Chapter 2 of The Water Works of the City of Philadelphia: The Story of their Development and Engineering Specifications

Compiled in 1931 by Walter A. Graf (Staff Engineer, The Budd Company, Philadelphia), with the assistance of Sidney H. Vought and Clarence E. Robson. This online version was created from an original volume at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Catalog No. WZ 23591 (4th Fl. Folio).

Walter Graf History Home Page

(With Notes on the Text, Preface, and Acknowledgements)

Reading the Preface will give a quick overview of the beginnings and expansion of the Philadelphia water system.

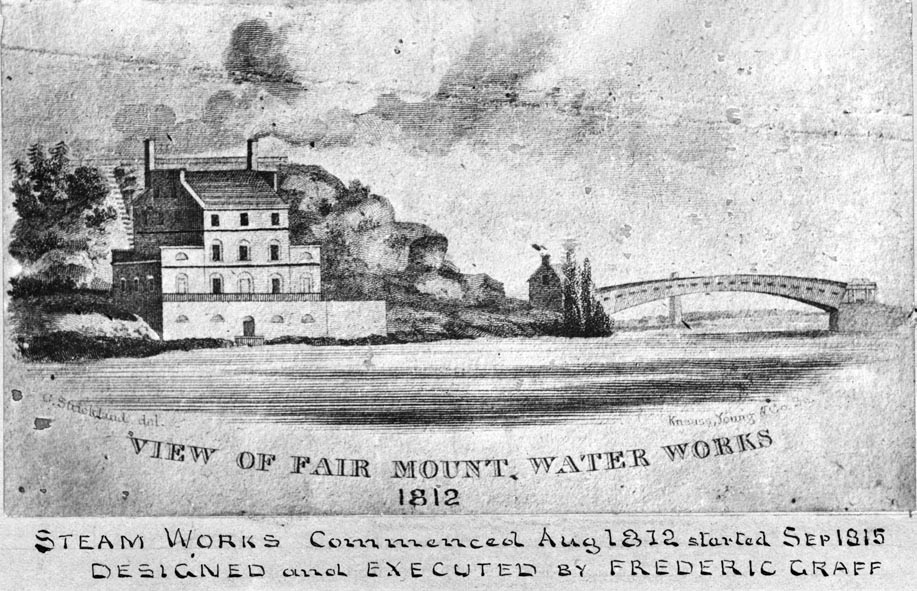

THE INEFFICIENCY AND small capacity of the engines and pumps rendered the Centre Square and the Schuylkill stations inadequate for the growing population of the city, and led Councils to develop plans to provide for a better system of water supply. On December 18, 1811 Councils adopted the plan of John Davis and Frederick Graff, for a new and larger steam works on the Schuylkill at Fairmount, (Fairmount was deemed a better location), and for abandoning the old Schuylkill station. Reservoirs of sufficient capacity to accommodate the city with a constant supply of water were to be located on the summit. These works were commenced August 1, 1812 and in operation September 7, 1815. The Schuylkill station was then shut down. (FIGURE 11)

A substantial stone building was erected at the foot of Fairmount Hill. The building housed a Boulton and Watt steam engine, of 44-inch cylinder and 72-inch stroke, operating a vertical double acting pump of 20 inches diameter and 72 inch stroke, raising water through a 16-inch iron main, 239 feet long into a reservoir, 102 feet above low water in the Schuylkill River.

This Boulton and Watt engine, a low pressure condensing engine, was somewhat similar in type and design to the engines of the Centre Square and Schuylkill works, with the exception that the beam, the flywheel arms and the shafts were made of cast iron. This was a distinct improvement over the former wooden constructions. The larger castings for this engine were made by Samuel Richards at Weymouth Blast Furnace, in New Jersey, because there was no furnace available in Philadelphia large enough to make them. The smaller castings were made at the Eagle Works foundry situated a short distance from Fairmount, at William (now 24th Street) and Callowhill Streets.

This engine was equipped with a boiler having a cast-iron case and vertical flues or heaters of wrought iron. Upon trial this station pumped approximately 2,116,000 gallons in 24 hours on 2½ to four pounds steam pressure with a fuel consumption of seven cords of wood.

The reservoir, completed in 1815, was located upon Fairmount hill on the east side of the engine house within a few hundred feet of the pumps, and had a capacity of approximately 4.8 million gallons. The water was conducted from it to the distributing chest at Centre Square by six lines of hollow wooden logs, five of six inches inside diameter and one of 4½ inches inside diameter. These lines were laid along the bed of the old Union Canal to Broad Street and down Broad Street to the Square, a total distance of 9,337 feet.

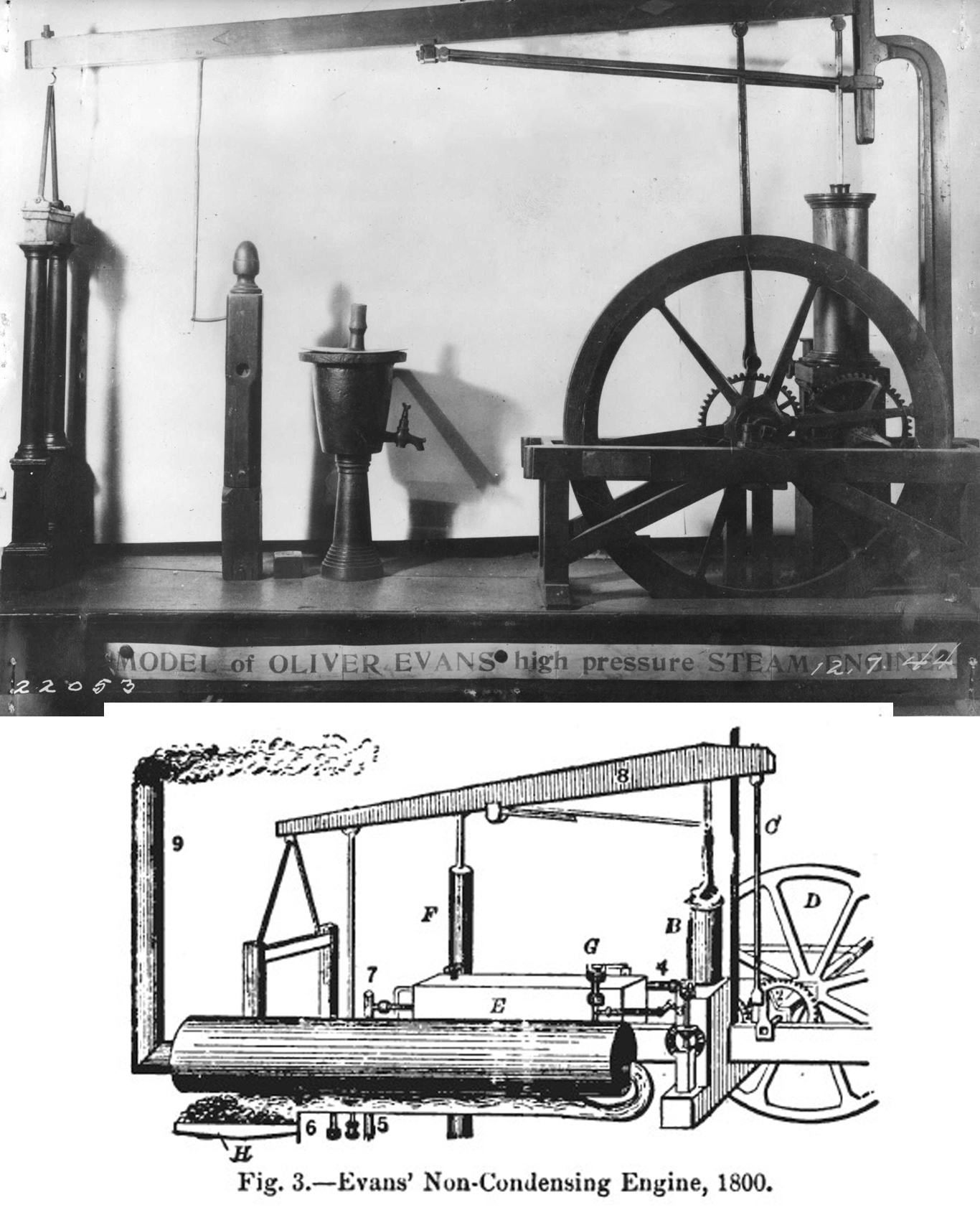

Previous to the erection of the water works pumping station at Fairmount, a contract had been made by the Watering Committee with Oliver Evans for a high pressure steam engine. Evans had been studying the possibilities of using high pressure for a long time. During 1799 or 1800, he began constructing a steam carriage and finding his steam engine differed in form, as well as in principle, from those in use at that time, he secured patents and applied it to the operation of mills. This was probably the first steam engine ever constructed on the high pressure principle, and the merit of the invention seems to belong to Evans.

The steam cylinder of the engine built by Mr. Evans for the Philadelphia Water Works was 20 inches in diameter with a 60-inch stroke. It had rotating steam valves, worked by bevel gear wheels, driven from the main shaft; the beam was made of wood and was suspended at one end upon vibrating standards; the piston rod was attached to the other end of the beam. The engine is depicted in FIGURE 12.

The boilers were probably of wrought iron construction, 24 feet long, 30 inches in diameter and four in number, in which steam was at time raised to 220 pounds to the square inch. Such high pressure caused two explosions.

On May 15, 1817 this engine was submitted to a test. In a run of 24 hours at 22 revolutions per minute, under a steam pressure of 194 pounds to the square inch, 13 cords of oak wood were consumed, and 3,750,000 gallons of water pumped into the reservoir. On December 15, 1817 this engine started regular operation.

In the year 1818 the length of all the wooden pipes in use was approximately 32 miles. Their continued bursting gave the Water Department much concern and they seriously considered using cast-iron pipe. An experiment with iron pipe in Water Street in 1804 had been unsatisfactory. However the attention of those directing the water works was attracted to the reports on the use of iron water pipes prepared by a Mr. J. Walker, of London, who was reputed to be an authority on the subject. He brought out so many excellent points that it was decided to try iron pipes again, and to buy the first cast-iron pipe in England because the then existing industries in the United States were not equipped to manufacture cast-iron pipe or conduits. The imported pipe was laid from Fairmount to the junction of Chestnut and Broad Streets. The cast-iron industry was later developed in the United States.

It was estimated in 1815 that up to the date of completion of the Fairmount Station, Philadelphia had spent on its centralized public water supply system around $1 million. This was an enormous expenditure, and yet it cannot be said that this was a loss to the city, because these early experiments, although crude, were foundation of the high degree of efficiency realized in later years. In those days the character of the city was strengthened by the improvement in its sanitary condition and the eventual adequacy of its pure water supply stimulated its growth as a residential city.

The population of the city was constantly growing and there was a constant increase in the difficulty and expense of supplying a sufficient quantity of water with the machinery then in use. This state of affairs kept the City Councils constantly on the alert for a cheaper and more copious supply of water. The estimated cost of running the Oliver Evans engine, pumping an average of 2.3 million gallons per day, totaled $30,858.75 per year or $36.60 per million gallons pumped into the reservoir. This high cost encouraged the thought of deriving water power from the Schuylkill. As early as 1807 deriving water power from the Schuylkill River had been considered. Upon April 9th, 1807 the State of Pennsylvania granted a charter to Mr. James Kennedy, giving him the rights and privileges of erecting a dam and locks at the at the Falls of the Schuylkill, for water power development, but with a clause inserted which gave the city the right to purchase Mr. Kennedy’s improvements at any time the city desired to use them.