Since 1801, when Philadelphia began providing water for the domestic use of its citizens and to use for street-cleaning and firefighting, the region has suffered through many droughts that have drastically reduced the flow in the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, from which we get our supply. But no matter how prolonged these droughts, and how low the river levels have fallen, the Philadelphia Water Department has always managed to keep the water flowing through its pipes. During some droughts, especially in recent years, non-essential uses—including washing cars, watering lawns, and water-intensive industrial processes—have been curtailed. But water has always been available for its essential “public health” purposes: to maintain human hydration and cleanliness.

The only times Philadelphians ever suffer without water—sometimes a day or so, other times only a few hours—is when water pipes (also called water mains) break. Not every break causes a stoppage of flow, and most stoppages only affect small areas of the city for a limited amount of time. PWD has more than one way to pipe water to any particular neighborhood, so when a break cuts off one route, it usually doesn’t take long for water to be rerouted through another pipe.

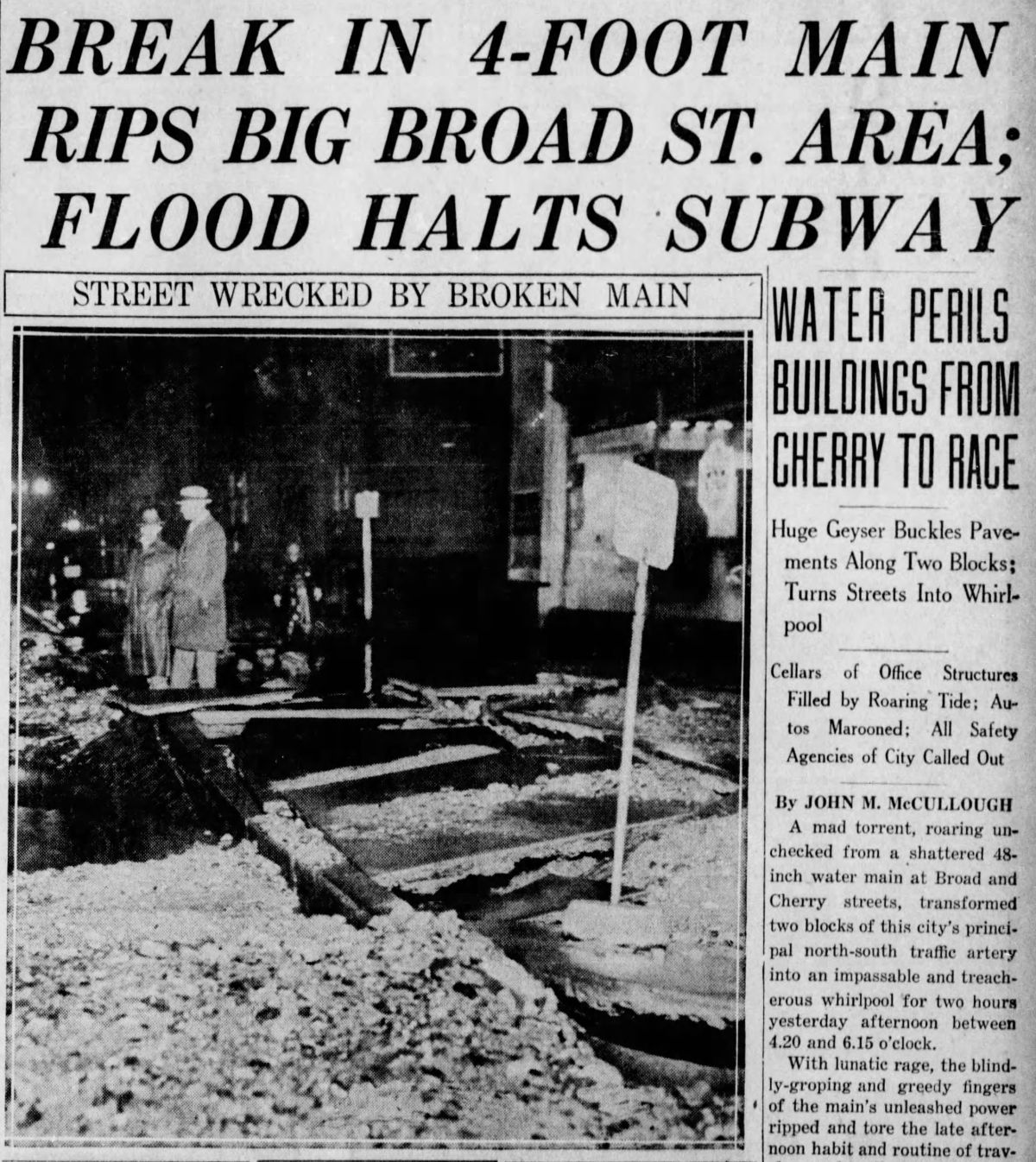

In the PWD Historical Collection, we have a 1920s scrapbook of water-related newspaper articles that provide an interesting perspective on living without water.

“Water Main Break in West Philadelphia – Early Morning Burst Forces Hundreds to Go to Work Unwashed – Coffee Pots Are Useless,” read a headline in the Public Ledger on November 5, 1921. The report continued: “There was no water for washing or shaving or to fill the coffee pot this morning in a large area of West Philadelphia, as the result of a burst water main at Fifty-second and Brown streets.” Residents “had to go to work with dirty hands and faces,” and drink hot milk that morning instead of coffee. The break occurred at 5:30 A.M., and by that evening water service was restored.

A December 12, 1922 story in the Public Ledger about “twelve hours of enforced drought resulting from a break in a thirty-inch water main” stated that “the much-harassed householders who last night were deprived of their water when most homes were getting ready for dinner had a short supply in time for breakfast.”

Even when a 60-inch main break caused a “water famine” for about half the city of water on January 10, 1923, the problem didn’t last more than a day. More of a concern from that break (and many others before then and to this day) were the buildings that were flooded before the affected pipe was located and the flow of water shut off. The Inquirer reported that the cellars of many houses were flooded, along with ten factories in Frankford. These business had to be shut down temporarily, resulting in the loss of a week’s pay for thousands of employees.

Reporters then called these brief stoppages “water famines.” This sensational, attention-grabbing term is laughable today, when large cities, their reservoirs running dry, are faced with true water famines; and when many places around the world have never had reliable sources of potable water.