I am presenting this page more or less as I wrote it for PhillyH2O in 2005. Now, almost 20 years later, many more resources are available to anyone doing this type of neighborhood research, and I could add a plethora of photographs and new information from newspaper databases and books that have been published since. But I think the information presented here is still valid, and the images – if smaller than others that I have been using on new pages on this site – still do the job of explaining some of the changes in this neighborhood as it grew. Someday I may revisit this page and give it a modern makeover, but for now I will let it stand as a remnant of my early web efforts.

One good piece of news about Overbrook Farms is that the Philadelphia Historical Commission created an Overbrook Farms Historic District in 2019, which offers some protections for the architecture and the character of the neighborhood. You can download and examine the 1209-page (that is not a typo) nomination form, which includes a complete history of the neighborhood along with photographs and details for many individual buildings. In 2014 an excellent picture book, Overbrook Farms, was also published as part of the Images of America series from Arcadia Publishing. –Adam Levine, PWD Historical Consultant, 2024.

By Adam Levine

Under contract with JASTECH Development Services

(Copyright 2005 and 2024)

A Note on Sources

An invaluable source for this research was the 1936 book, Overbrook Farms, by Tello J. d’Apery. Much information was also gleaned from examinations of old maps, and from the annual reports of the Surveys Bureau of the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Works.

Introduction

How an urban neighborhood develops, and at what pace, depends on a number of interrelated factors. Among the many factors that affected the development of the Overbrook section of West Philadelphia was the taming of the area’s natural topography by an overlay of urban infrastructure. This act of engineering hubris by 19th-century urban planners, coinciding as it did with large tracts of available farmland and easy rail transportation into the city, made the area attractive to real estate developers looking to create a suburb of upscale homes.

The following report focuses mostly on Overbook Farms, the first section of Overbrook to be converted from farmland to residential housing. This area is particularly interesting from the environmental standpoint, because of the documentation available detailing changes made in the original topography of the neighborhood during the course of its development. Under the limited scope of the present contract, I thought it best to begin here, but this report should be considered just a preliminary survey of the changes in Overbrook over time. Similar topographical information could be uncovered for the sections of the neighborhood that developed later; and the entire story might, in time, be brought up to the present with a discussion of the social changes that have changed the racial face of Overbrook since 1950.

Overbrook History: The Creeks

In the many millennia before European settlers arrived, Overbrook and the surrounding area had been considered a well-watered wooded area, reputed to be good hunting grounds for the local Native Americans. When the first whites began to make their way inland from the Delaware River in the 17th century, they were attracted to the locality by these same features. The land, once cleared of trees, proved to be fertile farmland. The small streams, once dammed, provided power for numerous mills. Grist mills ground grains into flour and meal. Saw mills took the trees clread from the land and turned them into lumber, for local buildings and those in the nearby city. Paper mills and gunpowder mills were also in operation along the local creeks for a time. In the 19th century, with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, textile factories were built that employed hundreds of men, women, boys and girls. Even after these factories converted to steam power by the mid-19th century, they still used the creeks as sources of water for their bleaching and dyeing operations, and as receptacles for their wastes.

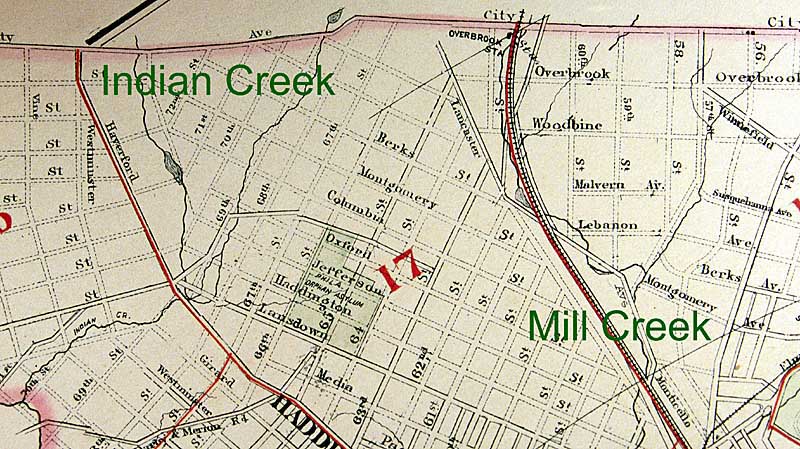

Mill Creek

Mill Creek, which once ran through the heart of present Overbrook, was buried underground and incorporated into Philadelphia’s sewer system in the last decades of the 19th century. It was a small creek, especially in its upper reaches around Overbook. The section north of City Avenue, in Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, still runs above ground, and in times of normal flow an energetic child could easily jump across the narrow stream. Once it entered the city, the main branch of the creek roughly followed the railroad until about 55th street, where it turned farther southeast, finally emptying into the Schuylkill River along the line of 43rd Street.

Like all natural stream systems, Mill Creek had many tributaries, the largest being George’s Run, named for the George family, which owned large farms in Overbook and other sections of West Philadelphia. Smaller tributaries closer to Overbrook – such as one that entered the city near 59th and City Line and ran roughly on a diagonal before joining the main branch of the creek around 62nd and Lancaster – sometimes show up on old maps. But a number of 19th century mapmakers, as the examples in the accompanying materials show, often simply ignored the creeks. Instead of showing the city as it actually was at the time, they were eager to show the world what the city would eventually become.

Even on those maps that do show the creeks, the grid of proposed streets is often laid right over them – and in most cases, this plan for the city became reality. Like Mill Creek, a majority of the smaller creeks in the older parts of the city were either put underground in sewer pipes or otherwise rerouted or diverted or dried up – in one way or another, obliterated from the city map. Once the creeks were buried in pipes, their valleys were filled in (often with material cut down from surrounding hills) as the terrain was made more level, to accommodate the city streets and underlying infrastructure.

In traveling around the present-day city, a discerning eye may detect the low points in the city streets. These remnant valleys often indicate the routes of one of the city’s many underground streams. But most eyes are not so discerning; in most cases, the creeks that flow in pipes beneath the city (many of them carrying sewage along with their original freshwater flow) are forsaken and forgotten. It was not surprising that when a section of the Mill Creek sewer near 51st and Brown collapsed in 1961, swallowing up four houses and taking three lives, it was the first time many people in the Mill Creek area of West Philadelphia learned the origin of their neighborhood’s name.

Benjamin Boggs, an area resident who was fascinated with Mill Creek, wrote about the creek in 1912:

“Standing upon City Line bridge over the railroad one may see…the headwaters of Mill creek, a tiny stream sparkling in the sun shine beneath the line of old willows which border it for hundreds of feet. The creek is only a baby here, scarcely three feet wide, and runs in [a] carefully stoned bed. It disappears into a tunnel under the railroad tracks at Overbrook station (thanks be to the poetically inclined person who perpetuated its memory in the name of the depot) and then, for all the long miles to the Schuylkill at Woodlands, it burrows foul and unpleasing beneath the surface.”

Indian Creek

Indian Creek, a tributary of Cobbs Creek with two branches crossing City Avenue at 66th and 72nd Streets, did not suffer the same fate as most Philadelphia creeks. Instead of being buried in a sewer pipe, as early maps of the area suggested would happen, both the east and west branches of the creek are preserved mostly intact in Morris Park, thanks to a gift of land around the creek from Wistar Morris and other adjoining landowners. This initial gift of land, which follows the course of the branches from City Avenue to their confluence around 68th and Haverford, was eventually continued further downstream to connect with the newly formed Cobbs Creek Park around 1910.

Only a short part of the West Branch, and the confluence of the two branches, is now buried underground, carried in a large culvert beneath part of Morris Park and Lansdowne and Haverford Avenues. The Philadelphia Water Department’s Office of Watersheds is currently (Summer 2002) undertaking a survey of Indian Creek, which should provide a great deal of information for anyone with an interest in the health of the stream and the surrounding parkland. [UPDATE in 2024: In 2012 the buried section of the West Branch was daylighted in a new channel that goes around the ballfield and connects with the East Branch above-ground. See this story map for more information about Morris Park and Indian Creek.]

Mill ponds and mill races

Maps of both Indian Creek and Mill Creek from the 19th and early 20th centuries show a series of mill ponds (formed by dams in the creeks) and mill races (man-made channels dug alongside the natural creek beds, which carried water from the mill ponds to the mills) – features that never seem quite the same from map to map. Some of these changes may be attributable to the inaccuracies of the mapmakers, but might also be due to the waxing and waning fortunes of the mills themselves, which would either increase or lessen the need for the water the ponds and races supplied.

Another factor may be that, like any infrastructure, the ponds and races needed regular maintenance. Without this work, dams may have broken and the ponds behind them drained out; or the races couild have been filled with silt, or their banks may have caved in. Since both creeks were relatively small, with little “power” to offer in their normally low flow of water, some of the changes may also reflect attempts at re-engineering the system to provide more water to the mill at a greater height (the greater the “fall” of water at the mill, the higher the amount of power that could be derived from it). Whatever the reasons, the variations in the maps might reflect the never-constant situation of both the natural creek systems and the businesses that altered them to suit their ever-changing needs.

Overbrook History: From Farmland to Residential Development

These scattered manufacturing interests notwithstanding, much of West Philadelphia west of 40th Street retained its rural farming character well into the 19th century – even into the 20th century in the areas farthest removed from easy access into the city, transportation being one of the factors influencing the “how and when” of an area’s development. The Pennsylvania Railroad, with its stop at Overbrook (named for the small stream, Mill Creek, that was carried under the station in a culvert), provided one way to get into the city, but before its construction in the late 1830s, the main route of travel was the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike (now Lancaster Avenue).

Opened in 1795 as the country’s first toll road, it was the first important public improvement in the state. Nine tollgates were set up along the 62-mile road, including one at the City line and another near where 56th Street now crosses the road. Eventually 67 taverns set up shop along the roadside as well, providing abundant refreshment opportunities for passing drovers, carters and travelers.

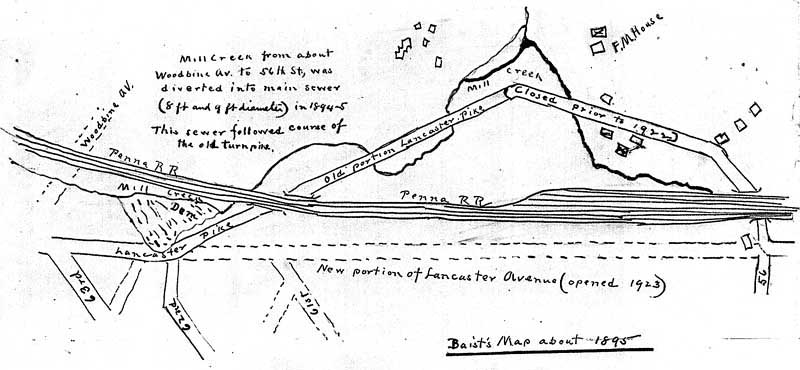

Lancaster Pike remained a toll road until 1917, when it was purchased by the state. Except for a meandering section between 56th and 62nd Street, this road more or less followed the route of the present-day Lancaster Avenue. Construction of the new, straightened section west of 56th Street involved cutting through a steep hill, and was completed in 1922. Most of the old section of roadway is now covered by SEPTA’s rail maintenance yard.

In 1912, local resident Benjamin Boggs took a walk along this old section of Lancaster Pike, in search of remaining evidence of the route of Mill Creek, which he reported as follows:

“West of 63rd Street Lancaster Pike is a fine Boulevard for many blocks; east of 56th Street it is a poor squalid city thoroughfare. Between the two, and the distance is greater than would appear for the old road winds and twists, it is the ancient highway of our grandfathers unimproved and unspoiled–just a good old country road. Less than a thousand feet east of 63rd Street all houses have disappeared. One walks over an ancient road in the haunts of ancient peace, the passing trains alone disturbing the quiet. Is that the jingle of an old-time Conestoga? Oddly enough the bells draw nearer, and one almost expects to see a Lancaster county farmer come around the bend, but it proves to be a dump coal wagon with bells on the horses, an unusual thing nowadays. There are quarries on the south side of the road east of 62nd Street. On the upper or north side between the road and the railroad, leading down to a narrow point where the latter crosses the pike overhead, is an enclosed marshy meadow which I recollect very well indeed as a mill pond in the early [18]80s. It was a goodly size dam with water flowing over its breast, this being the Mill Creek. What mill it supplied I never knew, but now all is changed, and the old dam is buried deep, stone breast and all, beneath the filling which has converted a water course into a building site. (The property belonged to John and Joseph George in 1875.)

“Following the pike beneath the railroad arch, the bed of the Mill Creek is yet visible skirting the hillside, albeit much filled in with rubbish and dirt. The abutments of some old-time lane bridge can yet be seen close to the arch on the upper side. For a thousand feet or more, the pike is upon a causeway across the swamps (yet moist although little water is apparent) and a milestone announces that is it “4M to P”. Old buttonwoods edge the road.

“At the next bend another valley comes in with traces of a branch of the creek. Ugly sewer manholes reveal where the unfortunate stream now is hidden, and these we will find constantly ahead of us. The new valley is being buried twenty feet deep or more with city refuse. The first house we have thus far met is at the bend, on the railroad side. It is small and of stone. Right here the creek evidently crossed under the pike and the garden of the house seems to be in its old bed. Here too a sewer stands eight or ten feet higher than the pike, showing how all this will be buried sooner or later. Down a path through the weeds is a spring, clear, cold and sparkling. A group of Negro ash cart drivers stop and go down for a drink, as doubtless scores of other carters have done this hundred years and more. There is a stone cottage on the upper side of the road, originally but one story high, to which have been added two more stories of frame, making an odd structure. Back of it is a little one stor[y] stone cot[tage] pleasing and clean. It is occupied. Further down on the railroad side is a two story stone dwelling falling to decay.

“A good farm house and outbuildings, all of stone which in 1875 belonged to Wm. E. Longstreth, stand at the next bend, high above the pike. We are close to the recrossing of the road beneath the railroad, and a line of five old trees on the south side of the pike just at the railroad embankment show where the old creek ran. The pike crosses under the railroad through a lone tunnel and when we reach the other side we find the tunnel to be on the line of 56th street. The pike turns easterly, and we go with it no further. The creek was west of 55th street here, and the buildings of the Overbook Carpet Company are erected partly over the old bed. A little further down 56th street, however, the ground gets quite high. Streets are now being cut through the hill are thirty feet or more from the original surface; huge work for builders.”

By the end of the Civil War, by which time Center City was mostly built up from river to river, pressure was growing to develop the farmlands west of the Schuylkill River. The deep valley of Mill Creek, meandering for five miles from 43rd Street on the southeast to 63rd and Overbook in the northwest, posed a physical barrier to the city’s westward expansion, and not until the creek was buried in a sewer was the city’s westward expansion able to proceed.

The conversion of Mill Creek into a sewer began in the downstream sections in 1869, slowly progressing upstream as the city’s Select and Common Councils allocated further funds. The pace of the work picked up in the 1890s, and the sewer finally reached Overbrook around 1892. It is no coincidence that the next year marked the start of work on Overbook Farms. A project of Drexel and Co., a major investor in the Pennsylvania Railroad, this grand housing development was built on a 168-acre farm purchased for $425,000 from the estate of John M. George. The investors in the project hoped it would pay back in two ways: by the profits to be made in reselling the houses and lots, and by increasing the ridership on the railroad, which ran scores of trains a day that stopped at Overbrook Station.

The property was about evenly bisected by the railroad. Much of the section north of the tracks sat in the uneven valleys of upper Mill Creek and its tributaries, property that would have been undevelopable as planned without putting these streams underground. City engineers justified the expense of this and many other sewer projects by citing statistics showing how the cost of these improvements was repaid to the city coffers, in just a few short years, by the tax revenues from buildings put up on adjacent land. This quick payback would certainly have been the case in Overbrook Farms, where over four hundred homes were eventually built, costing between $7,000 to $18,000 per house and lot.

It should also be noted that, while the city paid the expense for building the sewers to carry these streams, and for filling the streets above the pipes to the proper grade, it was up to the property owners to make their lots conform to the level of the streets by either filling the low ground or cutting down high ground as needed. Work on the Mill Creek sewer was mostly completed by 1895, but in areas of outside the immediate Overbrook Farms development, it might take decades to completely fill in the some parts of the old valley, depending on either the state of the real estate market at the time, or a particular landowner’s urgency in developing the property.

Overbrook Farms

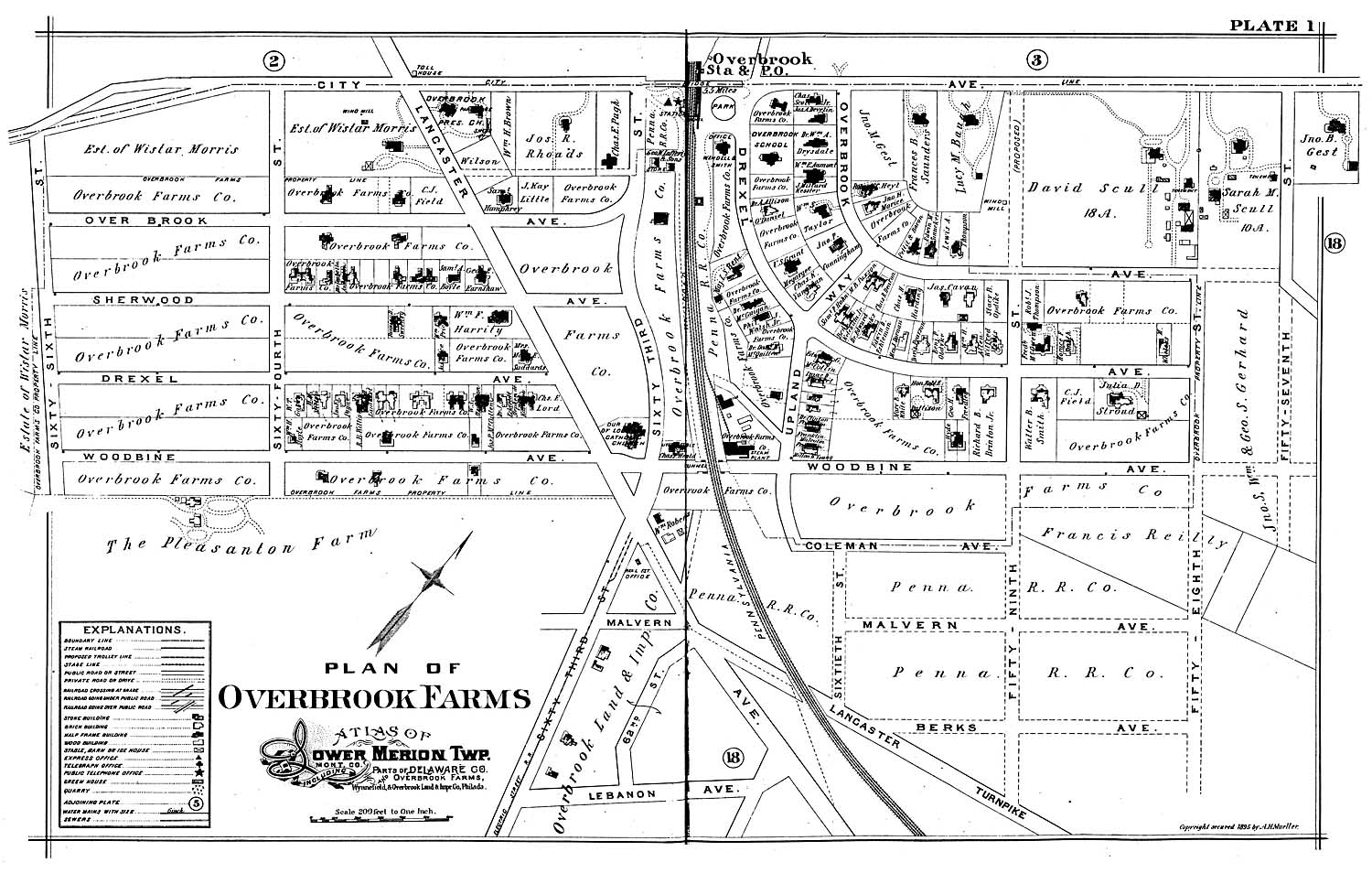

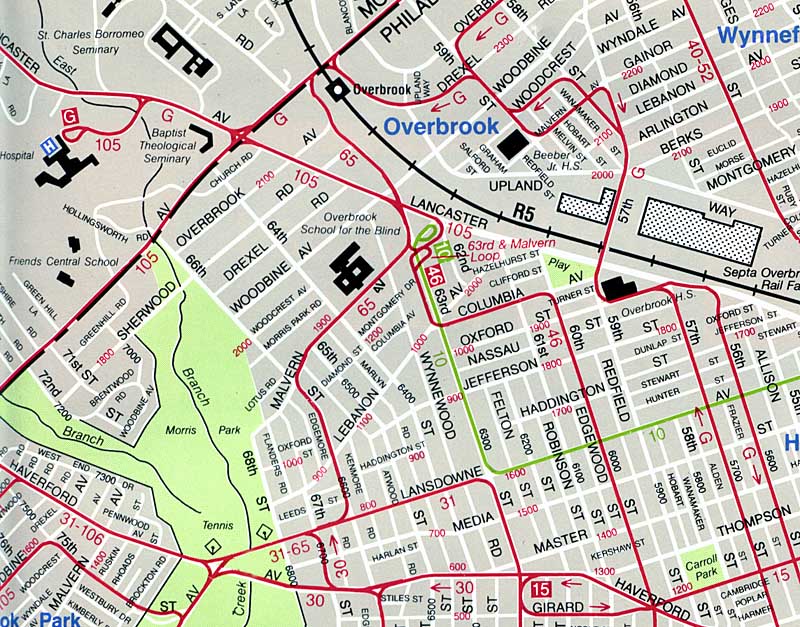

The map at the top of this page shows the extent of the original development, bounded by 58th Street on the North, 66th Street on the south, City Line Avenue on the west and Woodbine Avenue on the east. The firm of Wendell & Smith was in charge of the project, and the first building they erected was a stone office near the railroad station. Construction began in early spring 1893. From 300 to 400 men worked on the project during the first two years. Finished houses were heated with steam provided from the development’s own steam plant, electricity from its own generating station, and water from its own wells.

According to a promotional brochure, “Overbrook Farms: The Suburb de Luxe,” 77 trains a day stopped at the Overbrook Station, making the six-mile trip to Broad Street Station in 12 minutes. As the investors had hoped, many of the heads of household rode the trains every weekday to their work in the city. The brochure also noted:

“In addition to the city comforts Overbrook Farms offers many advantages exclusively its own. Because of its country surroundings and lofty, open situation – from 200 to 250 feet above the level of the city – the air is naturally much purer and infinitely more healthful than that of the congested city. Coolness in summer and good drainage are other benefits of this high location. Proximity to a rich farming district enables Overbrook residents to enjoy daily deliveries of fresh country produce, or, at the same time, to market in Philadelphia quite as easily as their neighbors in the city….”

“Philadelphians who have despaired of rendering Schuylkill water fit to drink, even by boiling and filtering, will be interested in the fact that Overbook water is pure and clean at all times. It is piped to every resident from our own artesian wells. The connection between impure water and disease is too well known to require comment. During the typhoid epidemic in 1898, when many deaths occurred in Philadelphia, there was not one case of this dread disease in Overbrook Farms, though right on the border of the city. The water supply is obtained from wells bored to a great depth through clean sand and gravel to solid rock. Clear, cold, sparkling, shown by analysis to be perfectly clean, this water is perhaps the greatest luxury Overbrook offers.”

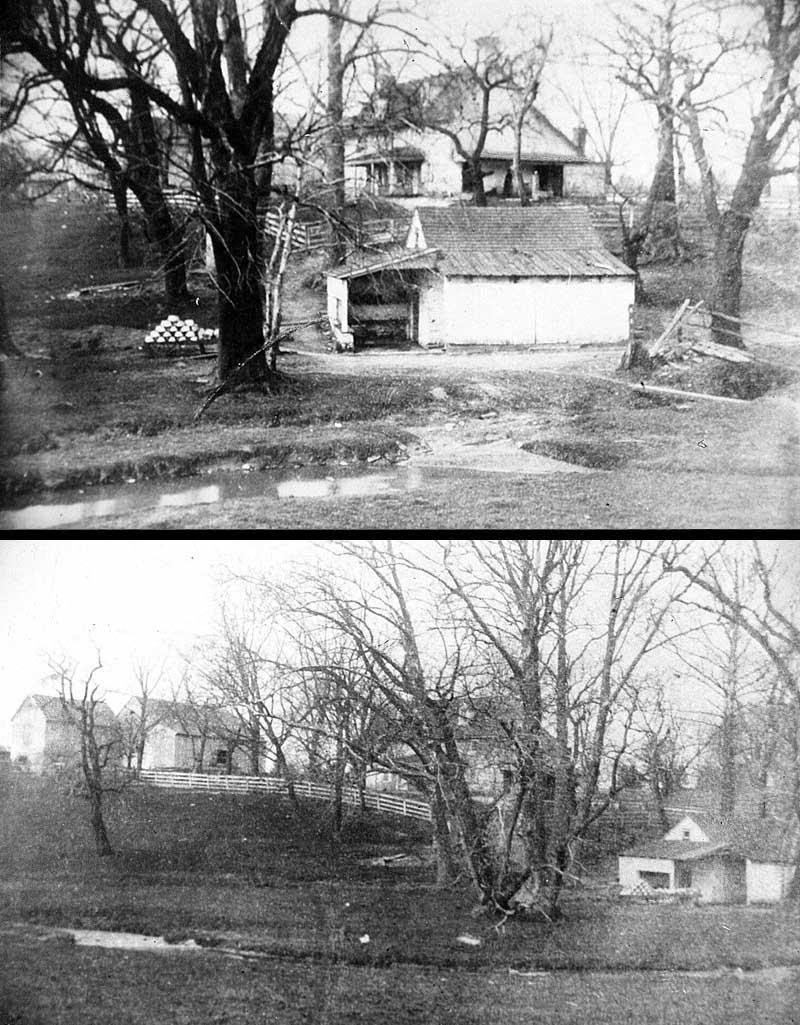

In the 1936 book, Overbrook Farms, local resident and amateur historian Tello J. d’Apery gives a fascinating account of the construction of this development, especially vivid in its details of the changes in topography wrought by the builders. Trees in several heavily wooded areas – near Woodbine between 64th and 66th; on Upland Way from Overbrook to Woodbine; and from Drexel Road to Woodbine Avenue near 58th Street – needed to be thinned out to make room for the houses. Some stately old specimens were left standing, and new saplings were planted as soon as the streets were completed

“Little streams ran through the farmland, which had to be drained and filled in,” d’Apery wrote. “There was a [tributary of Mill Creek] running down Upland Way and the ground east of Upland Way was so swampy that it was under-drained with tile and French drains. From the grounds of what is now the Episcopal Academy this creek crossed City Line at 59th Street, ponds being formed on [adjacent] properties for the purpose of procuring private ice supplies. Mill Creek started above Merion Station and, running south, continued under the Overbrook Station, and followed the general line of the present 63rd Street. Another small stream ran on Sherwood Road down to 66th Street.”

Cutting and filling went on throughout the development. Upland Way, to within 100 feet of Woodbine Avenue, was filled in from 4 to 6 feet. Near Overbrook Avenue, 64th Street was filled in over 10 feet. A small ravine at Sherwood Road and 66th Street – which must have been the location of the above-mentioned “small stream” – was filled 12 feet. Several cuts needed to be made in high, rocky places, and quarries were opened at those spots, with the stone used both in the houses and on the roads. At Drexel Road west of 59th Street, stone was removed from an 8 to 10 foot cut, while a stone ridge along Woodbine from Upland to 58th was cut down as much as 12 feet. A larger quarry was opened at Woodbine and 63rd, which was from 25 to 30 feet deep, and on which no building was erected for many years afterwards. There was also another large quarry in the vicinity, on the southeast corner of 62nd and Lancaster. All told, more than 75 per cent of the stone used in Overbook Farms came from the property itself.

D’Apery also includes a chronology of street openings, which would be confusing in print but could make a very interesting series of map overlays, showing the quick growth of the area from year to year. In a final note, he wrote that most people wanted to build on the side of the development north of the railroad tracks. “It was difficult to persuade them to live on the other side, because they said it was such a ‘wilderness’ they would have to put ‘bars at the windows.'”

A 1932 article from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin summarized some of the changes in West Philadelphia in the preceding forty years:

“In the middle of the [18]90s…Overbrook, under the quickening enterprise of Wendell and Smith, was a community of new homes, a distinct development…separate and apart from the rest of the city. Old Philadelphians went out to look at ‘the new section’ as explorers….While there were marks of [West Philadelphia’s] new development already apparent at the start of the century, a traveler west of the Schuylkill at that date still saw acres of corn growing …around 46th and Spruce Streets, plenty of old shade trees and fine lawns along Walnut and Chestnut streets. There was an ash dump where Clark Park is now and a brickyard where Carroll Park is, and here and there old lanes cutting diagonally across the outer wards…. Growth of West Philadelphia did not come all at once…. It took time before Overbrook came down to join hands with Haddington, before Paschallville and Elmwood were linked, before the Aronomink and Sherwood sections became indistinguishable in their obliteration of old bounds, or Angora lost its identity.”

The creation of Overbrook Farms was just the beginning of a process of development that, in other neighborhoods of West Philadelphia, would continue for decades.