NOTE FROM ADAM LEVINE This excerpt, from the report of Chief Engineer William Ludlow, provides an overview of the failed attempts to keep the Schuylkill River’s Fairmount pool – from which 80 percent of the City’s water was withdrawn- free from pollution. Of special interest to me is the discussion of sewage pollution, and the dangers it posed to the health of the population. Even though the connection between raw sewage in drinking water supplies and certain intestinal diseases was known at this time, it took the city more than 20 years – and many thousands of deaths from annual typhoid fever epidemics – to do anything about it. The course chosen was not to keep pollution out of the rivers, or to seek a new, cleaner water supply, as several commissions of experts recommended in the latter half of the 19th century. The city chose to filter the sewage-laden river water, beginning in the early 1900s, and then took the further step of chlorination beginning in 1912. These steps greatly reduced illnesses from typhoid and other water-borne diseases. Unfortunately, the health of the rivers continued to decline for another 40 years, until the implementation, in the early 1950s, of full-scale treatment of the city’s sewage.

The Present Water Supply

Excerpt from the Annual Report of the Chief Engineer [WIlliam Ludlow] of the Philadelphia Water Department for the year 1884.

The total quantity of water: pumped and delivered in the mains during the year 1884 was 25,495,179,353 gallons, an average of 69,658,969 gallons per day, which, reckoning the population at 960,000, is equivalent to 72-1/2 gallons per day for every man, woman and child in the city. The largest amount pumped in anyone day was 95,686,444 gallons on May 28, 1884, and the least was 46,163,058 gallons on February 10, 1884.

The Kensington pumpage, for reasons sufficiently set forth in the last Annual Report, has been reduced as much as possible, and when certain modifications of the mains which are now in progress shall have been completed will be entirely suspended, after which the Fairhill basin on Lehigh avenue will be supplied from the Schuylkill.

With the exception therefore of the comparatively small quantity taken from the Delaware River at Lardner’s Point for Bridesburg, Frankford and their vicinity, and the still smaller quantity derived from the springs at Chestnut Hill, the water supply of Philadelphia is pumped from the Schuylkill River at four principal stations, viz: Fairmount, Spring Garden, Belmont and Roxborough.

The Roxborough Station takes its water from above Flat Rock Dam and by means of the Roxborough and Mt. Airy Basins, respectively 365 and 362 feet above City Datum, with an auxiliary pumping station at each basin, supplies Roxborough, Manayunk, the Falls of Schuylkill, Germantown, Mt. Airy, and that part of Chestnut Hill south of the Germantown Pike.

The Belmont Station on the West bank just below the Columbia Bridge raises the water to the Belmont Basin, 212 feet above City Datum, for the exclusive supply of West Philadelphia.

The Spring Garden Station, on the East bank just above the Girard Avenue Bridge, through the Spring Garden and [PAGE 39] Corinthian Basins (120 feet above City Datum) supplies the city below South Street and from Vine to Spring Garden Street, and by direct pumpage without a reservoir, supplies the city north of Spring Garden. This Station will also be charged hereafter with the supply of Kensington and the vicinity, through the Fairhill Basin, 114 feet above City Datum.

The Fairmount Station, situated at the dam, through the Fairmount Basins (94 feet above City Datum) supplies the old city from Vine to South between the two rivers.

Spring Garden and Fairmount supplement each other from time to time, the former delivering into the Fairmount Basin when the low stage of river restricts or stops the action of the turbines, and the latter pumping to the Corinthian Basin when the river is up and the Fairmount Basins full.

Of the total amount used in the city these four Schuylkill Stations pump 80.59 per cent., and the three lower ones, viz: Belmont, Spring Garden and Fairmount, drawing from the middle and lower end of the Fairmount Pool, pump 80.06 per cent.

From these statements two leading facts are apparent:

First. That the supply of the city is practically dependent upon the maintenance of the two dams, especially that at Fairmount since, should they give way, the Pool would be drained and the Stations left high and dry.

Secondly. That the quality and wholesomeness of the supply are dependent upon the condition of the Schuylkill in general, and in particular of the Fairmount Pool which constitutes in effect the main storage or subsiding reservoir of the city.

There should be no danger of the failure of the dams, since from time to time in the past they have been examined and repaired, and the deterioration due to gradual decay and the destructive action of ice and water have been amended. Nevertheless it must be recognized that the materials of which the dams are constructed are perishable and that at some time in the future it will be necessary to rebuild them. [PAGE 40]

Aside from the obligations of the city through its contracts with the Schuylkill Navigation Company to maintain the slack water navigation to Manayunk, and whatever may be hereafter adopted as the source of the future water supply, the Fairmount Pool is too beautiful and valuable a portion of the Park to warrant its degradation or abandonment. The dam will therefore no doubt be maintained in perpetuity, and when opportunity offers it should be rebuilt with imperishable materials and so converted into a permanent structure.

The second consideration, viz: that relating to the quality of the water, is far more urgent, since upon the wholesomeness and potability of the domestic water supply depend in great measure the well-being and comfort of the individual and the general health and prosperity of the community. Among all the varied and complex conditions of modern municipal existence, there is none excelling in vital importance the integrity of the water supply, unless exception should be made of its natural continuation and supplement the system of drainage, and there is no problem in city engineering giving rise to more solicitude and thought, and demanding more earnest attention and wise prevision.

There is scarcely a city in the civilized world that has not sooner or later been compelled to confront this problem and to seek heroic means for its solution. London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Glasgow, Edinboro’, Liverpool, Manchester and many smaller European cities; in our own country, New York, Brooklyn, Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, with numerous others, impelled by the increasing contamination and insufficiency of their local supply, have bravely faced their respective difficulties, and by large and in some cases immense expenditures, under the guidance and direction of the ablest engineering and sanitary intelligence and by every scientific aid which they could command, have labored with courage and persistence to secure and maintain that purity and abundance of water supply which is universally recognized as a vital necessity.

Philadelphia began well and acted as pioneer for them all. [PAGE 41] She established the first public water supply in this country, and by suitable modifications and enlargements from time to time, strove to keep pace with that rapid material development which resulted from her favorable conditions and the enterprise and intelligence of her citizens. The Schuylkill in the earlier days furnished an abundance of wholesome water, and even supplied the power to drive the wheels by which it was drawn from the river and delivered into the distributing mains.

But as the population increased and the banks of the river became the seat of new industries, the pollution of the water proportionately augmented. The coal and iron industries came into existence in the upper valley, railroads were built, communities multiplied and prospered, and within the present city limits mills and manufactories were established which discharged their waste matters into the stream.

This condition of affairs had been anticipated at an early day and steps had been taken which it was supposed would be effective to guard against it. The final agreement made in 1824 between the city and the Schuylkill Navigation Company exacted that in making sale or lease of the water power from Flat Rock Dam the Company should introduce provisions forbidding the discharge into the river of dye stuffs or any noxious, fetid or injurious matters, and that these should be confined in wells or repositories upon their respective premises.

Again in 1828 an act to protect the purity of the water supply was passed which forbade the casting of any “putrid or corrupt thing” or any noxious or offensive matters into the Schuylkill near the pumping stations. In 1832 (Act of February 7) more stringent provisions were enacted, as follows:

“If any person or persons shall willfully take, lead, conduct, carry off, or throw, or shall cause to be taken, lead, conducted, carried off, or thrown into that part of the River Schuylkill which is between the Dam at Flat Rock and the Dam at Fairmount, near the City of Philadelphia, any carrion or carcass of any dead horse, or other animal, or any excrement or filth from any slaughter-house, vault, well, sink, culvert, privy, or necessary, [PAGE 42] any offal or putrid or noxious matter, from any dye-house, still-house, tan- yard, or manufactory, or any matter or liquid calculated to render the water of said river impure, every such person, shall, for each and every such offence, forfeit and pay a sum not less than five dollars nor more than fifty dollars, at the discretion of the magistrate, to be recovered with costs of suit, in the same manner as debts under one hundred dollars are by law, recoverable, by any person who shall sue for the same, before any justice of the peace within the county of Philadelphia, one-half to the person prosecuting and suing, and the other half to the use of the mayor, aldermen and citizens of Philadelphia.

“No length of possession whatever shall be available to bar or prevent the correction or removal of any nuisance existing, or which may hereafter exist, at or near that part of the River Schuylkill which is between the Dam at Flat Rock and the Dam at Fairmount.”

Had these wise enactments, which have never been abrogated and are still the law of the Commonwealth, been enforced, much subsequent trouble and expense would have been avoided, but unfortunately, although the laws of decency were somewhat deferred to, the subtler laws of sanitation were unheeded. Out of sight was out of mind. Human nature is selfish, and nuisances multiplied until the growing pollution of the water occasioned loud complaints. In the report of the Water Department for 1853 the condition of the water is referred to as “unsatisfactory.”

In 1858 the Chief Engineer declared that objectionable drainage should be prevented, but the subject is treated with great caution. In 1860 the Department Report deals more openly with facts. The quality is still declared to be good, but complaints have been received of foul taste and smell. The evil quality of the Girard Avenue sewer and the large pollution from Dobson’s Run are referred to and it is boldly stated that Manayunk makes a common sewer of the river. The Chief Engineer quotes the laws against polluting the stream and urges their enforcement. Notwithstanding the increasing contamination the chemical analyses made from time to time still approved [PAGE 43] the water, and in 1862 owing, no doubt, to the comparatively crude methods of those days, were unable to discover any organic matter at all in the Schuylkill supply.

The supply from Kensington however, where catfish were cleaned near the mouth of Gunner’s Run, is rather heavily reprobated, and in fact had been absolutely condemned as early as 1856. In 1864 and 1865 the complaints multiply and grow more urgent. The report states that a large amount of objectionable matter reaches the pool. The river is made a general carrier of refuse and sewage; the sources of pollution are rapidly increasing and the salubrity of the water is threatened. There is ample legislation but no enforcement of the law.

In 1866 it is stated that within no equal period of time has the amount of impurities drained into the Schuylkill increased to such an alarming extent as during the past year, especially at Manayunk. The discoloration of the stream is plainly discernible at the Falls and sometimes at the Columbia Bridge. There is no doubt that constant deterioration is going on and the Chief Engineer adds the very reasonable remark that a city with the wealth and population of Philadelphia should at least be able to have pure water.

In 1867 the Mayor in his annual message urged the formation of a Commission of Hydraulic Engineers to investigate and report upon the supply, but the measure having passed one branch of Councils failed in the other, whereupon the Park Commission which had been created in 1867, for the avowed fundamental purpose of protecting the purity of the water supply, made examination and prepared a report in which it is concluded that with proper precautions to guard it from pollution by the interception of all sewage by due enforcement of the law and the construction of sewers on both banks the Schuylkill might be still relied upon for many years. The Water Department Report for 1868 renews reference to the Manayunk drainage and prints a comparative analysis of the supply of various cities, prepared by Prof. Chandler for the New York Board of Health: This analysis shows that in respect of the [PAGE 44] organic and volatile matters contained in 13 water supplies to American cities the Schuylkill water, which in earlier years had been noted for its general excellence, now stood precisely midway – six containing more and six less – and that the average of six London waters showed 1.15 parts of organic and volatile matters to 2.06 in the Philadelphia supply.

At about this time, however, the discrepancy which had long existed between the rapidly growing requirements of the city and the reservoir and pumping capacity of the Department plant, became a source of such overshadowing anxiety to its responsible head as to postpone the consideration of any less vital matter than the maintenance of the supply, and the procurement of more engines and storage facilities monopolized the attention of the Chief Engineer. With the reconstruction of the dam at Fairmount, the introduction of new turbines, the construction of the new West Philadelphia Works, the beginning of work upon the great East Park Reservoir and the planning of a new station for the supply of Frankford, his hands were certainly full.

In the report for 1870 is published a table of comparative analyses of Schuylkill water made respectively in 1842 and April 1870. It is not stated at what points the samples were taken and the spring rains generally have a favorable influence upon the quality of the water, but the fact is displayed that in the interval of twenty-eight years the amount of organic matter present in the water had increased over 700 per cent. In 1873 the Chief Engineer states that Manayunk “crowds the Schuylkill with factories,” and is even disposed to believe that the water will compare unfavorably with that of the Delaware within the city limits. In 1874 he is distressed by a threatened water famine due to lack of sufficient pumping plant and by a putrescent fermentation of the water in the Basin supplying the Kensington district. He refers to Manayunk as the main source of fouling the Schuylkill and to the contamination of the Spring Garden forebay by the open sewer in its immediate vicinity. [PAGE 45] He publishes an elaborate report by Dr. Cresson upon the quality of the Schuylkill, which is accompanied by analytical tables and much valuable information. The analyses showed that on February 9, 1872, the sewage in Fairmount forebay was 6.65 pounds in one million gallons, and this gradually increased until November when a large increment occurred, and later steadily increased until he says the water is occasionally charged with an amount of sewage exceeding that carried by the Thames at London and is at times totally unfit for use. On July 24, 1874, when, from the cessation of the flow of water over the dam, the objectionable drainage accumulated he found at the inlets to the Belmont, Fairmount and Spring Garden Stations respectively, sewage to the enormous amounts of 98.06,97.14 and 121.37 pounds to the million gallons, and therefore asserts that unless some precautions are soon taken to prevent the influx of this great amount of sewage of animal matter into our source of supply we may certainly expect to have our city visited by some epidemic scourge.

“The pollution of the Schuylkill river has been increased to such an extent as occasionally to class the water as ‘unwholesome’ and prompt measures should therefore be taken to relieve it of sewage containing fecal and decaying animal matter. The greatest proportion of these are now received from the streams draining into the pool of Fairmount dam. Preparations have been made to conduct that on the west side of the river below the dam by means of a sewer, and provision should at once be made for the sewage on the eastern shore.”

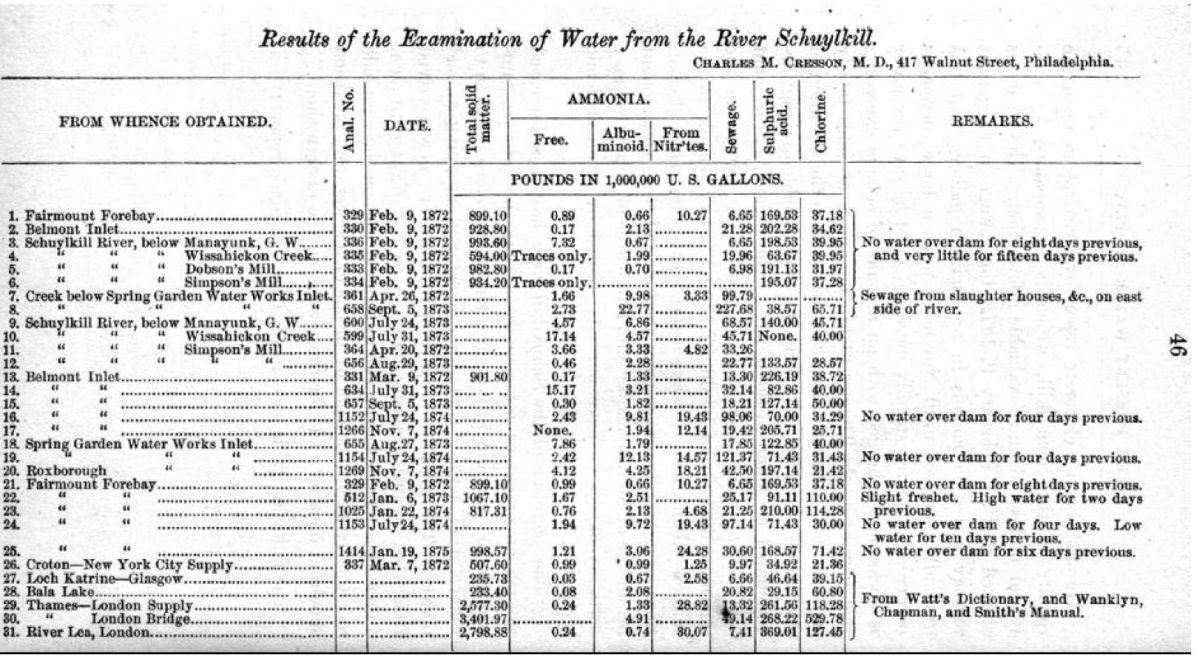

The following table accompanied Dr. Cresson’s report: [page 46]

[PAGE 47] The important features of these analyses, as regards the relative wholesomeness of the waters, are the amounts of the two ammonias. The great variability of the Schuylkill water at different seasons is well illustrated in this respect, and for purposes of comparison the water supply of Glasgow, derived from Loch Katrine, a nearly absolutely pure water, is highly instructive. The average amounts of free and albuminoid ammonias, the former indicating the recent oxidation of nitrogenous components, and the latter the presence of matters still capable of putrescence, in the waters of Loch Katrine are respectively 0.03 and 0.67, estimated as pounds in one million gallons. The Croton sample gives 0.99 and 0.99. The average of the Thames samples 0.24 and 2.33, while the average of the Schuylkill waters gives 3.13 and 4.64.

In October, 1875, a valuable and instructive report was submitted by a Commission of Engineers who had been called together by the Mayor in compliance with the ordinance of June, 1875, to consider the entire subject of the present and future water supply of the city. This Commission, whose organization was due to the alarming deficiency and dangerously augmenting pollution of the supply, was composed of eminent and capable men of the first rank in the profession. Their report deals largely with the question of pollution, devoting over fifty-six pages out of one hundred and forty-three exclusively to this subject, with numerous current references thereto in other portions. They state that the Schuylkill water, originally remarkably pure and wholesome, has been impaired by impurities accompanying the growth of population and the extension of industries, and that unless a remedy be applied it will ultimately be rendered unfit for domestic uses. The annual reports of the Department contain various recommendations for improving the quality, and in 1867 a special committee of the Park Commissioners made an able report devoted chiefly to the subject of the purity of the water and recommending measures for its protection. Nevertheless nothing has been done beyond the construction of a sewer to [PAGE 48] keep the sewage of West Philadelphia out of the pool. They invite particular attention to the able paper prepared by a distinguished member of the Commission on the pollution of rivers, and quote freely from it in the main report, in particular the following: “Testimony can be multiplied to almost any extent in support of the position that manufactory refuse renders water unfit to drink and we should condemn the admission of all filth without waiting for scientific reasons and demonstrative proof. That which is in any way offensive to the sight, taste or smell, and the sense of decency or propriety, has no more right to a part in the composition of our drinking water than those substances which are actually proved to be deleterious to health.” They note the diminished minimum flow of the Schuylkill from 500,000,000 gallons in 1816 to 245 or 250,000,000 gallons in 1874, and refer to the intimate relation of this fact to the subject of contamination since notwithstanding the large average volume of the stream, it is not adequate during periods of drought to correct the pollutions it receives, and as the inflow of polluting matter still continues, being steadily augmented in volume as the city grows and even in greater ratio, they recommend as a protection the construction of an intercepting sewer from above Manayunk, previously recommended by the Park Commission, or else that of a conduit to bring the purer water of Flat Rock to the main pumping stations below, the cost of either construction being estimated at about the same, viz., $1,000,000.

The paper by Col. Adams, to which special attention was invited, deals exhaustively with the general subject of the pollution of water supply, and traces the relation of disease thereto, especially of the intestinal disorders such as cholera, typhoid, dysentery and diarrhea.

The whole tenor of the paper, which quotes at length from the best authorities, is to the effect that no sewage should be permitted to reach drinking water,–that grounds for distrusting its purity are good grounds for its rejection if a better supply be attainable; and since it is impossible by any known [PAGE 49] method to restore water once contaminated by sewage to a condition of secure and reliable wholesomeness, the choice therefore lies between the absolute exclusion of sewage and the adoption of another source.

In the reports of the chemical examination of the water prepared for and submitted to the Commission, the authors state that “long continued experience of city life in various parts of the world has shown that water contaminated with animal refuse, such as the sewage of large cities, is fatal to health” and further “that it is not so much the quantity as the nature and condition of the dissolved organic matter that determine the goodness or badness of a water used as a beverage.”

From these preliminary statements it might be expected that the chemist’s report would contain an earnest remonstrance against the practice of using the Fairmount Pool as a cesspool and the receptacle for all descriptions of sewage and trade refuse, and present the most convincing evidence of this dangerous pollution, especially as the statement is made that offensive organic matter enters the Schuylkill in such quantities that in winter its presence is manifest even to so simple an investigator as a well constituted nose. It is therefore a surprise to find the opinion expressed that “the present water is good enough” and that the Schuylkill water in its mineral and organic content has now been shown to be “about as good a water as we might wish to find for a large city.”

Passing by without comment the curious thought that the inhabitants of a large and wealthy city need be less scrupulous in regard to the purity and wholesomeness of their drinking water than those of less populous and important communities, a singular discrepancy is obvious between the acknowledged facts and principles and the announced conclusions.

Investigation shows that these conclusions are mainly derived from an analytical table, printed on page 108 of the Report and here reproduced, exhibiting the amounts of free and albuminoid ammonias contained in the several waters under examination – these elements having been previously accepted [PAGE 50] in the report as affording indications of recent and existing sewage contamination and therefore of comparative purity.

Grains in 1000 Gallons

| Free Ammonia. | Albuminoid Ammonia. | |

| Fairmount | 1.17 | 1.76 |

| Belmont | 5.85 | 5.11 |

| Flat Rock | 7.31 | 5.12 |

| Perkiomen | 1.46 | 7.31 |

| Spring Garden | 17.50 | 8.75 |

| Delaware Basin | 25.74 | 11.70 |

| Bryn Mawr, Artesian Well | None | 1.75 |

| Thames River, London | 1.00 | 5.31 |

Assuming the quantities to be given as intended, inspection of this table reveals some peculiar features. It is not stated when the samples of Schuylkill water were taken, but it must be assumed that they were collected about the same time, as the well known variability of the river from the influence of rains and freshets would otherwise have rendered the comparison of no value.

As might be expected the Delaware Basin, taking water from the Delaware river near Gunner’s Run, makes the worst showing, and the Spring Garden sample, owing presumably to the influence of the sewer close by, the next. In albuminoid, Belmont and Flat Rock have slightly the advantage of the London average, while, singular to say, the Fairmount water is so far superior to all the others, as to be rivalled only by that from an artesian well in the country, four hundred feet in depth and beyond suspicion of sewage contamination. Upon this showing of the purity of the Fairmount sample is based the conclusion as to the satisfactoriness of the supply from the Schuylkill. Could this be really shown to be at all times true it is manifest that the other stations should be abandoned and the pumping plant, at whatever cost of re-arrangement, be concentrated at Fairmount, but to credit the statement, it is necessary to assume that a mysterious change takes place in [PAGE 51] the water within a short distance of the Fairmount Dam.

Furthermore since Flat Rock above the Pool is alleged to contain three times as much albuminoid and six times as much free ammonia as Fairmount at its foot, we are in effect called upon to believe, that in gathering the entire drainage of all Manayunk and the Falls, with four city sewers and numerous mills and ether establishments vomiting large quantities of the vilest waste matters into it, the river has actually purified itself and been converted into a fluid rivaling the well water of Bryn Mawr. It is needless to say that this is in contravention of known facts and conceivable possibilities, and in opposition to the Report of the Commission itself and other official reports on the subject.

Further comment is unnecessary, nor would so much space have been accorded this paper, were it not believed that serious harm has resulted from it in furnishing excuses for inaction in a matter of vital importance, and to point out the danger of drawing conclusions solely from occasional laboratory investigations of a stream, which in uncertainty of temperament and instability of constitution, is equaled only by the meteorological conditions which give it birth. In such a case its cycle of changes must be systematically followed and investigated, and its physical and sanitary conditions be carefully determined and studied, and laboratory deductions must confirm the observations of the sanitary engineer or be unhesitatingly set aside in favor of the readily ascertained and verifiable physical circumstances.

The Report of the Commission was not followed by the construction of an intercepting sewer nor abatement of the foul drainage into the Pool, and in the Water Department Report for 1876 the Chief Engineer returns to the charge. “Under the guise of pure limpid water, organic matters convey the seed of disease to the consumer.” As the Schuylkill is the nearest and most economical source of supply its purity must be restored and future pollution prevented by diverting all refuse; but apparently despairing of this he quotes from an [PAGE 52] eminent authority: “If water for domestic purposes is charged with organic matters in solution the best plan is to let it alone and go to a purer source.” The subsequent reports seem to give it up.

In fact the long struggle of the Department to keep up with the increasing demand, irrespective of quality, had now culminated in manifest inability. The City was short of water in 1877 and 1878, and in 1879 and 1880 the Chief Engineer did not hesitate to predict a water famine unless immediate measures were taken to increase the pumpage and distribution in summer.

In 1881 the suggestion is made that sewage should be excluded from the river to improve the quality of the water, and that the expense of preventing pollution would be far less than the cost of a remote supply.

A sample of water taken from the Corinthian Basin in the latter part of June was sent to Prof. Leeds of the Stevens Institute at Hoboken, who desired it for comparison with other waters. According to the Department reports the month of June was unusually wet and the sample was taken after two heavy rainfalls and one moderate one. The Schuylkill therefore took high rank with other waters collected about the same time, Brooklyn only surpassing it, but notwithstanding this, the chemical report states that while it is safe drinking water the albuminoid ammonia is twice that present in the Brooklyn water and approaches very closely to the maximum allowable amount.

The Report for 1882 states that from the determinations of Mr. Edwin F. Smith of the Schuylkill Navigation Company, an experienced observer, the minimum flow of the river in 1881 was under 170,000,000 gallons as compared with a previous determination in 1874 of 245,000,000 and in 1816 of 500,000,000, showing that the marked diminution in the minimum flow still continued.

The total decrease in sixty-five years (1816-1881) has therefore been 66 per cent., an average of over one per cent. per [PAGE 53] annum, and it remains to be seen how much further this will go. To appreciate the meaning of this decrease as illustrative of the changes that have taken place in the regimen of the stream and its great increase in variation of volume, producing corresponding variability in physical condition, it should be stated that the average flow throughout the year has been estimated at about 1,500,000,000 gallons daily with maxima several times greater. It is not probable that any considerable change has taken place in the total discharge of the stream so that whereas in 1816 the minimum flow was one-third of the average, in 1881 this proportion was reduced to about one-ninth, the sources of contamination meanwhile steadily increasing.

The 1882 report contains some discussion of pollution and urges its prevention, the subject being revived in consequence of an unhealthy condition of the upper Schuylkill due to deficient rainfall and the accumulation of refuse in the dams of the Navigation Company.

In October 1882, a Board of well-known engineers appointed by the Mayor, under the provisions of the ordinance of June 7, 1882, to consider what should be done for the present and future supply of the City, made a preliminary report. They find the Department plant to be dangerously limited and recommend more engines and boilers and additional storage. The Board calls attention to the necessity for complete surveys of localities whence a pure supply could be drawn, and are deeply impressed with the vital necessity of protecting the inlets to the stations from the large and constantly increasing amount of offensive sewage.

This brief resume of the history of the Schuylkill supply, derived exclusively from the official published reports of the Water Department, and without reference to the considerable body of current literature on the subject, consisting of newspaper and magazine articles, reports and discussions in medical journals, private publications and other sources, is given in order that some conception may be formed of the gradual [PAGE 54] deterioration of the stream and its increasing inability to fulfill the legitimate requirements of a water supply for the City, and as a suitable introduction to that systematic ascertainment of actual facts which was begun in 1883 and continued in 1884, upon which alone the City could base a correct judgment and formulate and provide the proper remedies.

In December 1882, and January 1883, owing to a low stage of the river covered with ice, and the drawing down of the upper dams and canal levels with their accumulation of refuse matters, the Schuylkill got itself into a state of extreme nauseousness so that a disagreeable odor was diffused throughout the house. Dr. Leeds was engaged to investigate this and his report is found in the annual report of the Department for 1883. He attributes the difficulty to the decomposition of organic substances contained in the water while the river was covered with ice, and therefore could absorb no oxygen from the air nor free itself of the products of decomposition. He found the river highly charged with organic matter and the albuminoid ammonia the highest at the Fairmount forebay.

He calls attention to the fact that in a stream like the Schuylkill, contaminated by sewers and factories, there is an incessant struggle between the constant pollution and the efforts of natural processes to restore the purity of the water. So long as these are not overtaxed the water may be used, but if surcharged with refuse, will deteriorate below the limit of admissible impurity, and this is often the case, especially at the Spring Garden and Fairmount forebays.

The Department report of 1883 contains a large body of facts and much discussion relating to the present and future supply. The Board of Experts made a final report in April, renewing their representations of the necessity for more power and larger reservoirs. Of the future supply they say: “At the points where the water for the City is now drawn its impurity is constantly increasing and is probably approaching the limit of wholesomeness. [PAGE 55]

“Formerly the character of the Schuylkill water was of the first rank among the sources of supply for cities. If this condition could be restored nothing better can be expected.

“The first duty of the City is to remove whatever sources of contamination are imparted within its own limits. The City’s ownership of so much of the banks of the river as are contained in Fairmount Park is of the greatest importance in this respect, but the efforts of the Park Commission to preserve the purity of the water have been rendered almost nugatory by the constantly increasing drainage into the river from the east bank, caused by the growth of large manufacturing industries, and their attendant populations.

“Your Board believe that analyses will show that the deterioration in the quality of the Schuylkill water, justly complained of, is largely due to this cause, and that the completion of the sewer from Flat Rock to below Fairmount will tend to restore its wholesomeness by removing a most serious source of pollution. The construction of this sewer has for many years been urged upon the city authorities; first, by the Park Commission, and subsequently by others who have considered the subject, and it is a matter for congratulation that the work is at last to be undertaken.

“Supposing, however, that when this sewer is in use, and when the City has exhausted all other means of preventing contamination within its boundaries, is it possible to control the pollution of the stream at higher points?”

Councils had at length authorized the surveys which had repeatedly been recommended, and the systematic collection of physical data was begun and supplemented by extended analyses and sanitary surveys.

Dr. Leeds observes that there is on the average a progressive rise in the ammonias contained in the Schuylkill from Phoenixville to Fairmount, and his preliminary conclusions are:

First. That the supply from the Delaware at Kensington should be abandoned.[PAGE 56]

Second. That natural agencies are ordinarily adequate to effect the oxidation of the organic matters in the lower Schuylkill and sometimes to raise its condition to one of great purity. At other seasons these agencies utterly fail through the intervention of unusual disturbing forces and the lower Schuylkill is non-potable.

“Inasmuch as these failures are periodic and inevitable the supply from the lower Schuylkill should be abandoned unless these agencies can be effectively supplemented by artificial means.”

The Chief Engineer remarks that “The Schuylkill, above Fairmount Dam, is the natural sewer, first and last, for a population of 350,000, largely engaged in manufacturing, and whatever may be the varying judgments of physicists as to the power of a running stream to purge itself of foreign contamination, it is very certain that the river itself has, from time to time, furnished the most convincing evidence of its inability to digest or dispose of the extraneous and injurious matters discharged into it.

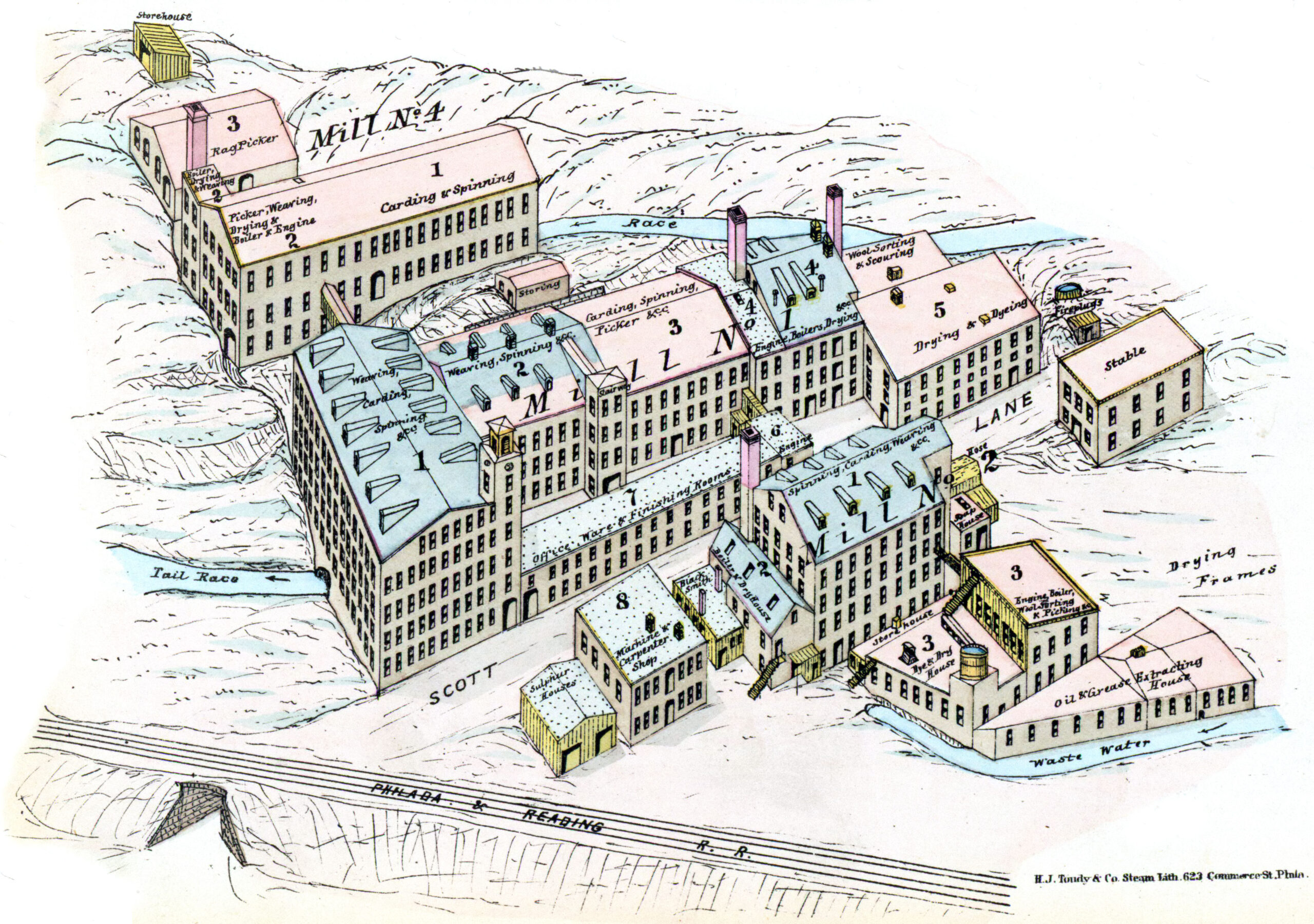

“The character of the pollution is as diversified as the occupations of the people. Sewage, chemicals, wool-washings, dye-stuffs, butcher and brewery refuse – there is almost nothing lacking – and the most singular feature of the case is that the worst and most deadly contaminations are those which enter the river within the city limits and under the control of the municipal authorities. The circumstance has this advantage, that matters can be amended whenever the City shall choose to exercise her powers, and the construction of the intercepting sewer on the east bank, from Manayunk to Fairmount, will no doubt be of great utility.

“It should not be believed, however, that the sewer – even should it accomplish all that it is designed for – will be able to do more than a part of the work. There will still be the entire pollution of the stream above the Flat Rock Dam to prevent or neutralize, the waters of the Manayunk Canal to purify, and the Wissahickon and other streams to regulate, and [PAGE 57] in addition there will remain sources of contamination within the limits of the Fairmount pool itself that are not the less deadly because they are concealed from view and escape direct observation.

“The movement of ground water is, in general, slowly towards the river, and it will be years before the sewage-saturated soil underlying along inhabited area, and filled with cess-pools, can free itself from poisons.

“In particular is there a subject from which sentiment and the imagination alike recoil, but to which the Engineer, in the interest of the public health, is forced to allude. Civilized communities have for generations recognized the danger to the living from the presence of the dead, and decreed that no well be dug in the vicinity of their last resting place, nor any water taken thence, lest the potency of lethal matter slay the living.

“Aside from the Engineering and other means of modifying the contaminations of the Schuylkill, involving years for their accomplishment, it must be said that little can be done to purify it. It is true that filtering the water will remove the visible impurities, and if thoroughly done, will render it a bright and sparkling fluid pleasing to the eye and generally acceptable to the palate, but the impurities thus removed are the least harmful of those contained in the water, and in reality, the river when muddiest from a recent freshet, is probably in its most wholesome condition, since it then contains the largest percentage of fresh water and the least of foreign matters. It is in summer, when the movement of the stream is the gentlest and the waters the most pellucid, that the largest proportion of dangerous contaminations is held in solution, and these the ordinary methods of filtering are powerless to remove. It is true that the passage of water through a mass of spongy iron has been found to oxidize in part the organic matter, but the cost of inaugurating a plant of this sort, or any filtering appliances such as are used in Europe, on the scale necessary to purify the water supply of Philadelphia, is too formidable to contemplate unless all other means of procuring a better supply shall prove impracticable. [PAGE 58] When all was done, the organic matters would still remain, and it is these which constitute the real danger. It is known that the germs of cholera, of typhoid fever and other diseases, although their real nature or function can only as yet be guessed at, may be carried by water which to every sense is pure, and that these germs may entirely escape detection by the most subtle analysis, while existing in a condition of the deadliest activity and only awaiting admission to a living organism to develop their latent morbific energy. Against this danger science has no absolute specific, although the boiling of water is supposed to destroy the germs.”

During the year 1884 the investigations and surveys relating to the present and future supplies were continued without cessation and in a thoroughly organized and systematic manner. The field work of these is nearly completed and the present year 1885 will be mainly devoted to the work of compilation and recording.

The sanitary survey of the Schuylkill valley was completed to include all sources of pollution above the dam at Fairmount.

The data were carefully collected by Mr. Barber whose appended report contains a full and concise account of the statistics of population and of the quality and amount so far as ascertainable, of the polluting elements which enter and are likely to enter the stream. A considerable amount of this could readily be intercepted or diverted with beneficial results, but there is a much larger quantity, such as the drainage of towns and the discharges from large mills, which could only be prevented from reaching the river by costly constructions.

As the facts were gathered they were submitted to Councils during the summer in successive reports covering Manayunk, the Wissahickon Valley and the remainder of the Fairmount Pool, and the variety and number of the sources of pollution within the city limits were shown to be so formidable that Councils who had already made provision for the partial construction of the many times recommended intercepting sewer on the East bank of the Schuylkill from above Manayunk to below Fairmount [PAGE 59] Dam, referred the reports to the City Solicitor with instructions to take such steps as were necessary to protect the health of the city from at least the more dangerous and readily remediable sources of danger. In consequence the Solicitor with great energy and good judgment, having made personal inspection of the several localities, selected three typical cases: one a house of entertainment with a large clientele and much water-closet drainage directly into the Pool near the mouth of the Wissahickon, another a particularly foul mill on the bank of the river in the upper part of Manayunk and a third another mill in Manayunk employing a large number of operatives whose excremental discharges passed into the stream. Against the proprietors of these, prosecutions were entered with the cooperation of the District Attorney, in the name of the Commonwealth, and after the finding of the true bills by the Grand Jury the cases were tried in the Court of Common Pleas No. 3.

Convictions were secured in all the cases and the judgment of the Court suspended to afford an opportunity for compliance with the requirements of the law.

The charge of Judge Thayer is so valuable a contribution to the law of sanitation and a declaration of the rights of individuals and communities in relation to the vital matter of the water supply as to justify its reproduction in this place.

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA 118. SOULAS et al. Pollution of river water used for drinking purposes. Charge by J. THAYER, November 25, 1884.

“Gentlemen of the Jury, the case which you are engaged in trying is one of much importance and your responsibility is proportioned of course to its importance. The facts which have been proved by the evidence given on behalf of the Commonwealth are very few and simple. They are however very weighty, and it is my duty to add, have not been contradicted. The law also upon this subject is very plain. The defendants are charged in this indictment with maintaining a common nuisance by causing the excrement and foul water from the water closets and urinals upon their [PAGE 60] premises, which are situated upon the bank of the Schuylkill river just above the confluence of the Wissahickon with that stream, to be drained into the river. It has been shown by witnesses, some of whom are experts in such matters, that the effect of this has been to pollute the drinking water of this city and to render it unwholesome and dangerous. Such pollution has also been shown by competent and credible evidence to have a direct tendency to produce disease in those who drink the water which is supplied to the city from the River Schuylkill.

“Now it is very old and well settled law that to pollute a public stream is to maintain a common nuisance. It is not only a public injury, but it is a crime, a crime for which those who perpetrate it are answerable in a tribunal of criminal jurisdiction. An Act of Assembly forbids and punishes as crimes all common or public nuisances, and I know of no public nuisance more serious in its evil effects and more obnoxious to the denunciation of the law than to corrupt and poison a public stream from which large numbers of people obtain their drinking water. If the jury therefore find that the defendants have done the acts charged against them in this indictment, no doubt whatever remains that they are guilty of the offence of maintaining a common nuisance and ought to be convicted. If the water drained from the defendants’ establishment into the river is of a foul and impure character, and if the effect of that is to pollute the water and render it unwholesome for drinking purposes, then they are guilty as they stand indicted, and it is your duty to say so.

“It is no defence to say that the premises are in the same condition and the drainage conducted in the same manner as when they obtained possession and began their occupancy. Their continuance of the nuisance is itself an offence against the law for which they are personally responsible. The law is perfectly well settled that no man can prescribe for a public nuisance, or defend himself by showing that others have violated the law before him. No length of time can justify a public nuisance, although it may furnish an answer to an action for a private injury. Public rights are not destroyed by private encroachments, no matter how long they have endured. Nor is it any defence that the river is also polluted from other sources, that impurities flow into it from sewers, and from towns and places above Manayunk.

“If the defendants have contributed to the pollution they are guilty. No man can excuse himself for violating the law upon the ground that others also violate it. It is said that the city ought to have built an intercepting sewer. But what of that? Perhaps it ought. But if the city has been guilty of negligence in that respect that fact does not justify the defendants in their violation of the law. It makes no difference whatever in the guilt of the defendants that the city has not taken steps to protect itself against the unlawful acts of those who pollute the stream. Nor ought your verdict to be affected in the slightest degree by the suggestion that if these pollutions of the river are stopped by indictments and convictions, the effect of that may be injurious to large business [PAGE 61] interests, which are prosecuted under similar conditions upon the river. You have nothing to do with that. Such considerations cannot affect your duty in the present case. The law is to be enforced, and those who violate it are to be punished, no matter what the effect of that may be upon their business, for the law is above every personal and private interest. All persons engaged in business are bound to conduct that business in subordination to the law, and in such manner as not to injure the public. It has been argued also that the city ought to have resorted to a civil remedy against the defendants for the correction of these abuses, that it ought to have gone into a civil court and asked for an injunction against their continuance.

“Such suggestions have nothing to do with the case. It is sufficient that the defendants are arraigned by the Commonwealth, to answer for an infraction of her laws. If they have broken those laws they are in the proper tribunal to answer for their acts. Civil proceedings are slow, and in such proceedings, where the parties are private persons or corporations, which are a kind of artificial persons created by the State, many embarrassing and dilatory questions might obstruct and hinder the speedy abatement of the nuisance. In my judgment the remedy which has been chosen is the speediest and the most effective. It is a proper and lawful remedy, and you have no concern now with any other.

“The defendants are before you to answer the charge of maintaining a common nuisance, which is a public offence by the laws of Pennsylvania. The simple question which you have to decide is, whether the defendants are guilty of this offence. If they have done the acts which are charged against them in this indictment, then, as matter of law, I instruct you that those acts constitute the offence of maintaining a common nuisance, and they are guilty. Upon the question of fact you have the testimony of numerous witnesses examined by the Commonwealth, and they have not been contradicted by any witnesses produced by the defendants.”

The jury found the defendants guilty without leaving the box. Sentence was suspended to afford the defendants an opportunity to abate the nuisance, the court intimating that if the nuisance should be immediately and wholly abated to the satisfaction of the officer to whom the supervision of such matters is entrusted by the city, it would be regarded as a sufficient satisfaction of the law, but unless this was done a severe sentence would be imposed upon the defendants, and the court, by virtue of the power conferred upon it by the Act of 1860, would, in addition, order the sheriff to abate the nuisance at the expense of the defendants.

The great importance of this adjudication as an exposition of the law of the land and indicating an effective and speedy method of righting abuses even of a long standing can hardly be overestimated, and must be attended with the greatest benefits wherever its authority and application shall be found to be necessary. [PAGE 62]

In particular will it no doubt effect a large decrease in the more dangerous contaminations which in great quantity reach the Fairmount Pool whence the main supply of Philadelphia is drawn, and to this end Councils and the several Departments of Law, Health, and Water have addressed themselves and will no doubt continue so to do.

Dr. Leeds’ report will command close interest and attention. The systematic prosecution of his inquiries during nearly a full year not by occasional laboratory investigations, but by frequent and regular analyses in connection with personal local examinations enabled him to reach certain well defined conclusions in regard to the actual and relative condition of the several streams under consideration, which are of very great value in connection both with the present and future supplies.

He notes the great variability of the Schuylkill and its gross pollution by sewage. At some seasons the natural remedial agencies are adequate to the elimination of contaminations and render the waters potable and pleasant. At others they are quite unequal to the task and popular disgust and indignation are aroused.

The means of amendment are manifest–the exclusion of sewage, the modification of mill waste and the final purification and clarification of the water before delivery to the consumer.

In conclusion he says: “Whatever may be done in the future it is certain that one thing should be done at present and at once, and that is the rigorous exclusion of sewage from the Schuylkill, for on this point the most eminent authorities agree that the presence of sewage in drinking water is a predisposing influence towards cholera in time of epidemic, and an important factor at all times in the dissemination of intestinal disorders in general.”

The history of the Schuylkill is both interesting and instructive. In earlier days a noble river with a bountiful and healthful drainage area of woodland, mountain, and meadow, pouring a powerful and fairly equable current of pure water through its channel, the occupancy of its valley and the [PAGE 63] growth and development of population and industries from source to mouth have greatly modified its characteristics.

Generation after generation made fresh inroads upon its resources and added its quota of varied pollution, until at length the river, whose pure volume for a long period was able to eliminate the evidence of man’s careless work and presence, and which even yet might have continued to do so were it not, Samson-like, shorn of its power of conservation by the ruthless cutting away of the forests and clearing of the land upon which it depended to equalize its flow, has become a sewage and trade-polluted stream whose failing volume in seasons of drought is unequal to the nauseous task of digesting and disposing of the extraneous and dangerous matters with which it is surcharged.

For the greater part of the year though subject to great variations in volume and quality from freshets due to the rapid accumulation of rainfall it is still a fairly good water and at times notably so. Again, as its power wanes, the constant accession of deleterious matters overloads it with contaminations, and its waters become foul and unwholesome.

The dwellers on the Schuylkill are not alone in thus failing to take the precautions which finally must be forced upon them. The world over, ignorance, carelessness and an apathy born of long immunity from retribution, have fouled the water courses whence the supply is drawn and only when an epidemic sweeps away its victims or a special and unusual fit of unwholesomeness seizes the stream is attention called to the necessity of amendment.

It is probable that mankind as a rule must continue to rely upon water courses for the needful supply. Very pure water may in some cases be derived from deep wells, but as a rule the quantity is limited and uncertain, and furthermore, water removed from contact with the air if at all polluted is liable to assume a dangerous capacity for infection from the absence of a surplus of oxidizing agencies. We must no doubt look to the mountains, whose sloping sides and inhospitable soil forbid [PAGE 64] occupancy, as the gathering ground of water for the supply of the communities existing between them and the sea, and one of two things must be done: either the streams flowing thence must be protected as thoroughly as practicable throughout their length, or their sources must be intercepted above any polluting causes and conveyed by artificial channels to the point of delivery.

A good drinking water should be transparent, cool and sparkling, without color, odor or taste, with but a small amount of innocuous mineral matters in solution, the least possible quantity of vegetable matter, and be absolutely free from animal matter and in particular from excremental pollution.

It is no doubt true that water contaminated with organic matters even of the vilest descriptions (and in this respect as in some others man is his own worst enemy) can be drunk for long periods without noticeable or traceable effect upon the system. Nevertheless, in such matters the instinctive animal sense is a safer and more intelligent guide than he who would assert the innocuousness of such admixture.

If the pollution were done before our eyes no one would think of using the water, but occurring out of sight we close the mental vision as well and literally go it blind.

There is now little if any dispute among instructed and scientific men that infected water is a common carrier of disease and that the continuous propagation of intestinal epidemics in especial is effected by this means, chief among them being typhoid fever and the choleraic diseases.

One of the very highest authorities on this subject, Dr. Sternberg, of the United States Army, in a recent article says: “There is little doubt that the intestinal fluxes generally, from the dread Asiatic pestilence to camp diarrhoea, are produced in this way by micro-organisms which for the most part find their way to the interior of the body in drinking water.”

It has been contended however that a flowing stream possesses the power of self-purification and it has therefore been [PAGE 65]assumed that matters deleterious to health may thereby be eliminated. There is much basis for this belief, but it would be dangerous to carry too far.

A flowing stream exposed to the full action of the atmosphere and the solar rays, especially if in rapid and turbulent motion, will undoubtedly effect the disappearance of matter which offends the senses, and of invisible organic substances in solution.

The organic and putrescent matters are oxidized and converted into innocuous residua which may be deposited upon the bed and banks of the stream. This is true of dead matter but how shall it be shown to be true of those living microscopic plants which scientific investigation has revealed to us as the agents of deadly disease as well as of indispensable natural processes of purification by the disintegration of effete matter.

The weight of evidence is heavily against this theory. It has been proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that water which to every sense is pure may be charged with the most active and deadly potency from the presence, undetectable by any analysis however subtle save the methods of modern microbiology, of those beings whose power for good or ill seem to be in inverse proportion to their physical dimensions.

Furthermore, since the natural operation of purification depends upon the chemical action of oxygen, how shall it be perfected, supposing that the water has exhausted its supply of that powerful element by a previous charge of pollution, and therefore no longer has the weapon with which to contend with a new enemy?

It follows therefore that since disease may lurk in the most pellucid and attractive water, security can only be attained by such precautions as shall positively insure its protection from the germs of disease; and to do this all dangerous matters must be kept out.

An admixture of what may be called “healthy sewage,” however it may disgust the sensibilities, can no doubt be absorbed without certain injury, but we can never be sure of the [PAGE 66] physical condition of the persons whence that sewage is derived, and knowing what we do of the fatal character of certain diseases and of the mode of their propagation and transmission, what safe or decent course is there other than the rigid exclusion from our water supply of all those foul waste matters which the instinctive impulse of every animal rejects, and which over and over has been proven to convey the seeds of death – whose vitality is extremely persistent, and whose presence or absence could only be determined by actual tests upon living beings?

While trade and sewage contamination may be in great part kept from the river by an extended system of sewers or complete local epuration before being allowed to enter the stream, the frequent turbidity of the Schuylkill is an ineradicable defect. It is due to the heavy rush of the rainfall down the slopes of the river and its affluents, from which at times the water is highly charged with sediment.

This sediment may be composed largely of insoluble earthy matters, and to that extent be innocuous to health, but it always destroys the appearance and potability of the water, clogs the pipes, and causes even greater public dissatisfaction than the more serious but unseen evil.

The only remedy is the establishment of filtering appliances, on a scale sufficient to clarify the entire supply of the city, and these may take the form of filtering basins or of filtering plant and apparatus. These for so large a quantity as the city even now requires will cost a large sum, and for the present and until adequate storage and distribution facilities shall have been provided their introduction must be deferred.

The experiment of artificial aeration of the water to supply the lacking oxygen and decompose in part the organic substances present in the water, is about to be tried.

The investigation of this subject last spring and summer by Dr. Leeds made it probable that useful results could be attained at a very moderate cost. His laboratory experiments tended to show that the well known beneficial action of aeration upon [PAGE 67] water would be greatly increased by effecting the commingling of the air and water under pressure, whereby a much more rapid and considerable absorption of oxygen by the water could be secured.

To effect this the simple and economical expedient of forcing air into the mains at the pumping stations where the pressure was that due to the elevation of the basin above the pump, and where the requisite power was at hand, suggested itself.

As no means were available for the purchase of air compressors, one-half of one of the two pumps operated by a turbine at the Fairmount Station, was converted into an air pump whereby the desired percentage of air, viz: about 20 per cent. by volume at the atmospheric pressure, was injected into the mains. The water thence passed through 3,000 feet of main to the Corinthian basin about 120 feet above the pump and therefore, under an initial pressure of about 52 pounds. Under these circumstances the effect of the aeration was quite marked. The chemical data of comparison are given in Dr. Leeds’ report, from which it will be seen that the carbonic acid was very largely increased and that the oxygen, notwithstanding its activity en route was at the end about 20 per cent. more than at the beginning. These results were so encouraging and so fully corroborated by a similar experiment on a larger scale made with the Hoboken supply at the suggestion of Dr. Leeds, that Councils made appropriation for partly equipping the Department with proper air compressing apparatus at the stations and these will shortly be in operation at Belmont and Spring Garden. While the Schuylkill supply is continued it is expected that the quality of the water can be much improved by the use of the process although it should be said that aeration can have but little effect on turbidity merely and will not therefore appreciably improve the appearance of the water.