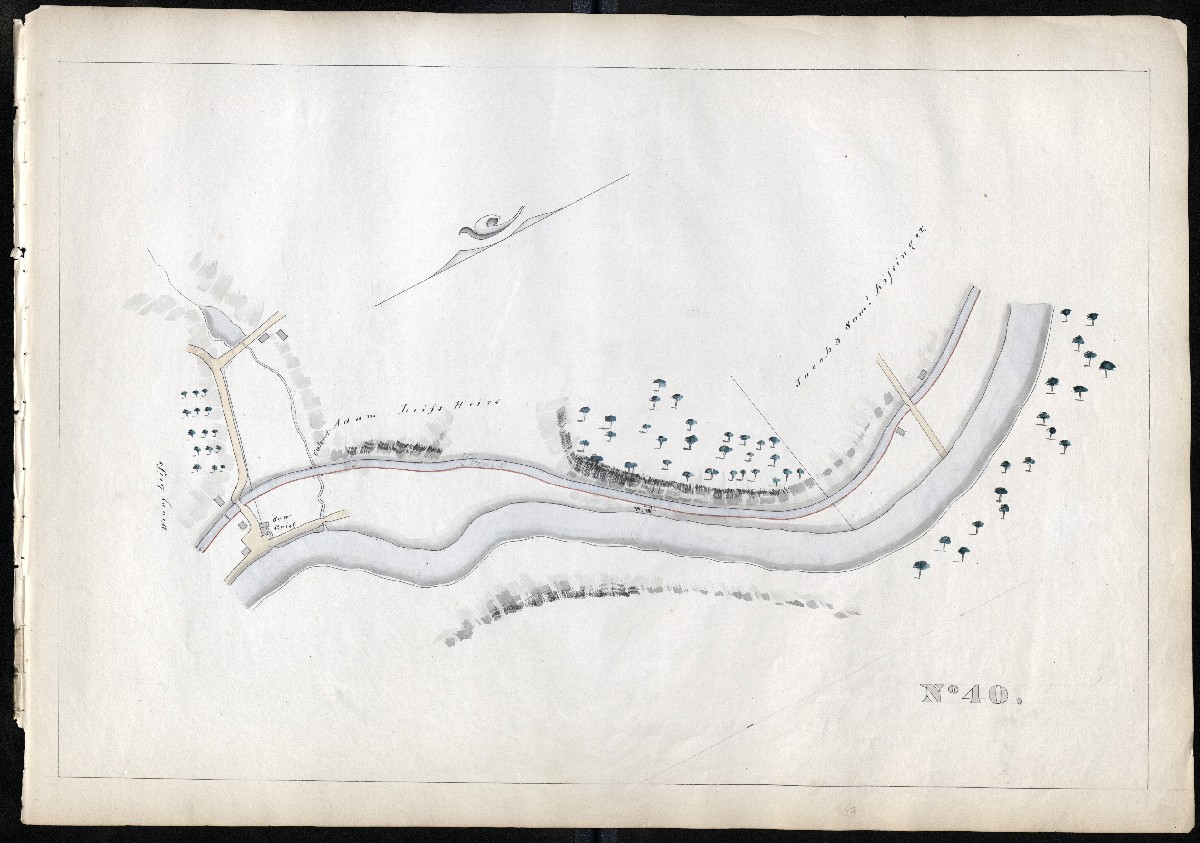

MILE 40

MILE 41

MILE 42

MILE 43

MILE 44

MILE 45

MILE 46

MILE 47

MILE 48

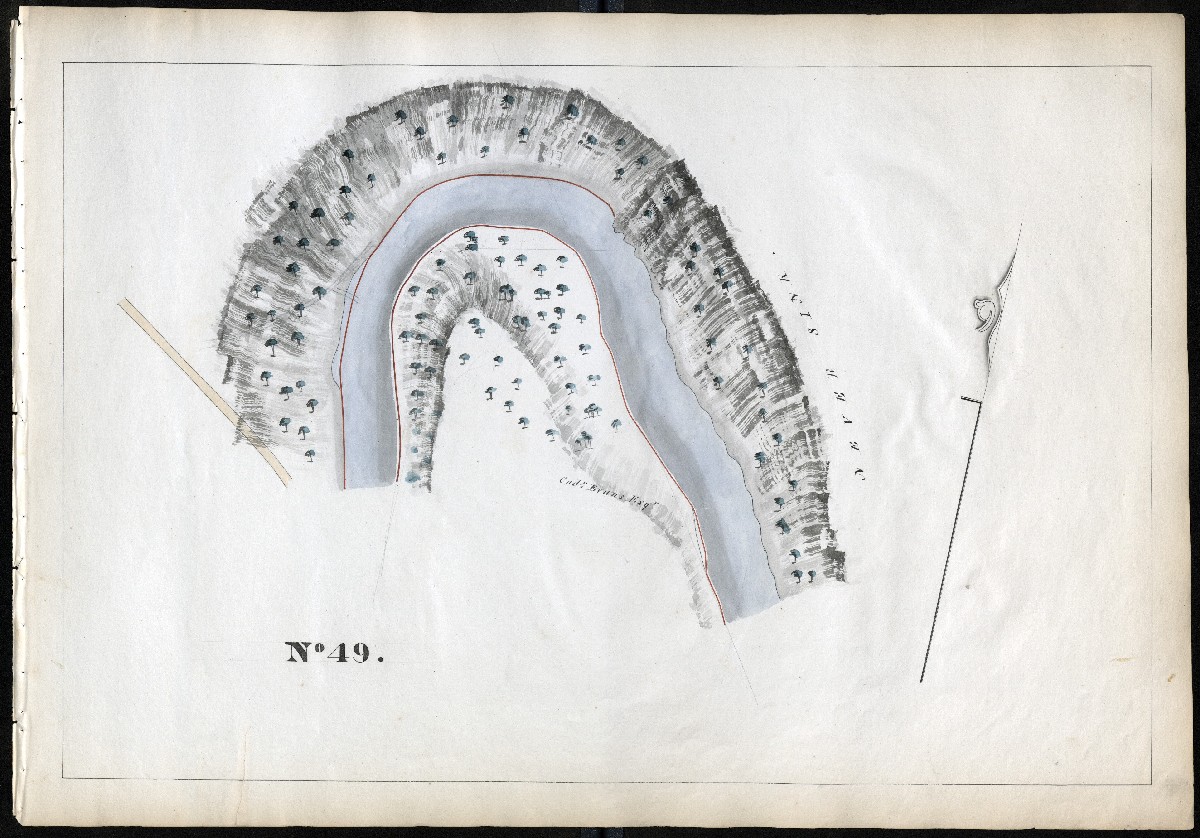

MILE 49

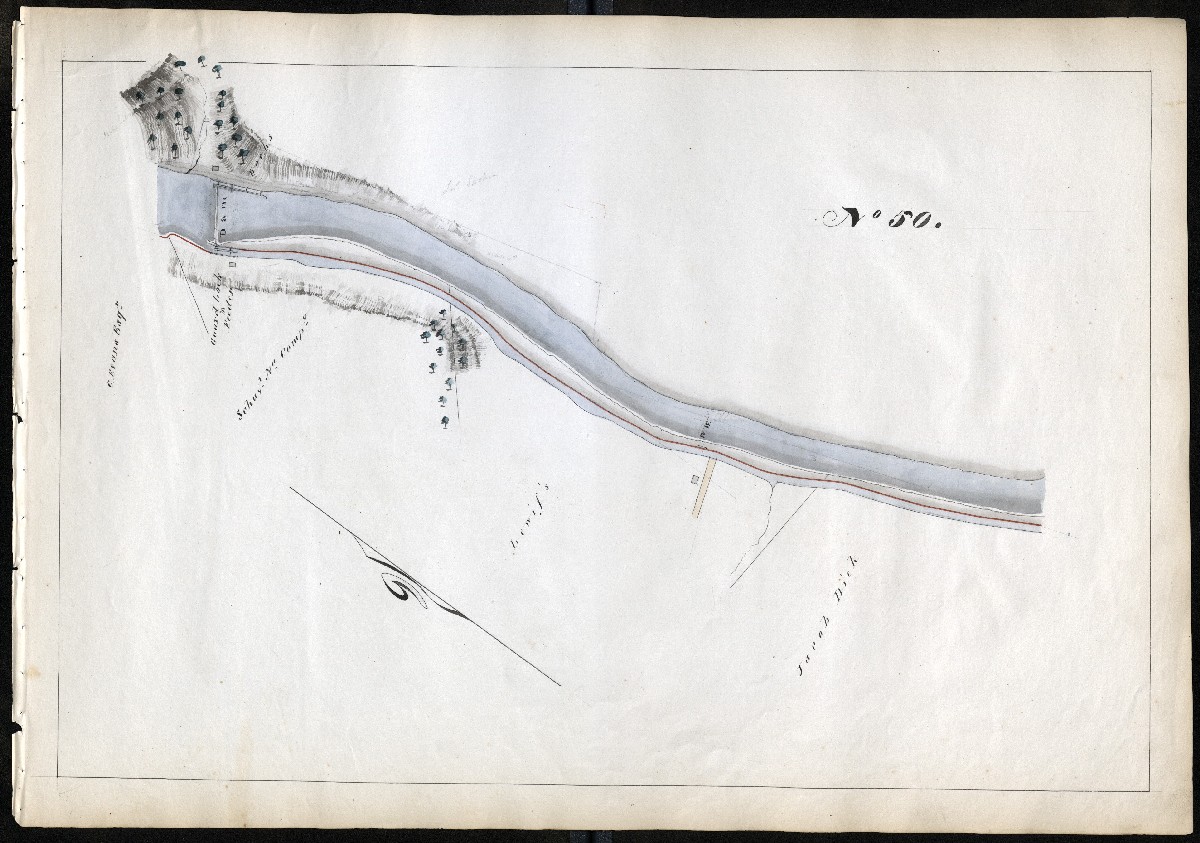

MILE 50

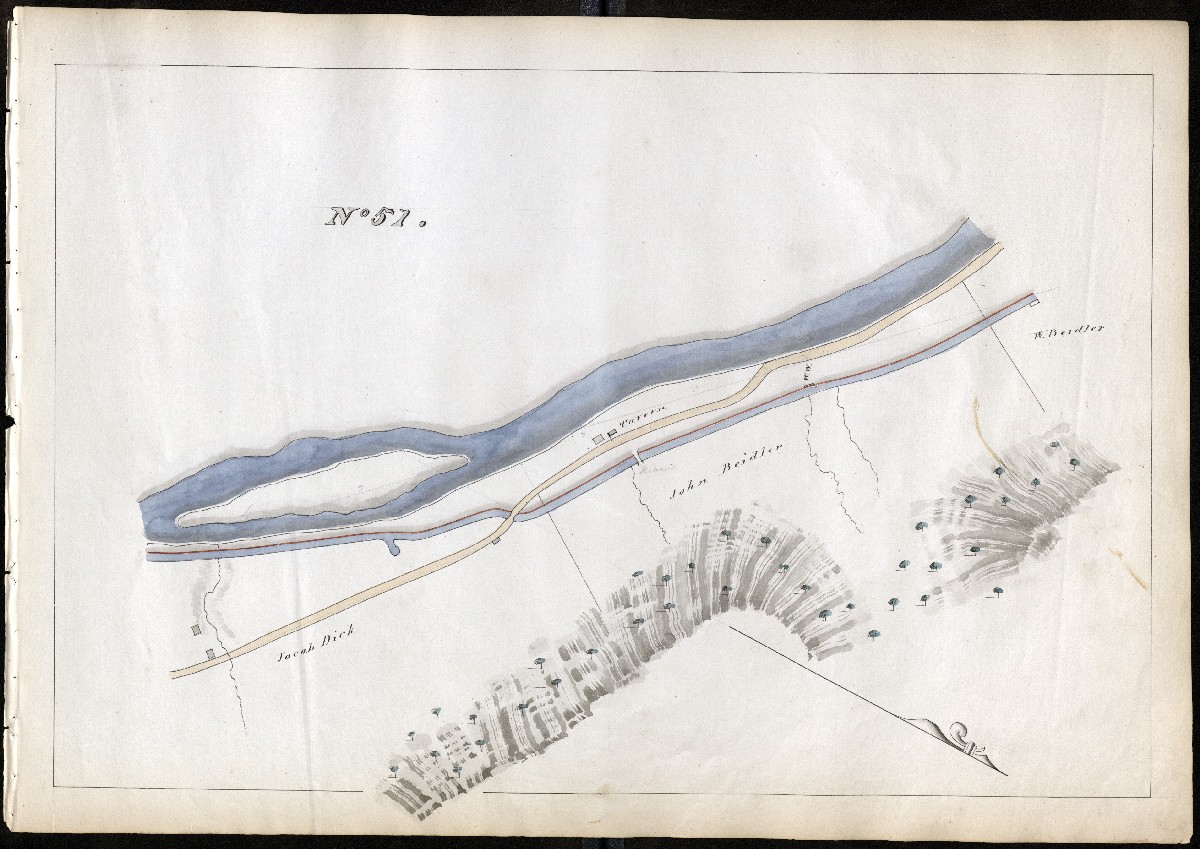

MILE 51

MILE 52

MILE 53

MILE 54

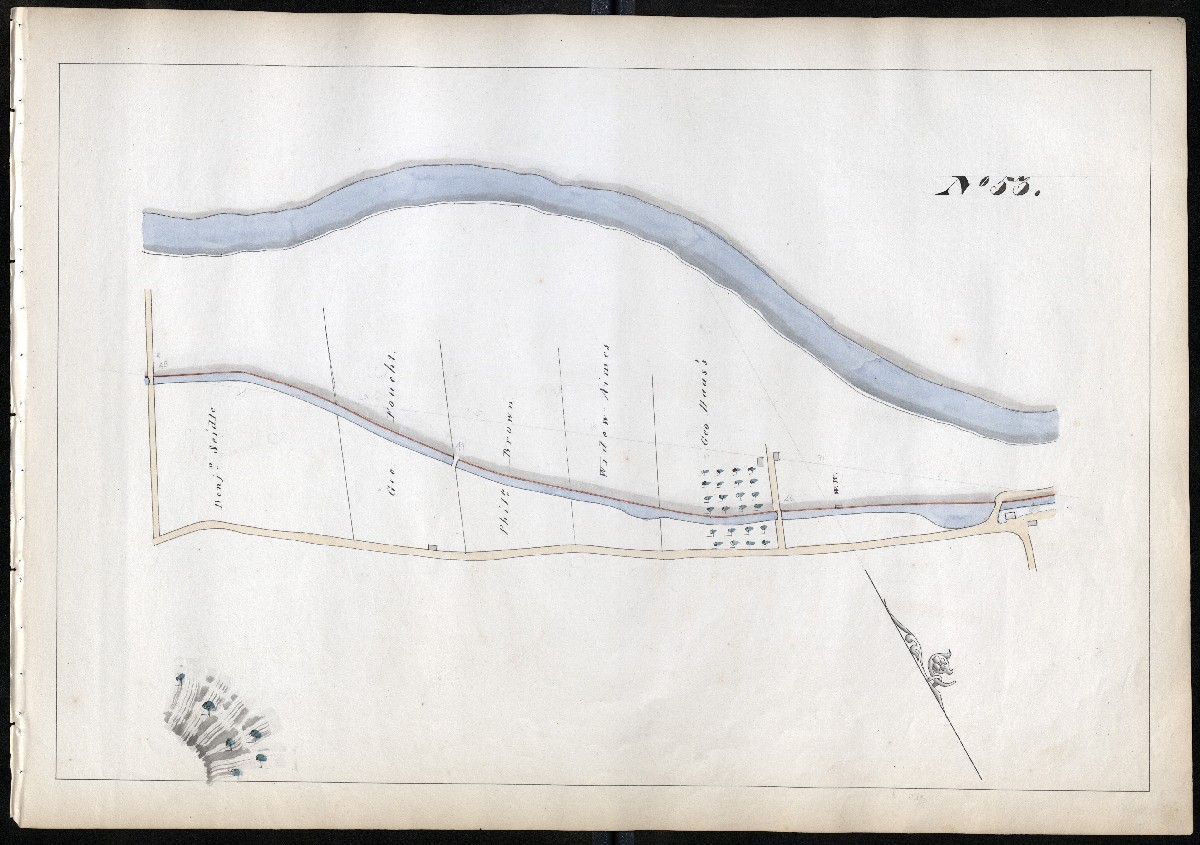

MILE 55

MILE 56

MILE 57

MILE 58

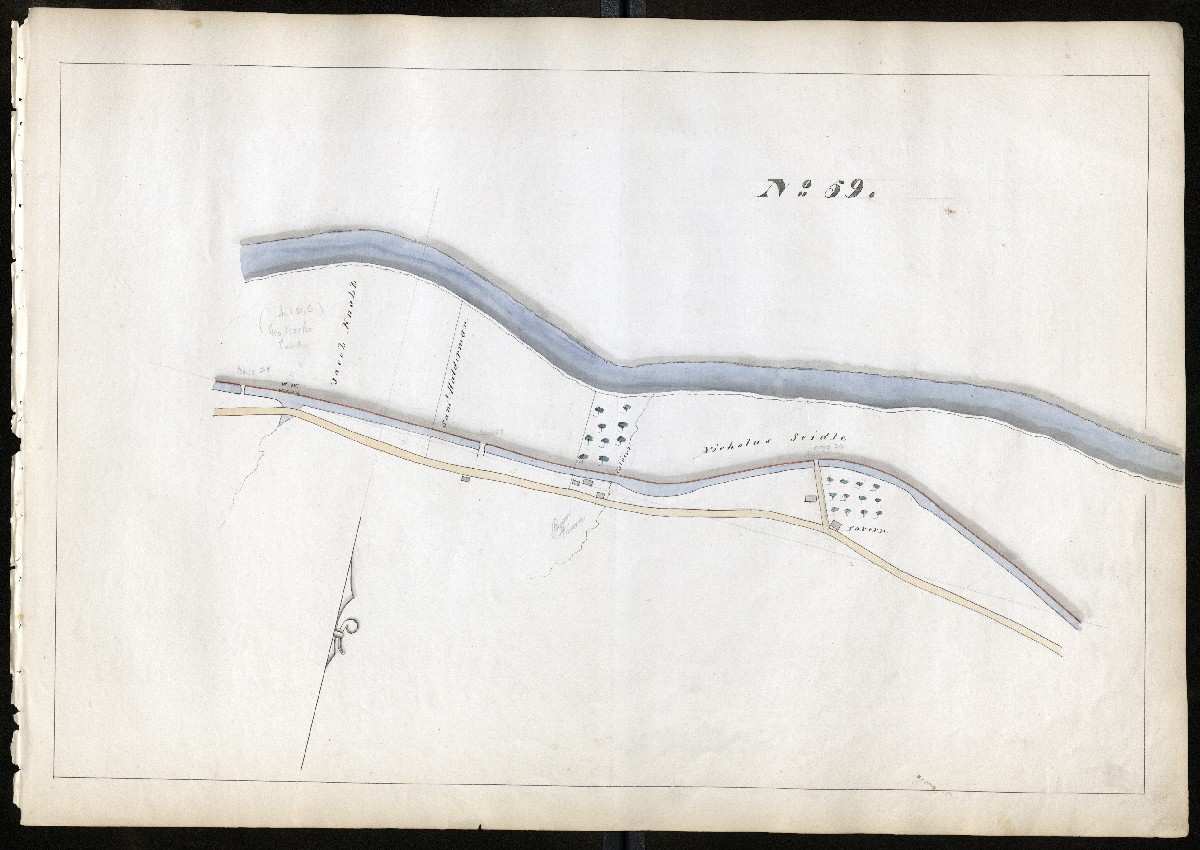

MILE 59

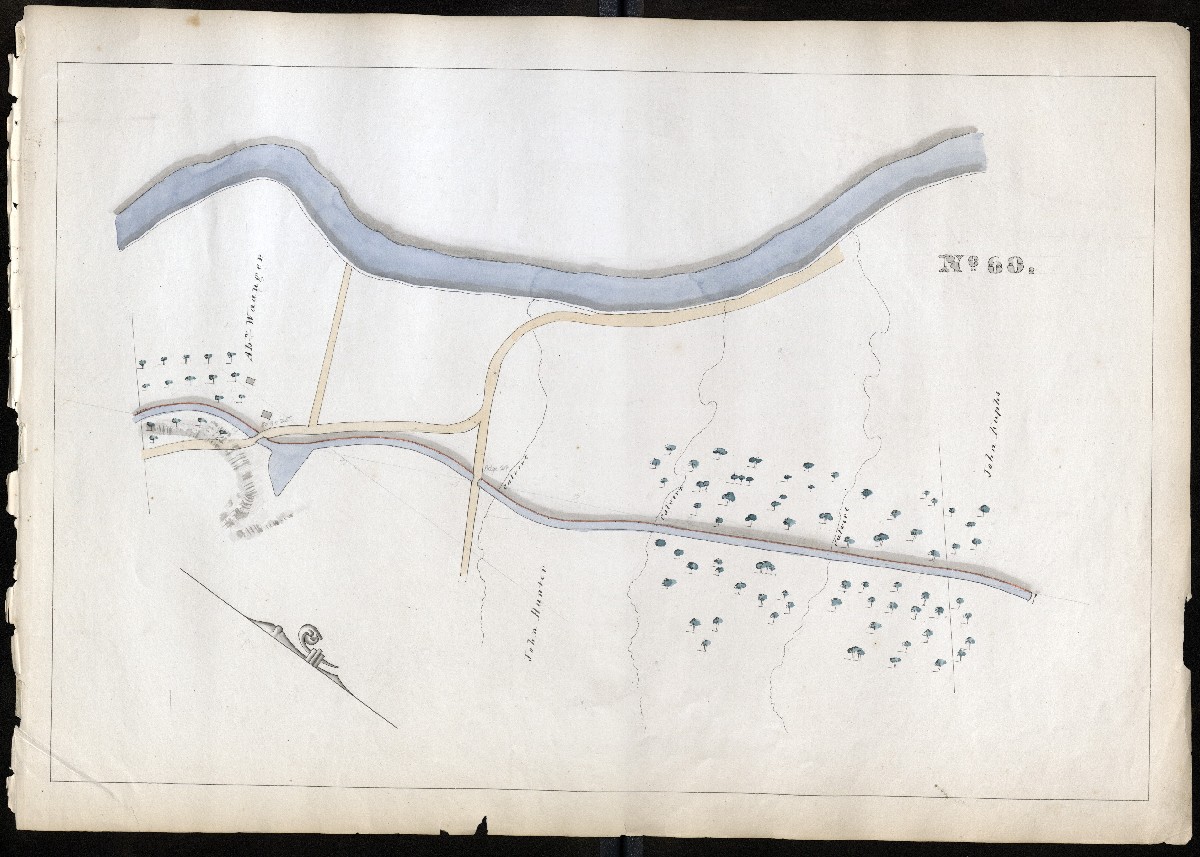

MILE 60

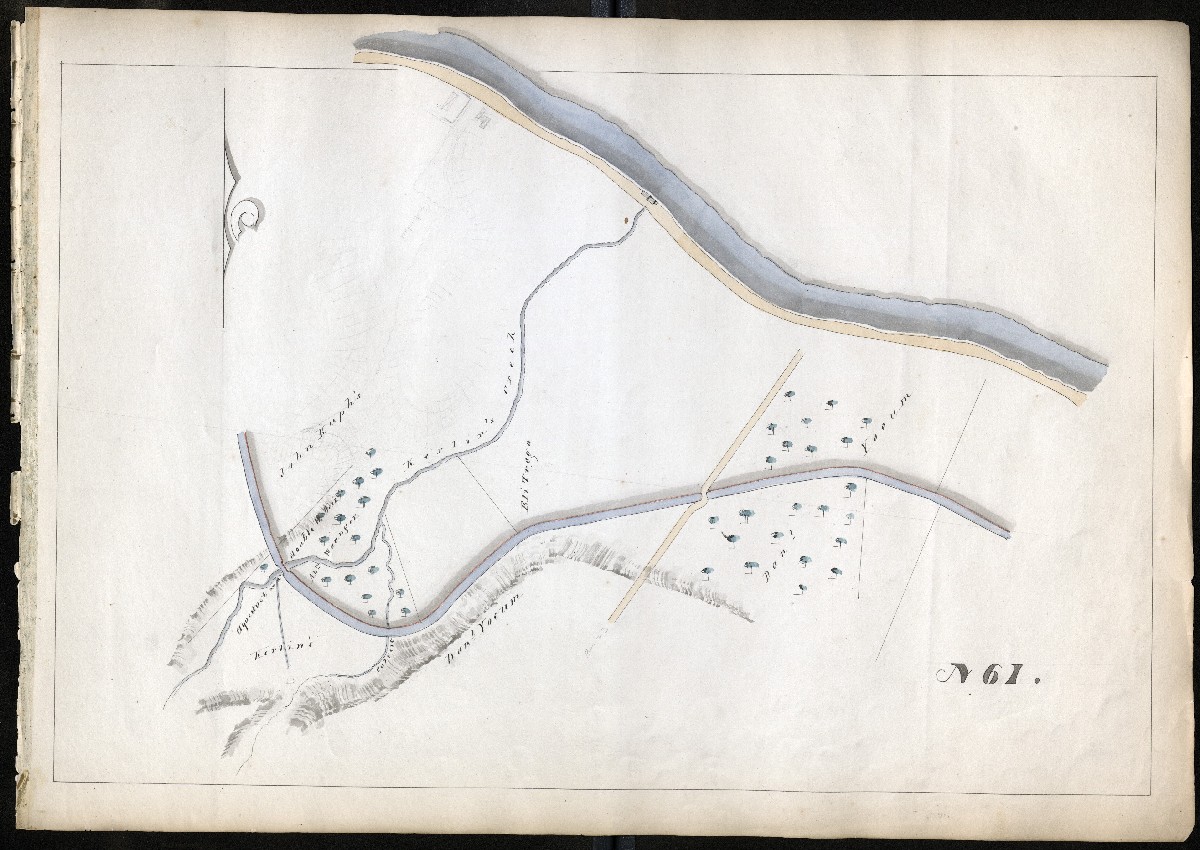

MILE 61

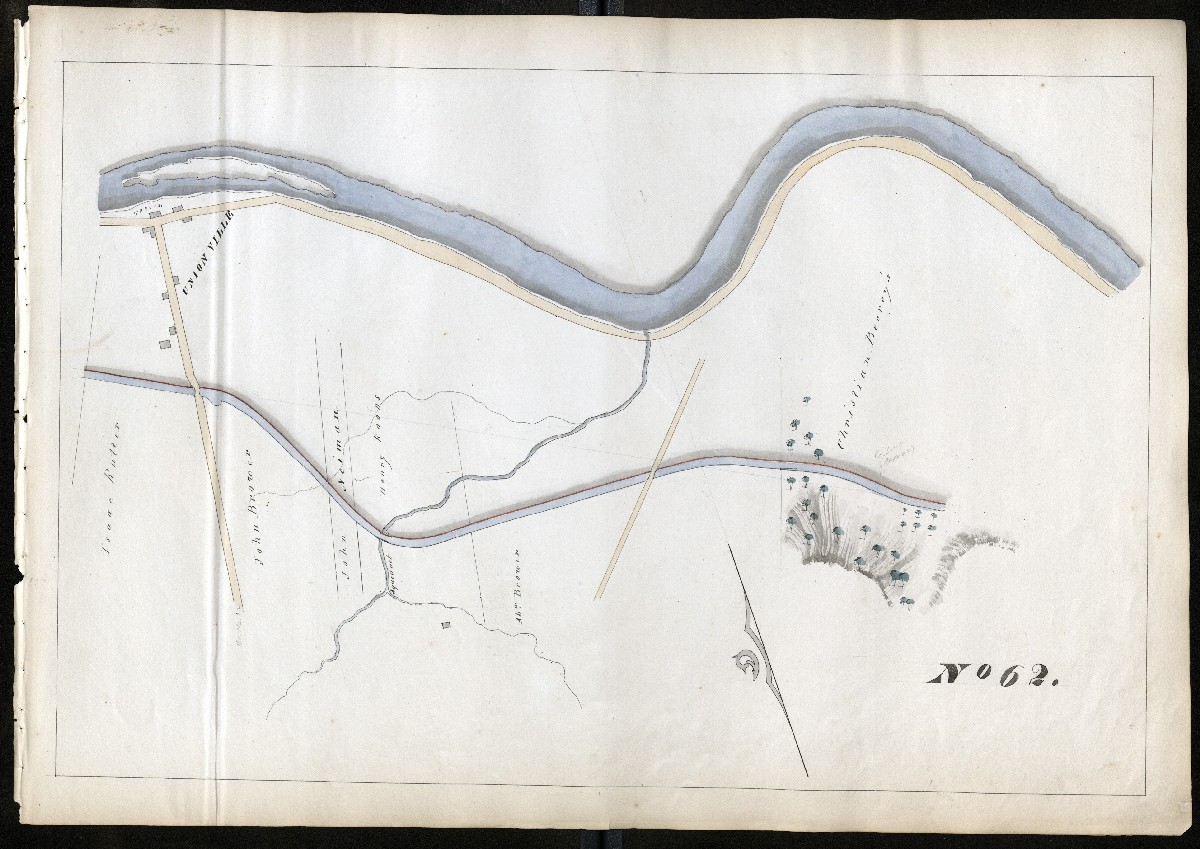

MILE 62

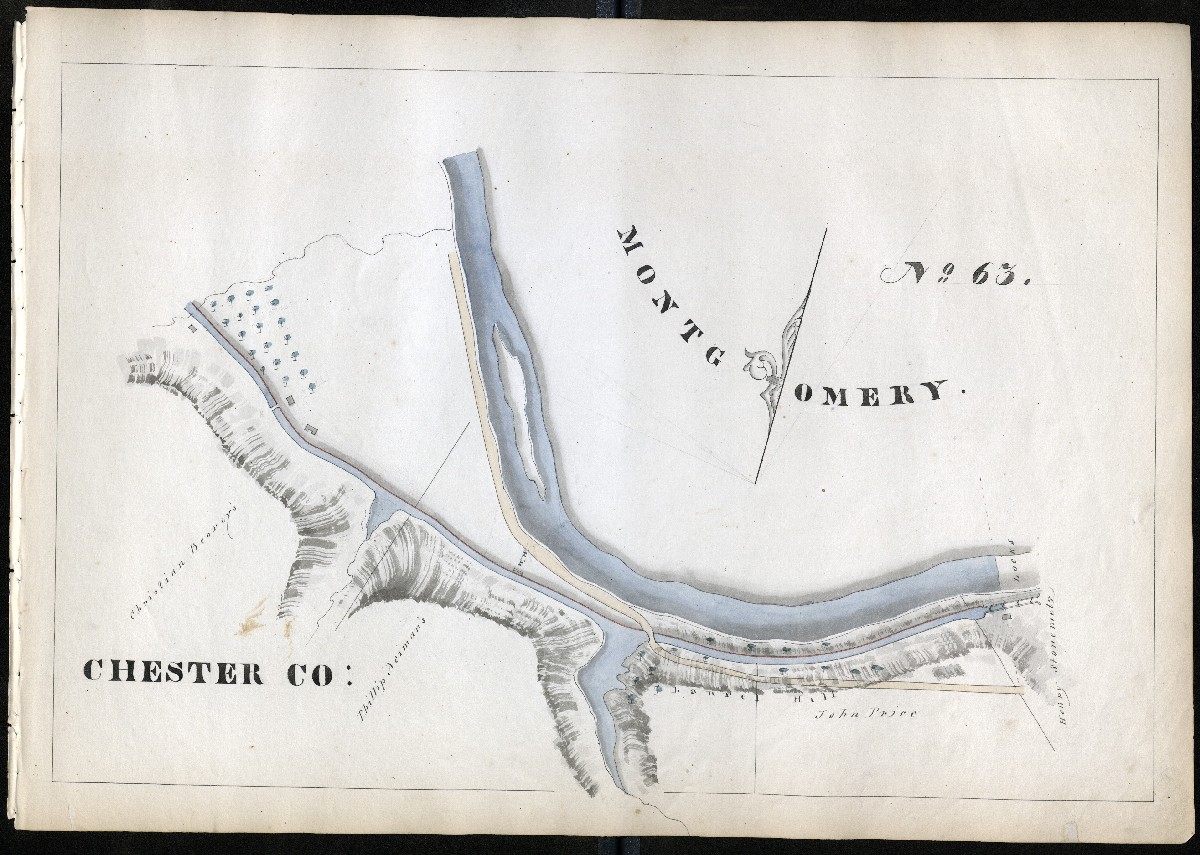

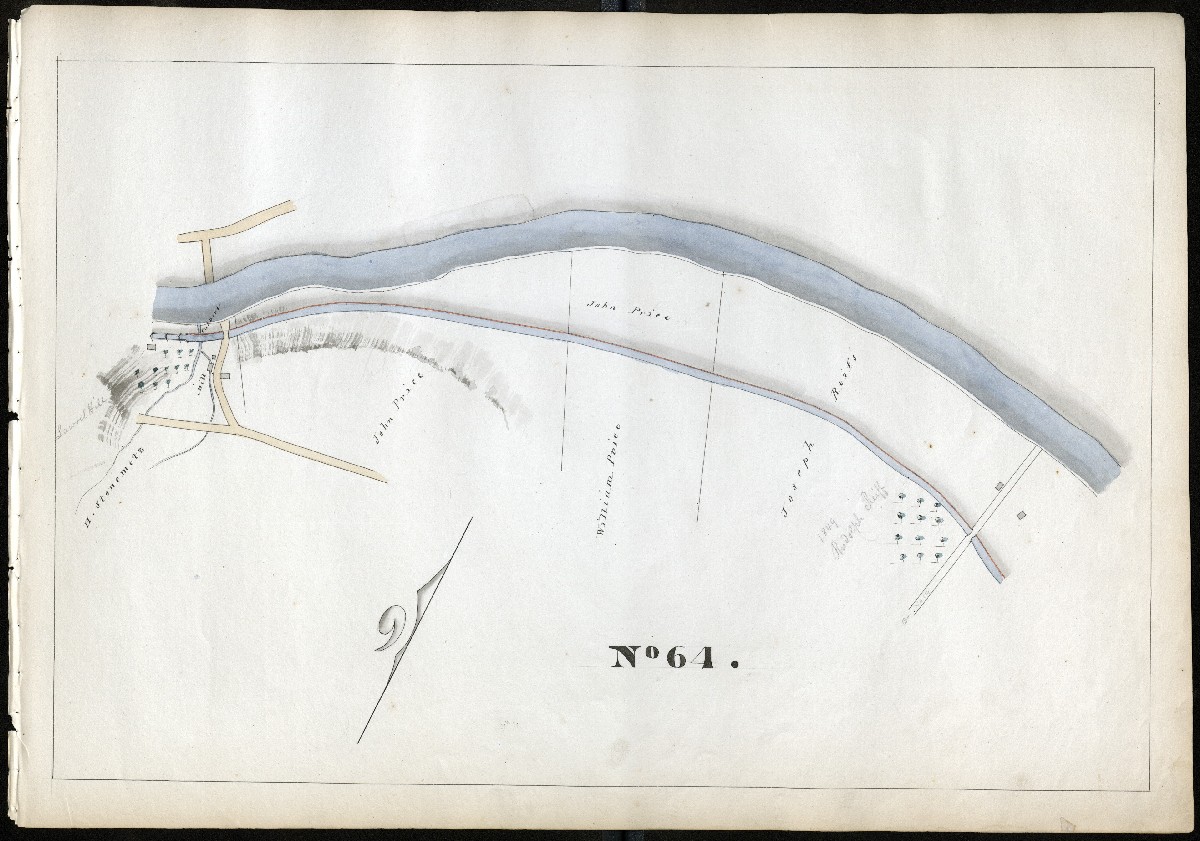

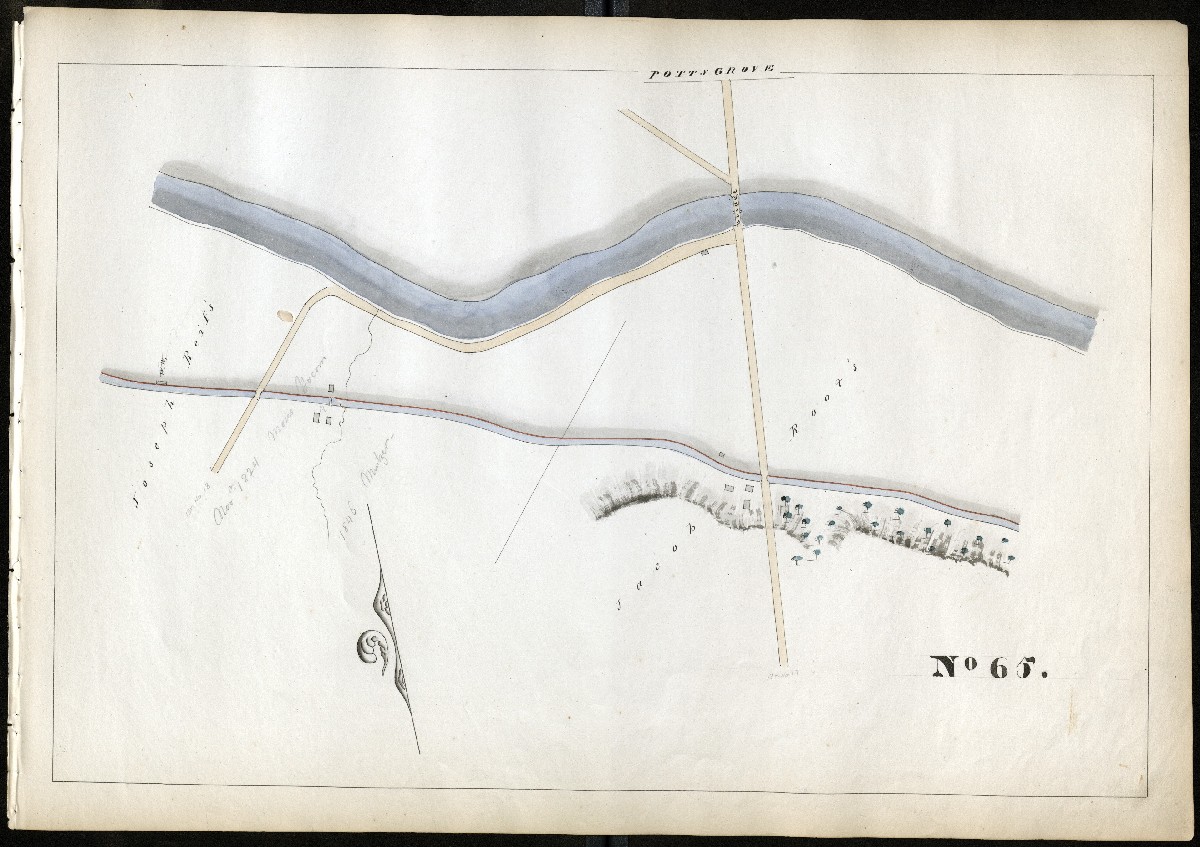

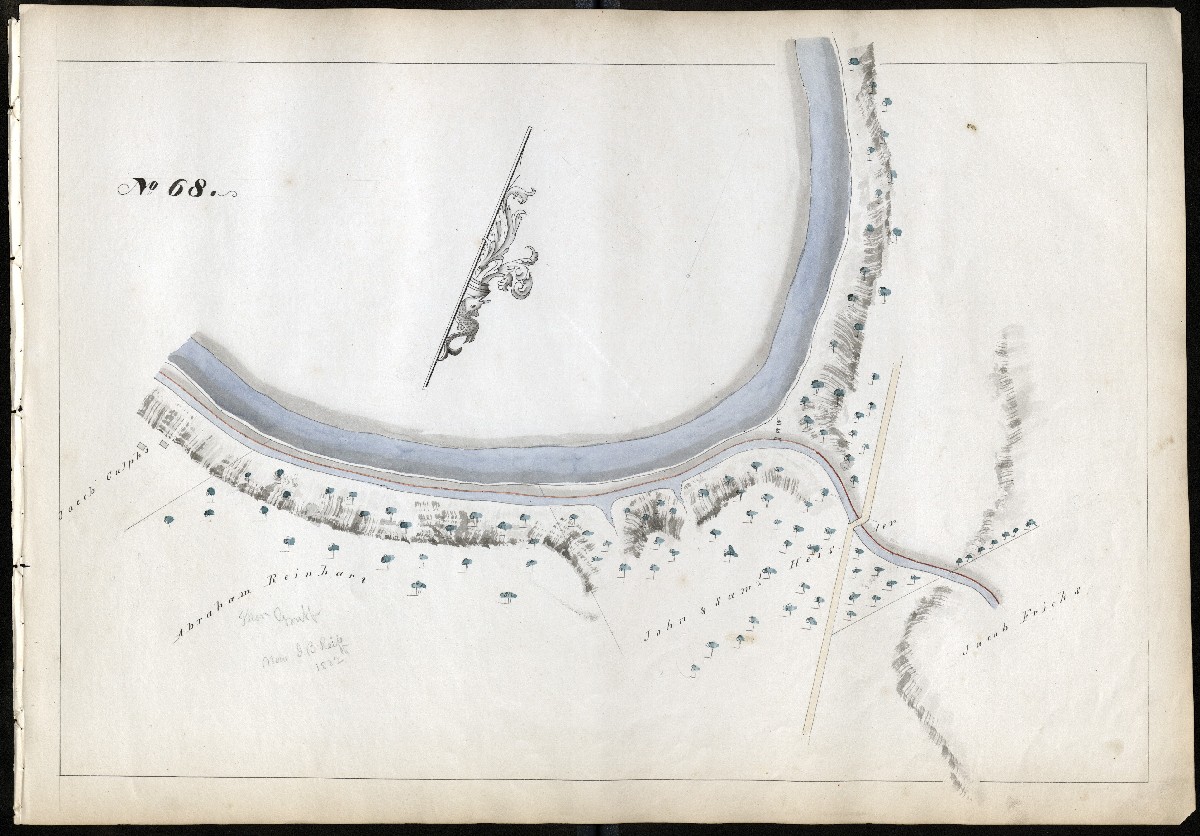

Chester County, Miles 63-85

MILE 63

MILE 64

MILE 65

MILE 66

MILE 67

MILE 68

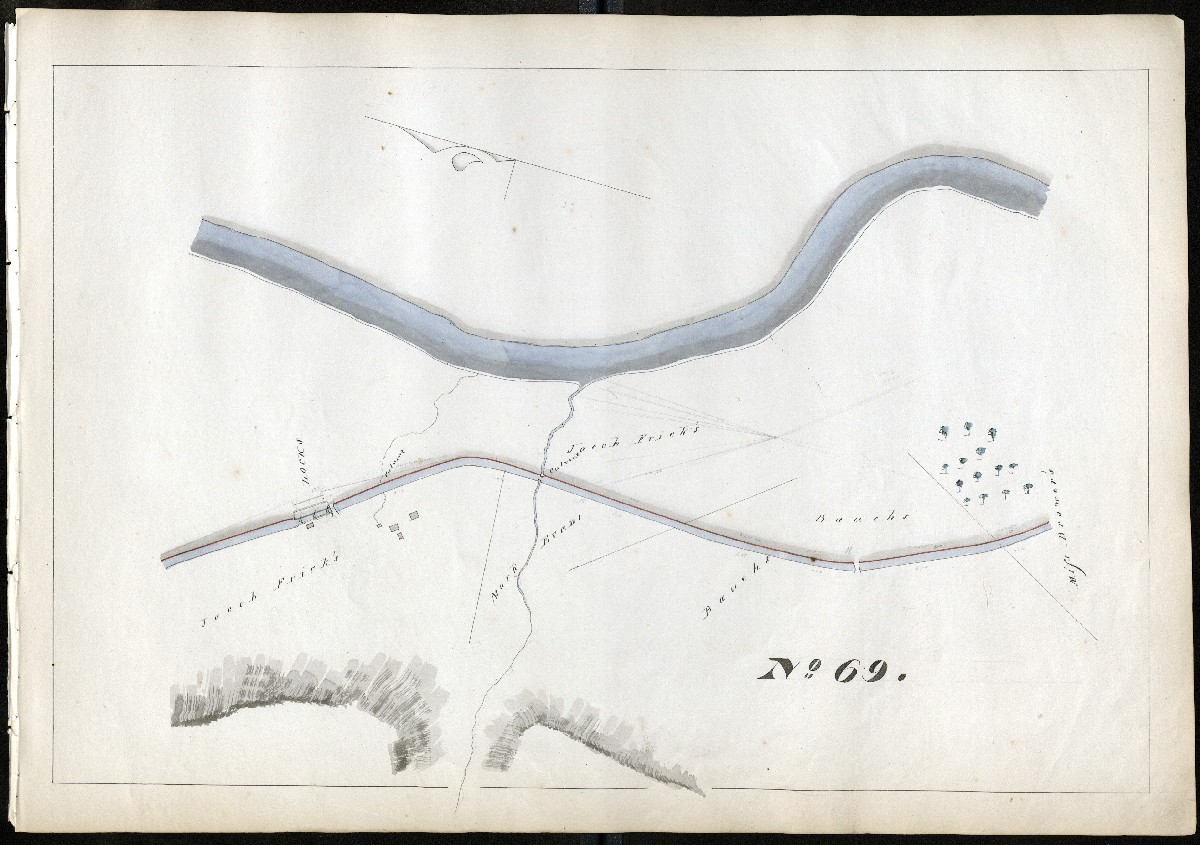

MILE 69

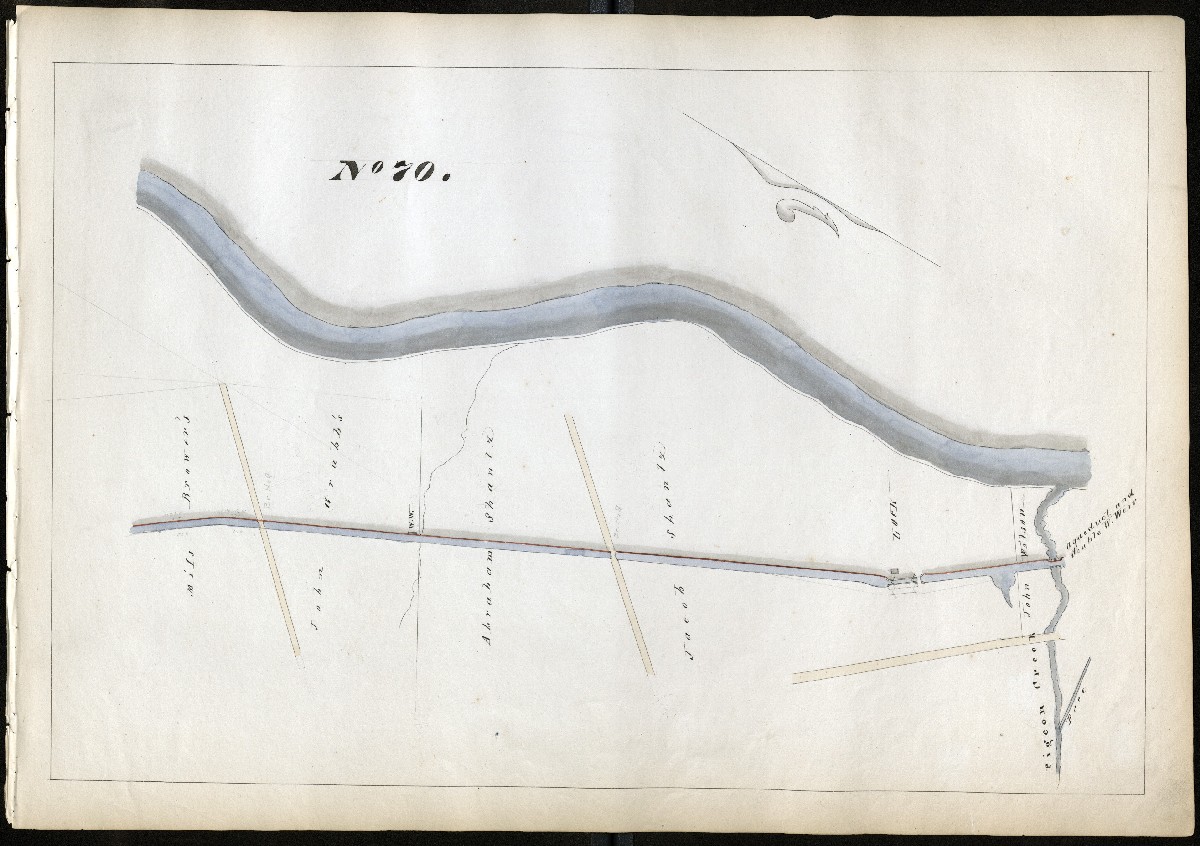

MILE 70

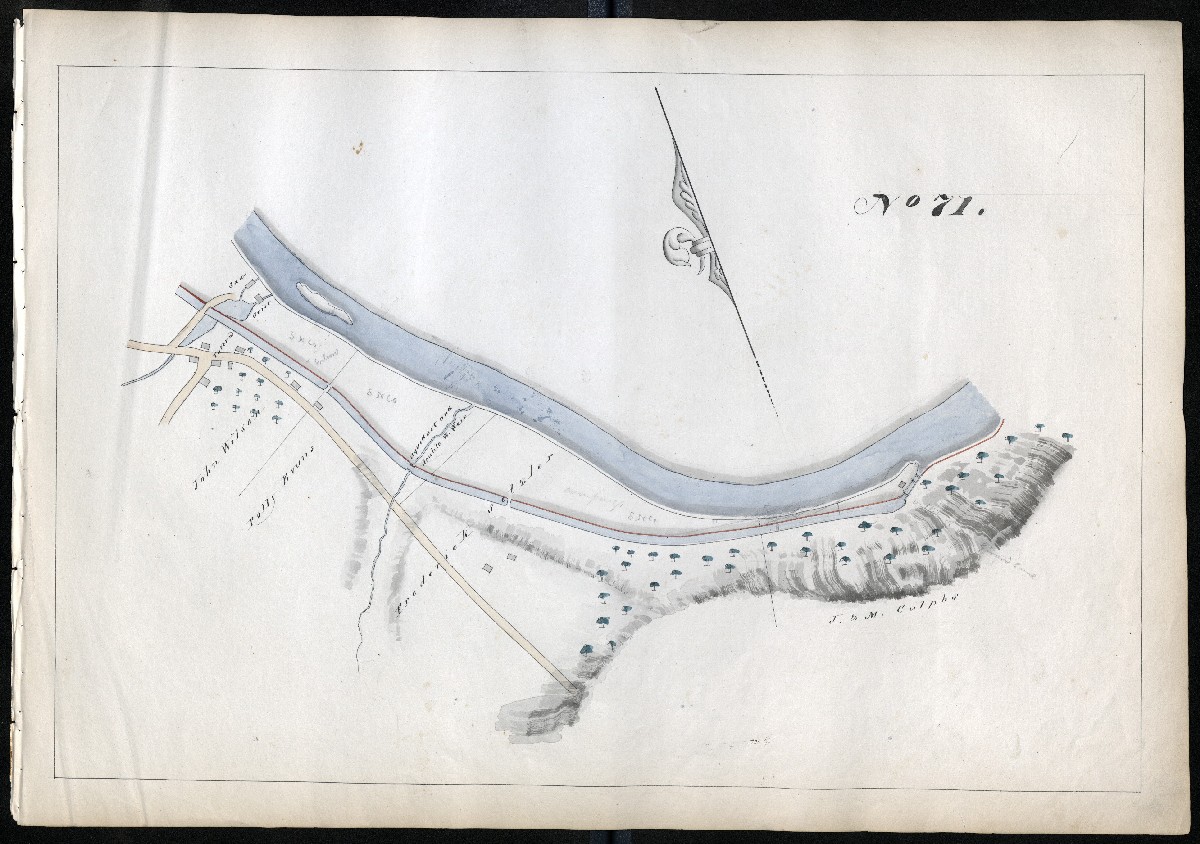

MILE 71

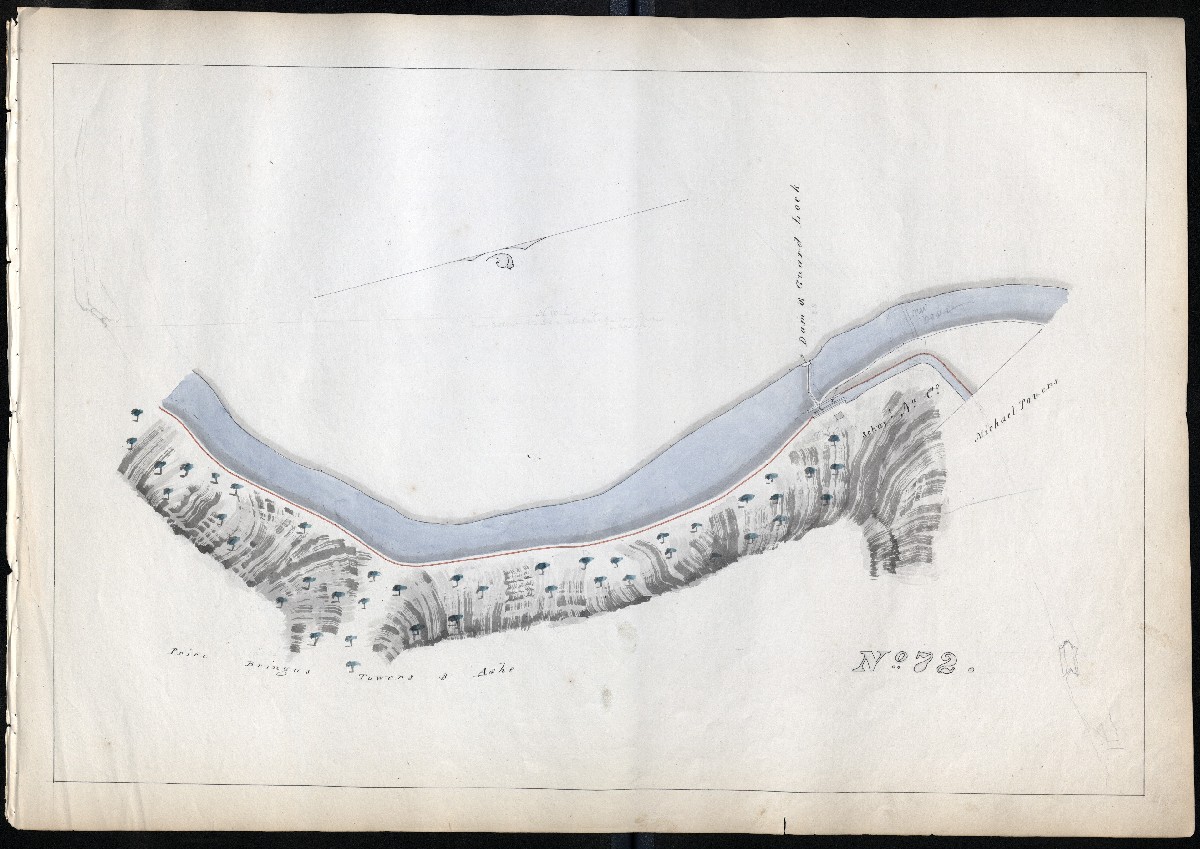

MILE 72

MILE 73

MILE 74

MILE 75

MILE 76

MILE 77

MILE 78

MILE 79

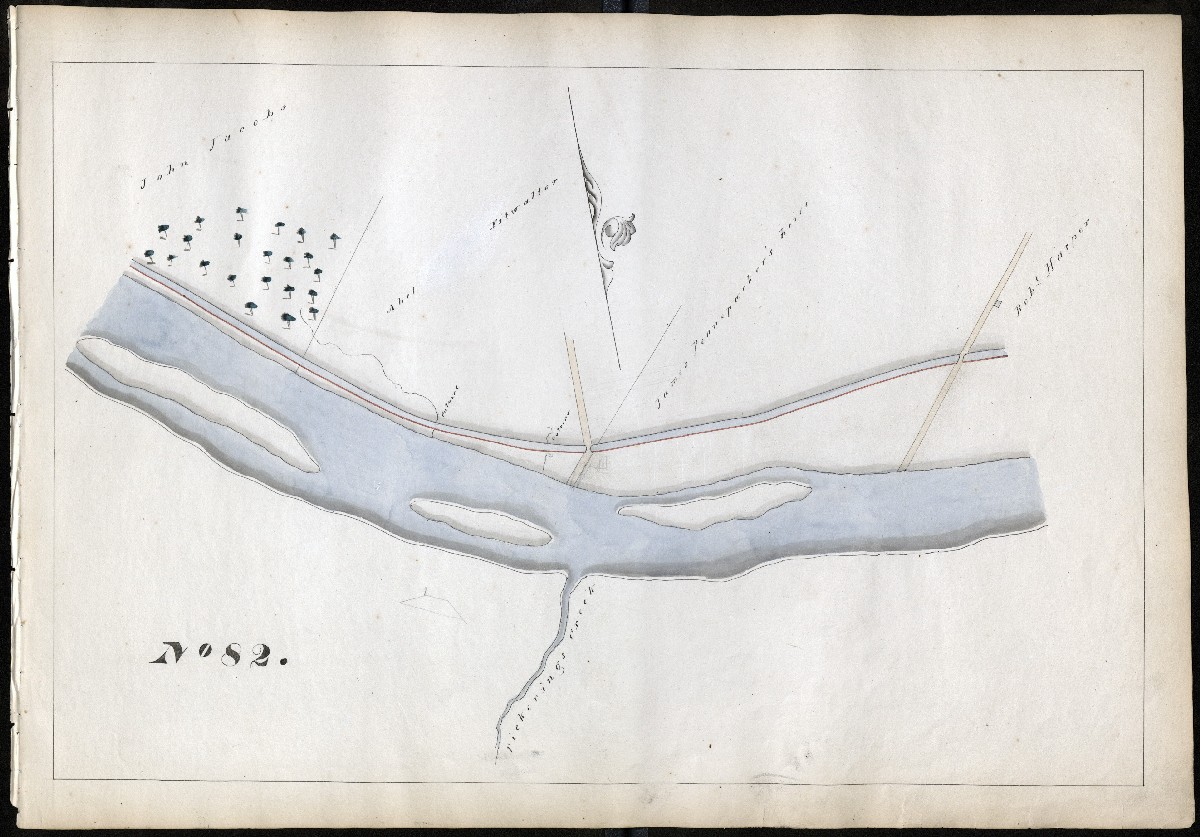

MILE 80

MILE 81

MILE 82

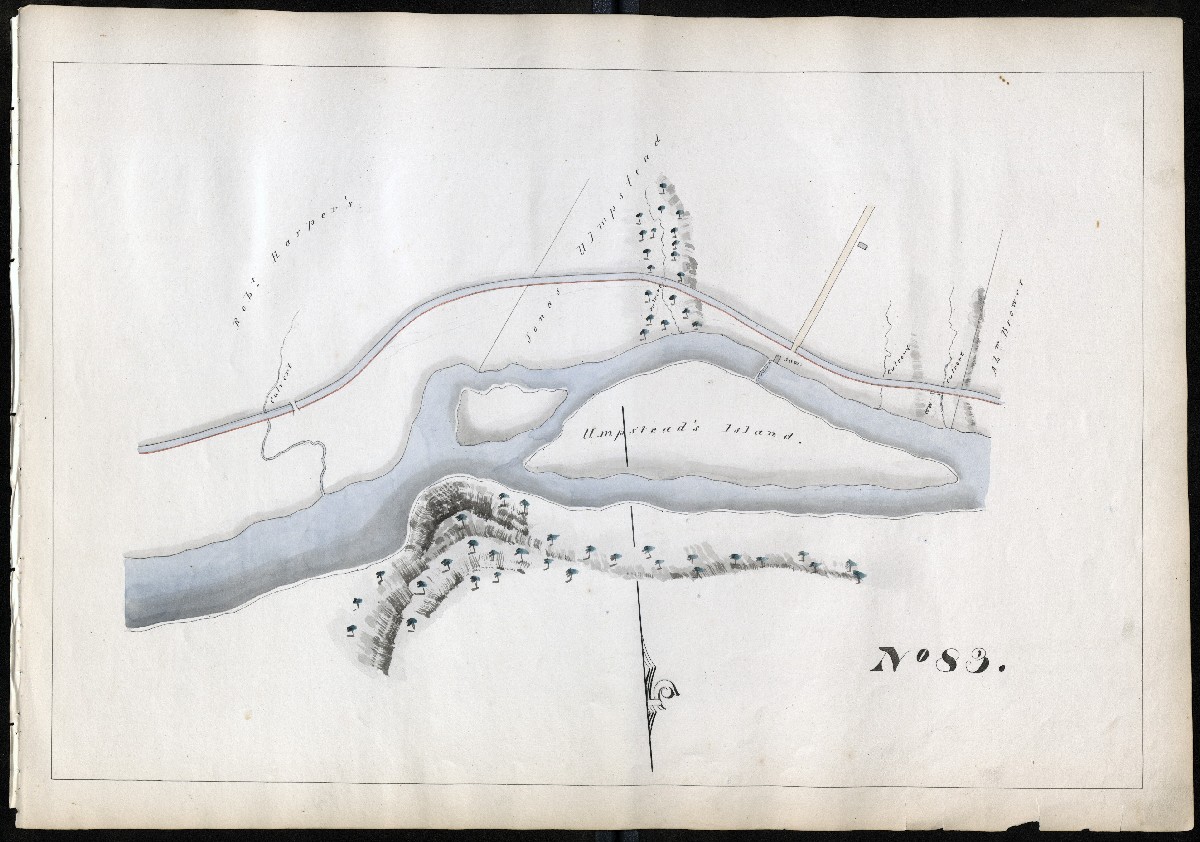

MILE 83

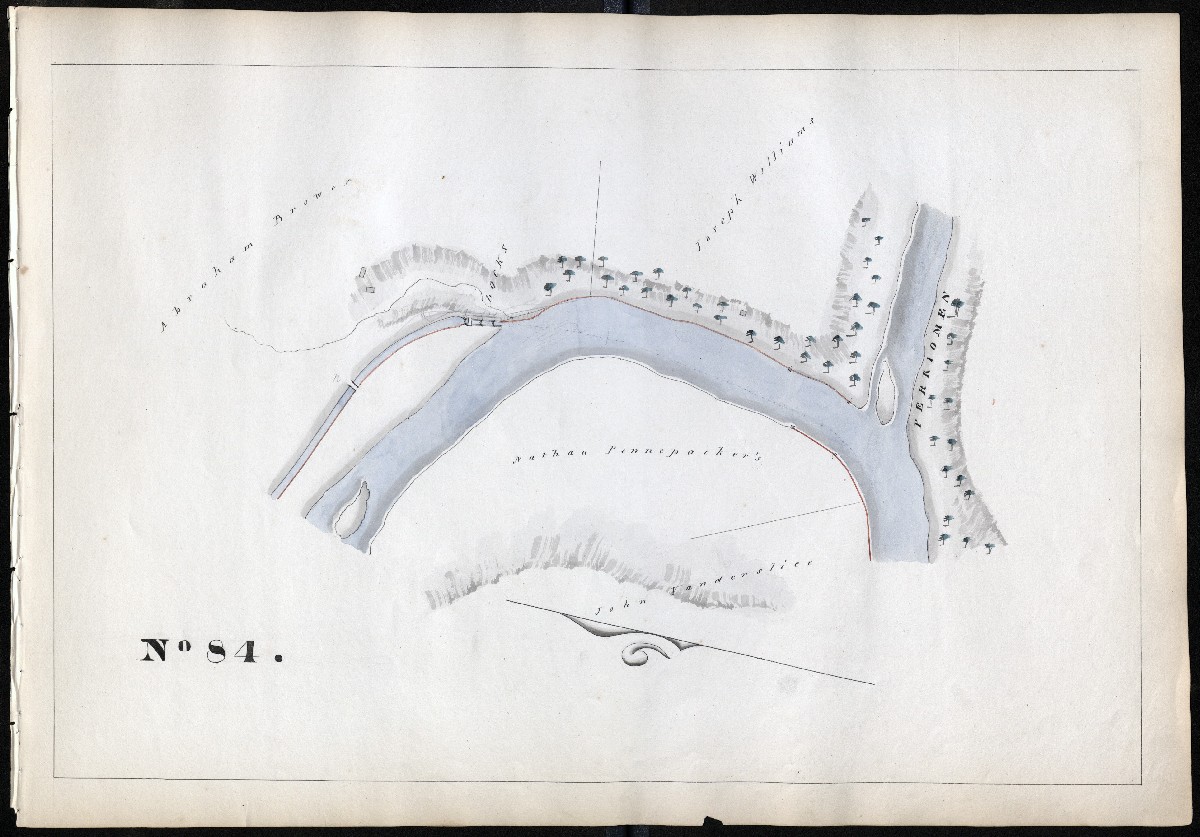

MILE 84

MILE 85

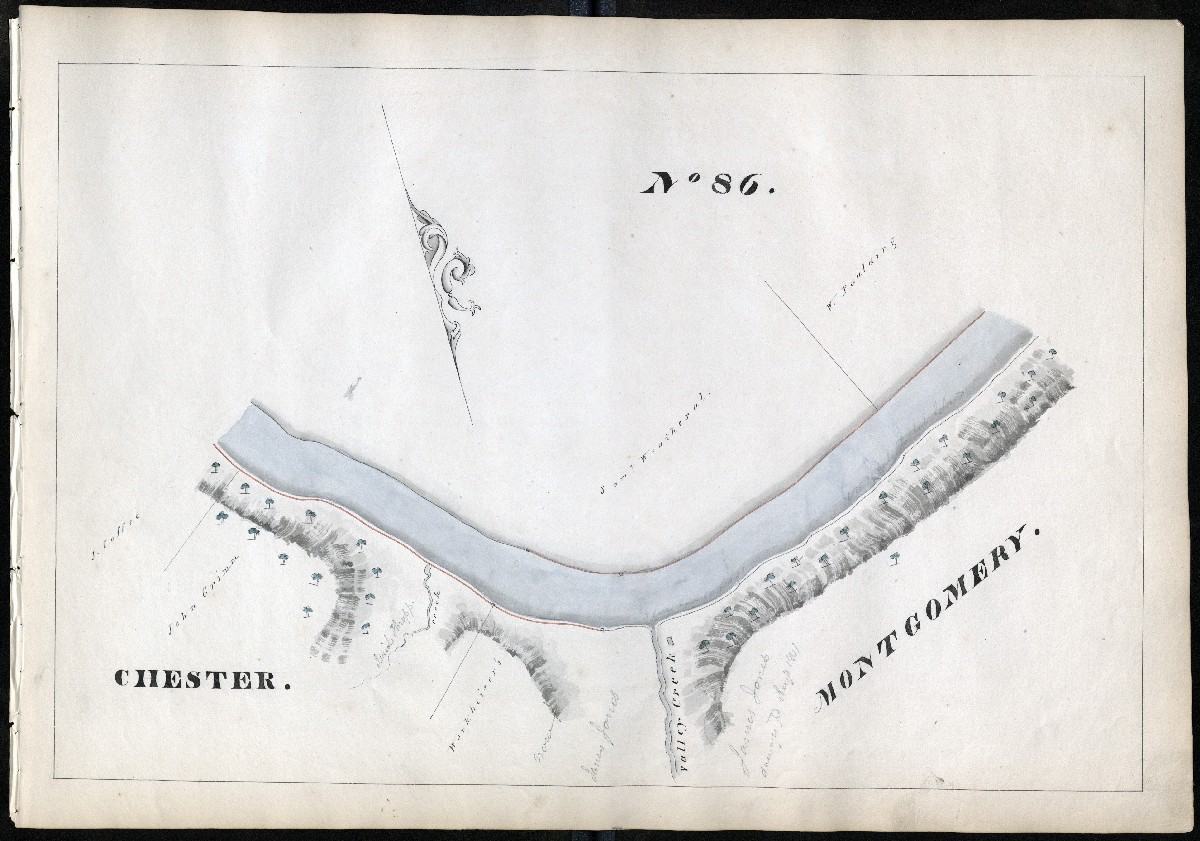

Montgomery County, Miles 86 – 100

MILE 86

MILE 87

MILE 88

MILE 89

MILE 90

MILE 91

MILE 92

MILE 93

MILE 94

MILE 95

MILE 96

MILE 97

MILE 98

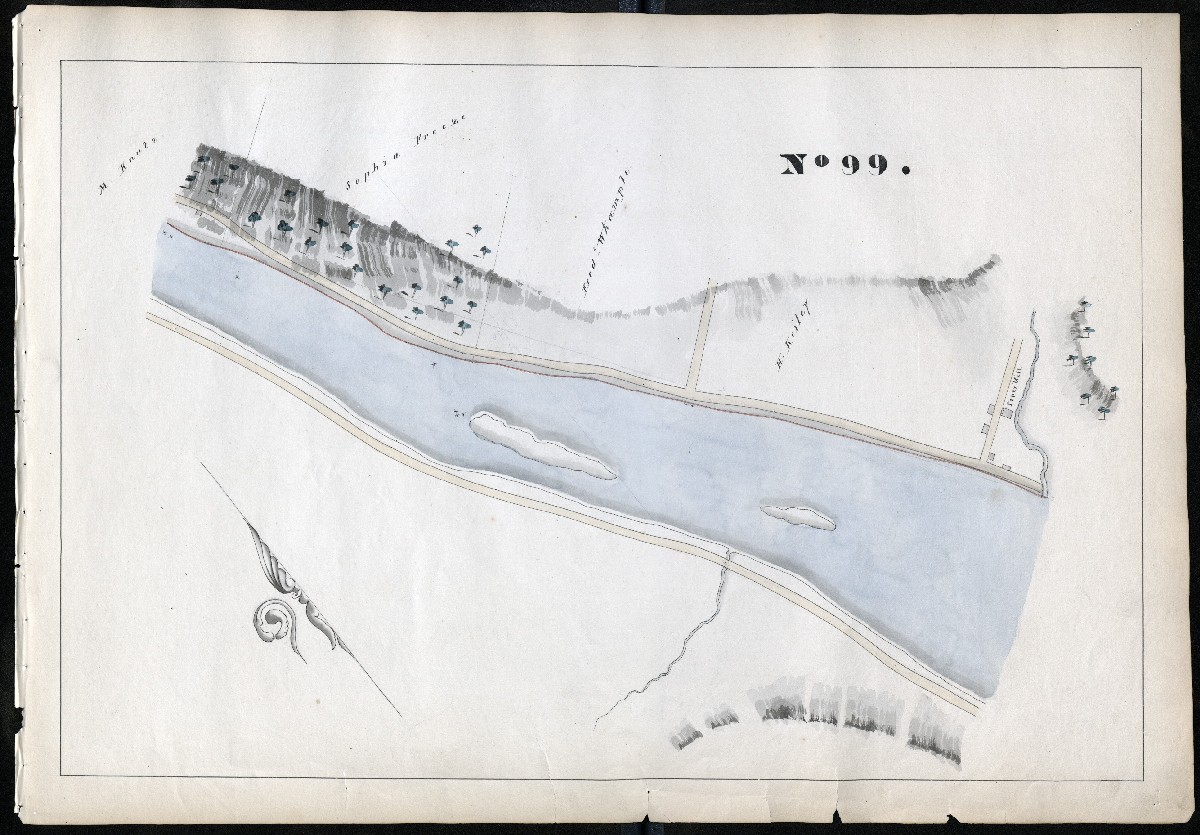

MILE 99

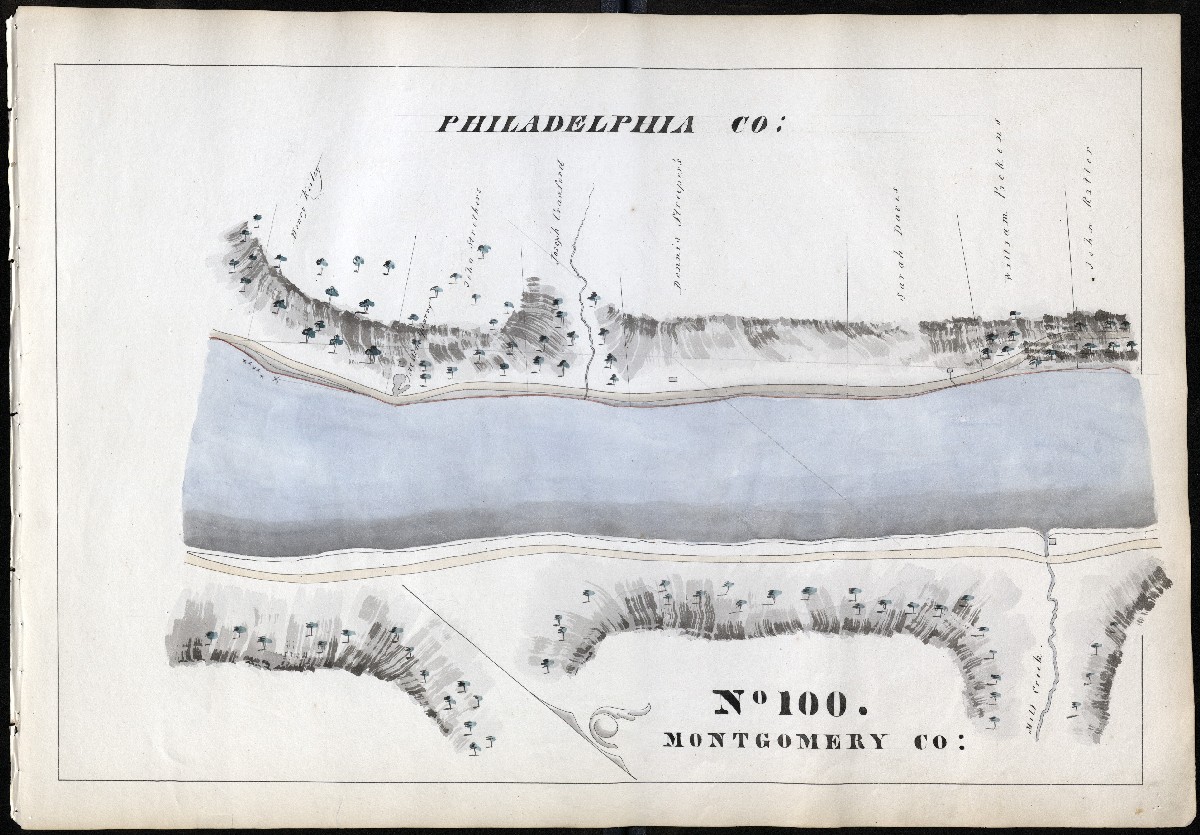

MILE 100

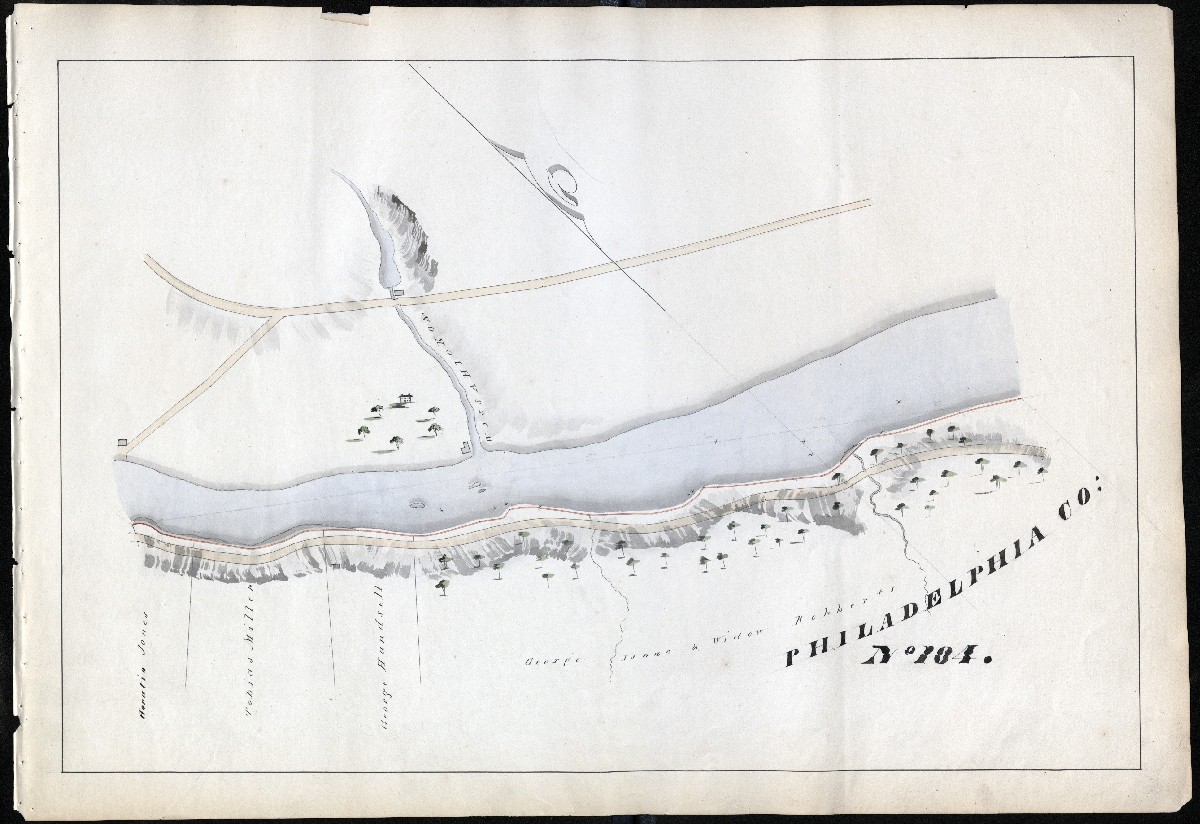

Philadelphia County, Miles 101 – 108

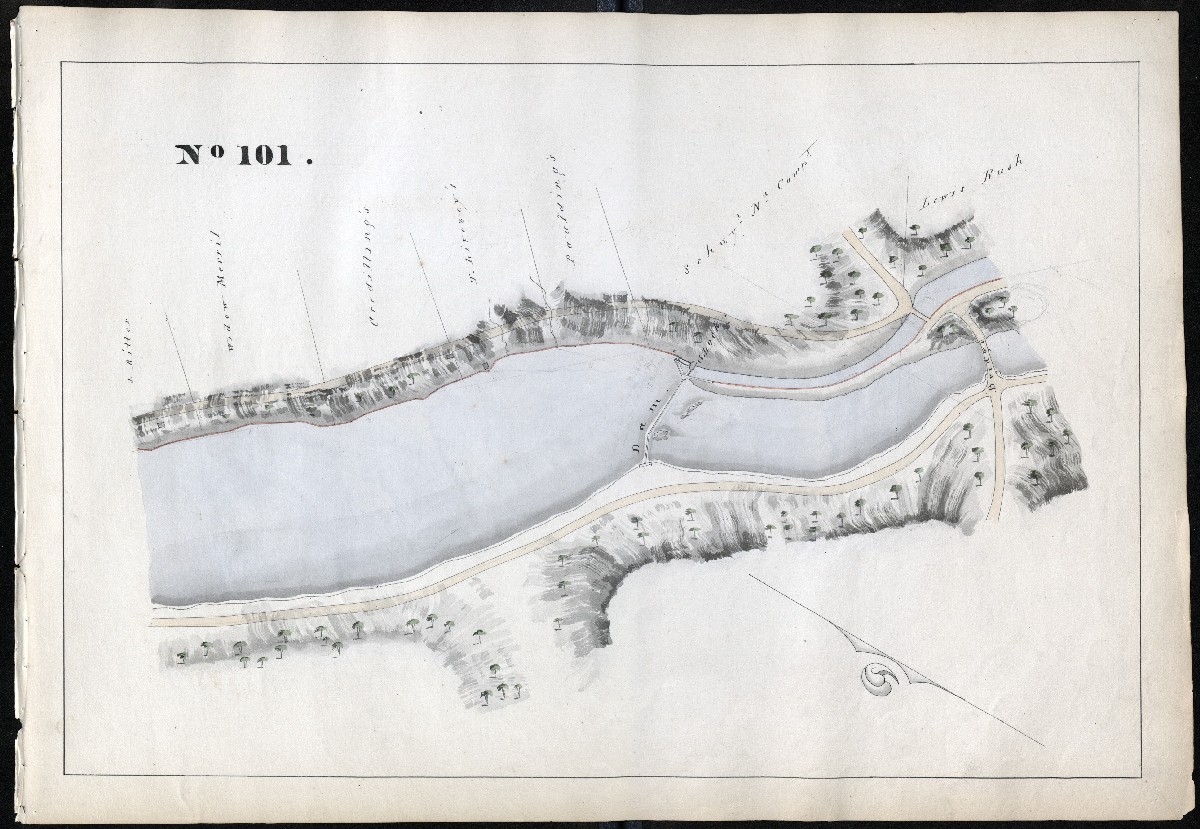

MILE 101

MILE 102

MILE 103

MILE 104

MILE 105

MILE 106

MILE 107

MILE 108

Return to Top of Page