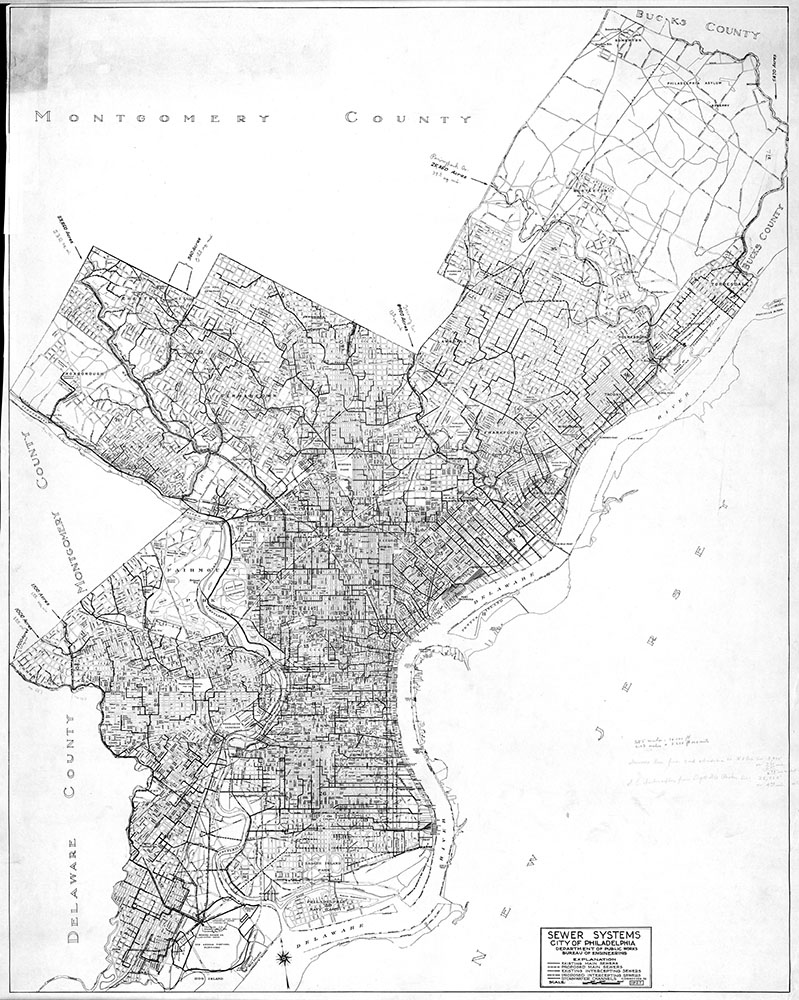

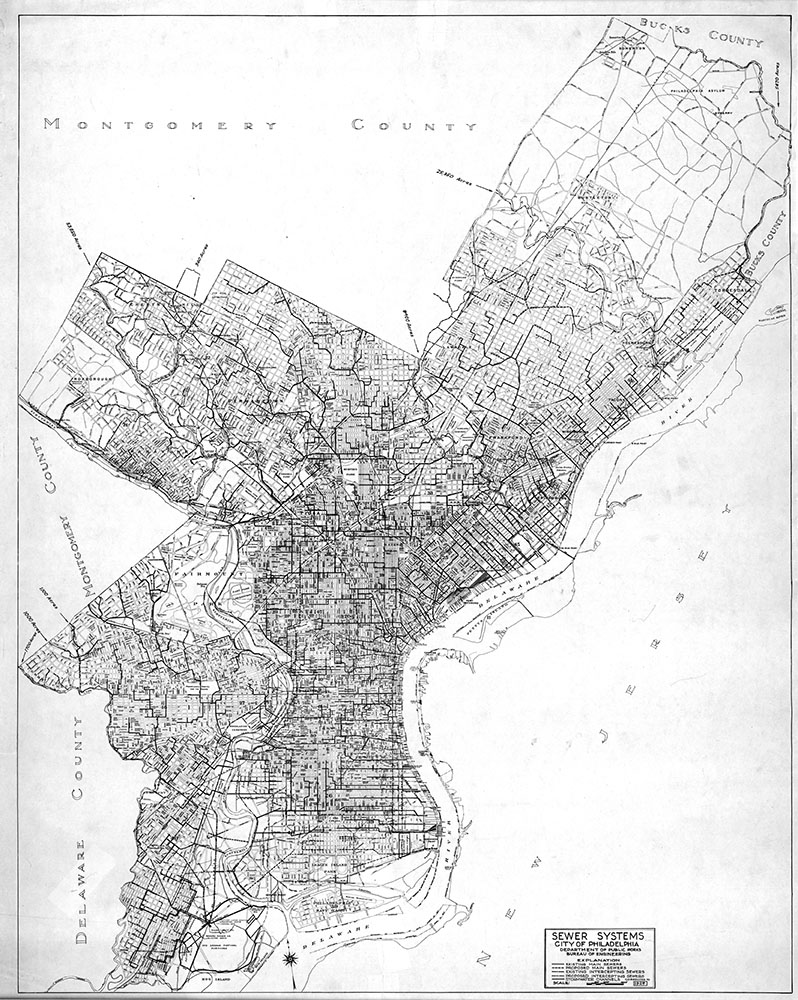

These two maps, created by the city’s Department of Public Works, show the extent of the sewer system on the eve of the Great Depression. The original ~750 mb digital files for both were reduced in size and quality for presentation here, but the main details are still readable. If anyone wants a clearer image of a particular neighborhood, let me know and I can provide that.

Someone with an eagle eye could probably find slight differences between the two, and I’d be curious to know if anyone bothers to do that. But to my mind the maps show the same things – the extent of development in the city at that time (which tended to follow the construction of sewers), and the areas of the city in which sewer extensions were lagging behind development.

The latter included Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood such as Oak Lane, Fern Rock, Lawndale, Rhawnhurst, and Burholme, where backyard cesspools were a throwback to the 19th century, when each property in the city dealt with its own wastes in what were called privy pits. The expansion of the flush toilet and the combined sewer system made the city’s countless privies obsolete in most neighborhoods, but for various reasons sewers failed to reach all who needed them. Through the first half of the 20th century, newspaper stories repeatedly reported on promises (often not kept) to provide this basic city service.

Sewage, after all, is simply the back end of the city’s water cycle, in which raw water from rivers is made safe to consume and piped to users in homes and business, who then flush the used water (or sewage) into the city’s sewers, where it is collected and treated and made safe to return to the rivers.

This is, of course, a gross simplification of the work of the Philadelphia Water Department. But what seems obvious to us now was not so clear a hundred years ago. Complicating factors, back when these maps were made, were the limited tax revenues during the Depression, and the diversion of material such as steel and concrete into the subsequent war effort – money, steel, and concrete all being necessary for the construction of sewers. [You can learn more about these problems in this editorial, from the March 1941 issue of The Nor’Easter, a publication of the Northeast Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.)

Eventually sewers caught up with development, in Burholme and other underserved neighborhoods, but other problems have since come to the fore, as they always do. Running a big city is like playing a game of Whack-A-Mole – no sooner do you solve one problem than another rears its head, defying you to smack it down. When it comes to drainage, dealing with increased storm flows caused by the changing climate is a challenge all of us will have to face in the coming years. But that’s a topic for another post.