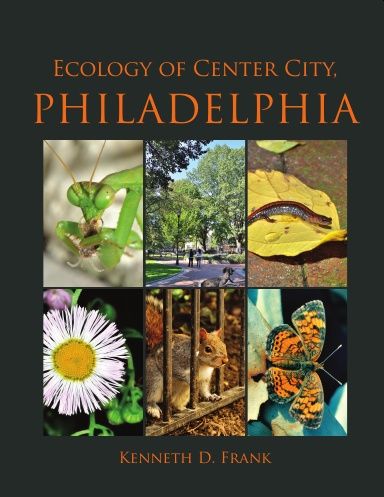

The following essay is an excerpt from Kenneth D. Frank’s illuminating book, Ecology of Center City, Philadelphia, published in 2015 by Fitler Square Press. Frank, a 40-year resident of Center City, writes about the plants and animals that thrive in downtown Philadelphia, many of which may surprise you. You can view or download a digital copy of the book here.

A retired physician, Frank is also the author of Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi and More, published in 2022 by Columbia University Press. About this book reviewer Kevin J. Gaston, of the University of Exeter, wrote:

“Cities are renowned as hot spots of human diversity. This book demonstrates that although less well known, this is equally true of biodiversity. Here this is viewed through the unusual lens of reproductive diversity–the variety of means by which organisms perpetuate their lineages. It is a volume filled with insight and lots of natural history nuggets, and it is beautifully illustrated. I imagine that most readers will find ‘I didn’t know that’ moments throughout.”

AT FIRST GLANCE, downtown Philadelphia, commonly called Center City, seems to embody what Bill McKibben projected in his book The End of Nature: complete subordination of Earth to people. Here every parcel of land is zoned, and each zone is identified with a code specifying permissible development and use. Michael L. McKinney, at the University of Tennessee, pointed out that plants and animals in central core districts of big cities tend to be similar—mostly cosmopolitan species, products of ecological homogenization. He blamed this uniformity on the dedication of downtowns everywhere to serving just one species: human beings.

People do dominate the landscape of Center City, and exotic organisms are common here, especially in soil; but the ecology of Center City is largely hidden. While buildings and pavement cover the landscape, wild plants and animals, including native species, thrive—albeit in small fragments such as in pavement cracks and courtyards, or underwater or in darkness, or as tiny, taxonomically obscure organisms. While Center City’s mass of concrete and asphalt epitomizes habitat destruction, it also exemplifies habitat creation, represented by dry vertical walls—ideal nesting sites for black-and-yellow mud daubers, for example.

Ecological disturbance in Center City has benefited some urban populations at the expense of others. Water pollution benefited the brown bullhead (a pollution-tolerant native catfish) at the expense of its enemies, which were intolerant of it. Municipal streetlamps nurtured bridge spiders that ate insects attracted to the light. Some populations reaped benefits at no cost to others. Disruption of migratory behavior in Canada geese opened urban and suburban territory, including Center City, as breeding grounds.

Center City is ecologically dynamic. Populations of the ailanthus silkmoth exploded in the 19th century, only to go locally extinct in the 20th. Yellow jackets that just over a decade ago swarmed around outdoor food and drink have mysteriously vanished as table pests. Red-tailed hawks once absent here have proliferated, while cries of nighthawks, once heralding summer nights, have gone silent. Numbers of house sparrows and starlings in Pennsylvania are declining after a century of superabundance.

In the tidal Schuylkill River, populations of channel catfish and flathead catfish have surged, while brown bullhead catfish have disappeared; American shad have returned, and the northern snakehead (an exotic predatory fish) has just moved in. Mugwort, absent in Philadelphia’s early 19th-century flora, is now one of its most common wild herbaceous plants. Japanese mazus, a denizen of sidewalk cracks in old residential sections of Center City, is also relatively new. Ailanthus trees, imported here at the end of the 18th century and naturalized in the 19th, face an uncertain future in the 21st: A fungal epidemic is destroying stands of them in a Pennsylvania state forest 210 kilometers to the west.

While communities of plants and animals in Center City have been transformed, so has its human population, increasing in number and wealth. New construction is increasing the height and density of buildings. These physical and demographic changes present Center City’s wild inhabitants with new demands and opportunities, maintaining pressure for ecological change.

Political and cultural shifts have driven ecological change in Center City. Action to protect the environment has brought back to Center City plants and animals once locally extirpated. Commerce and transportation will continue to introduce exotic strains and species into Center City, enabling genetic mixing among strains once geographically isolated and applying the selective pressure that catalyzes evolution. Center City does not epitomize the end of nature; on the contrary, it exemplifies nature’s resilience.