An Excerpt from

The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition, Held In Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of American Independence.

by James D. McCabe

Philadelphia, Pa. : The National Publishing Company, 1876

To illustrate this text, I have added a variety of images, some of which I hope are new to at least some readers. As is the case with many posts from the old PhillyH2o website (the predecessor of WaterHistoryPHL), the McCabe book has since been scanned and posted online in its entirety. One version which – unlike many online books – includes all the illustrations can be found on the Internet Archive.

In the book, the waterfront tour continues up the Schuylkill River, but you will have to read that section on your own. It begins on page 133.

The Water Front.

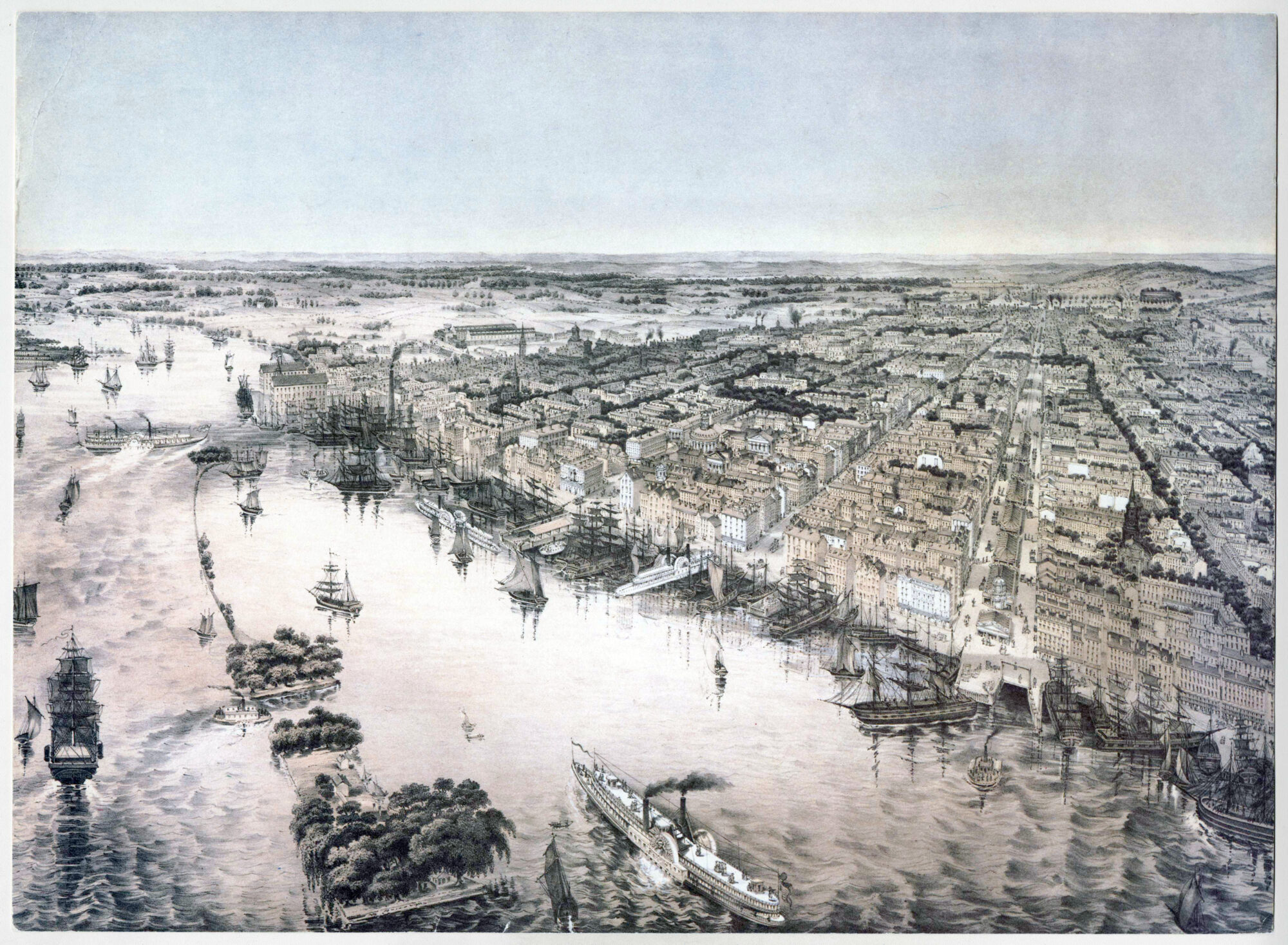

The plateau on which Philadelphia stands is washed on three sides by the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, which give to the city all the advantages of a great commercial seaport. Along the Delaware shore there is always to be seen a forest of masts, representing the shipping of every nation on the globe. The visitor to Philadelphia should by no means omit an opportunity, to view the city from the Delaware river, as from no other point can he as perfectly acquire a correct idea of the vast commerce which yearly enters and leaves this port. An excellent plan would be to engage a boat at Tacony, descend the river to the mouth of the Schuylkill, and ascend that stream to the exhibition grounds.

Starting from Tacony, the suburb of Bridesburg is soon passed, and then, turning a bend of the river, the visitor finds himself opposite Port Richmond, the coal-shipping depot of the Reading Railroad Company. This vast depot is one of the “sights” of Philadelphia, and is the most extensive in the world. It comprises 21 shipping docks, with an aggregate length of 15,000 feet, and accommodations for 250 vessels and boats. The shipping piers are 23 in number, and their aggregate length is 4-1/4 miles. They are provided with 10-1/2 miles of single track, and in addition to this are connected with each other and with the main line of the road by 22 miles of track. The cars, loaded with coal at the mines, are brought direct to this depot, and are run out on the shipping piers. By means of trap-doors in the floors of the cars the coal is emptied into schutes [sic] 169 feet in length, which convey it directly into the holds of the vessels to be loaded. About 2000 men are employed here, and the daily shipments of coal amount to 30,000 tons. The piers have a storage capacity of 175,000 tons. The company at present employ six fine iron steamers for the transportation of coal from Port Richmond to other points, and intend to increase this number to fifty. Several hundred other vessels are employed in this trade.

Opposite Port Richmond is Treaty Island, a spot dear to the hearts of Philadelphia sportsmen.

A short distance below Port Richmond are the shipyards of William Cramp & Son, said to be the most extensive establishment of its kind in the United States. A number of vessels were built here for the navy during the civil war, among others the New Ironsides. The four iron steamers of the American Line, plying between Philadelphia and Liverpool, were also built here.

Below these shipyards rises the standpipe of the Delaware Water Works, and beyond this is a region devoted to rolling mills, iron foundries and forges; and beyond these still, occupying the river front from Laurel to Noble street, is a succession of lumber yards, where an immense business in all kinds of lumber is annually transacted. Large quantities are shipped to South America and the West Indies. Immediately below Noble street are the freight depots and piers of the North Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads.

Below Noble street the long line of foreign and coastwise shipping begins, and stretches away for several miles down the river. Immediately opposite this part of Philadelphia, and separated from it by the Delaware, is CAMDEN, the sixth city of New Jersey. It is but a suburb of Philadelphia, with which it is connected by six lines of steam ferries. The time occupied crossing the river is five minutes.

In the middle of the Delaware, opposite Market street, is Smith’s Island, a noted pleasure resort. Immediately south of it, and separated from it by a narrow channel, through which the Camden & Amboy Railroad ferry boats pass, is Windmill Island, also a pleasure resort.

At the foot of Christian street and Washington avenue are the docks of the American line of steamers to Liverpool. In the rear of these docks is the enormous Elevator of the Pennsylvania Railroad, with a capacity of half a million bushels of grain, and every facility for prompt and economical shipment.

Immediately adjoining these docks is the Old Navy Yard, covering a tract of eighteen acres. It was purchased by the government in 1801 for $37,500, and was sold about a year ago to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company for about $2,000,000. Some of the finest vessels in the navy were built here. The navy yard has, since the sale, been entirely transferred to League Island. The Pennsylvania company intend to fit up the old navy yard as their principal terminus on the Delaware. This road is a large stockholder in the American line of steamers, which vessels lie at its docks and receive and transfer passengers and freight from and to its cars. By this system all breaking bulk of freight from distant points is avoided, there being but one reshipment, from the cars to the steamer, necessary.

At Greenwich Point, at the foot of Packer street, are the coal wharves of the Pennsylvania Railroad, second only in extent and the amount of business transacted at them to those of the Reading road at Port Richmond.

Just above the mouth of the Schuylkill is League Island, now occupied by the United States as a Navy Yard. The island was presented to the government by the city of Philadelphia. It covers an area of 600 acres, and when the extensions in contemplation are completed, will have a frontage of nearly three miles on the Delaware, with an average depth of water of twenty-five feet. Machine shops, and all the establishments necessary to the purposes of a great naval station, have been constructed or are in course of construction. The back channel is for the use of monitors, a large number of which are here laid up in ordinary. The advantages of League Island as a naval station are thus summed up by the Secretary of the Navy, in, his report for 1871: “A navy yard so ample in its proportions, in the midst of our great coal and iron region, easy of access to our own ships, but readily made inaccessible to a hostile fleet, with fresh water for the preservation of the iron vessels so rapidly growing into favor, surrounded by the skilled labor of one of our chief manufacturing centres, will be invaluable to our country.”

Just below League Island is Mud Island, on which stands old Fort Mifflin. This work was begun at the outbreak of the Revolution, and consisted then of an embankment of earth. It was known as the “Mud Fort.” Upon the occupation of the city by the British in 1777 it became necessary to capture the defences on the Delaware, at Mud Island and at Red Bank, on the New Jersey shore, in order to open communication between the British fleet and the city. Could these works have been held by the Americans the enemy must have evacuated the city. On the 22d of October, 1777, Lord Howe opened a tremendous cannonade upon Fort Mifflin from his fleet, and at the same time a picked force of twelve hundred Hessians was sent to storm the works at Red Bank.

The latter attack was repulsed with a loss of four hundred men, and the Hessian commander, Count Donop, was slain. In the attack upon Fort Mifflin the British lost two ships, and the remainder were more or less injured by the fire of the American guns. Soon after this repulse the British erected batteries on a small island in the Delaware, and on the 10th of November opened a heavy fire upon Fort Mifflin from these works and their fleet. The bombardment was continued until the night of the 15th. Fort Mifflin was literally destroyed, and on the night of the 16th was evacuated by its garrison. On the 18th the works at Red Bank, on the Jersey shore, were abandoned. The British removed now the obstructions from the river, and their fleet ascended to Philadelphia. [PAGE 133] The present work was constructed after the close of the Revolution, and is strongly armed.