Over the years, because of my role as a consultant to the Philadelphia Water Department, I have been allowed to dig through the files in various city offices in search of items of historical interest. In particular I was given broad access to the files of the Survey and Design Bureau of the Philadelphia Streets Department. Thousands of plans that were brought to light by this work can be viewed here.

But I also found many other items in the Survey files that weren’t maps or plans and which have never published anywhere. These include reports, legal documents, photographs, pamphlets, and other ephemera. Many are one-of-a-kind, others are hard to find, and all of them (to my mind at least) are interesting and worth presenting.

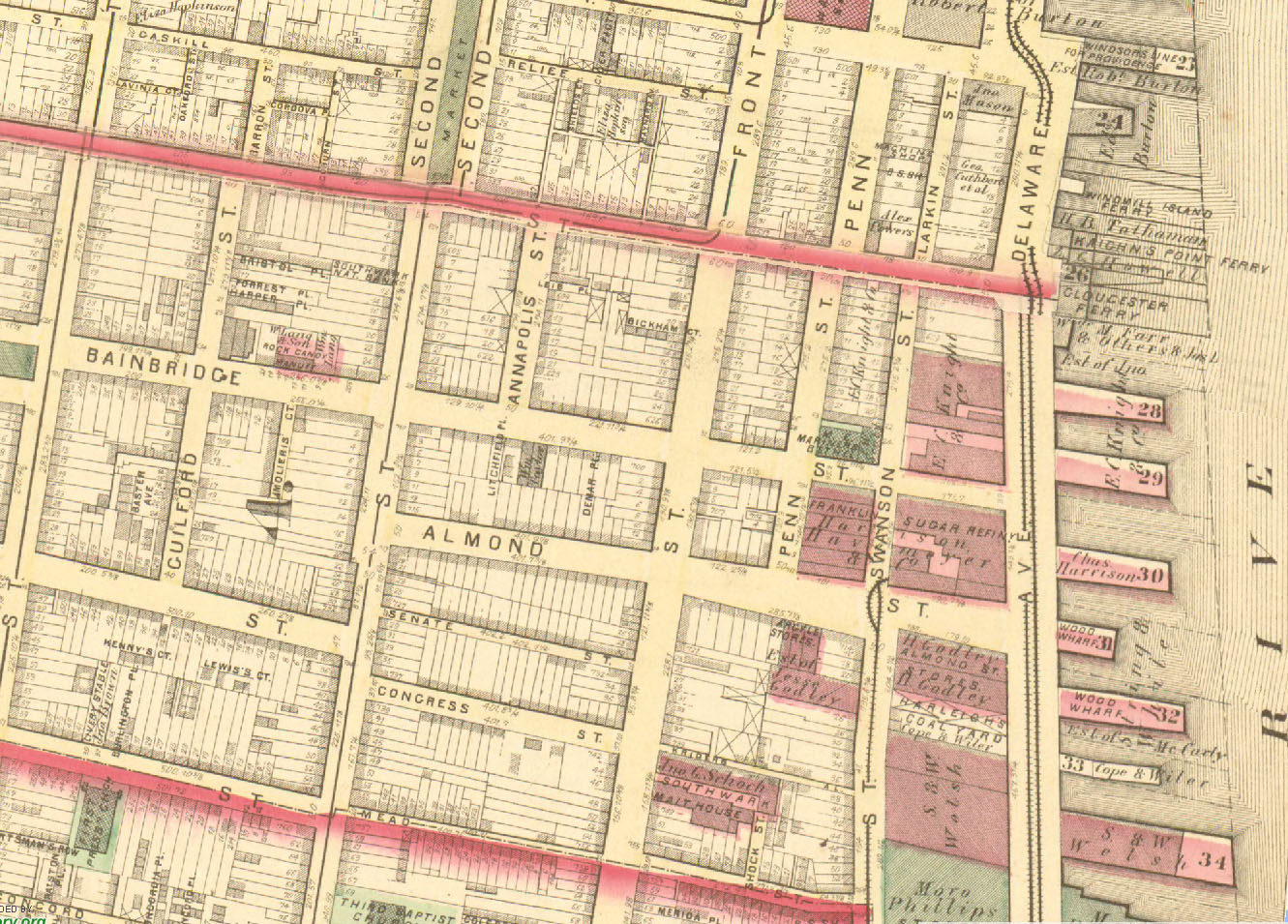

One of these is an 1887 petition to vacate a small portion of Penn Street, filed by Harrison, Frazier and Co., owners of the Franklin Sugar Refinery, located in South Philadelphia at the Delaware River between Almond and Bainbridge Streets, Vacating a street means that the city takes it off the official city plan. This is most often requested by property owners trying to expand their building footprint across street lines, but in the case of the refinery, they wanted the street dedicated solely to their use for a railroad spur for deliveries and shipments.

Of the two streets that bisected the property, Penn Street was the least significant of them, according to the petition, and used very little by the general public. Raw sugar entered and shipments of refined sugar left the complex via a railroad spur along Penn Street, and the petition stated that the company could expand its business if it had unfettered access to that right of way.

The petition was granted, and on March 4, 1887, Mayor William Smith signed an ordinance ordering the Department of Surveys “to revise the city plan so as to strike therefrom Penn street from Almond street to Bainbridge street, in the Fourth Ward.”

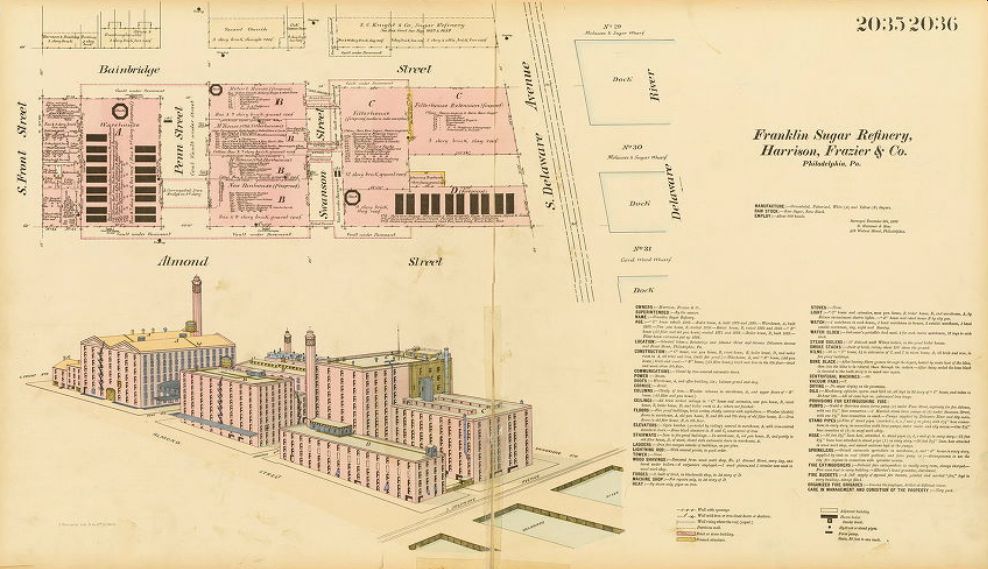

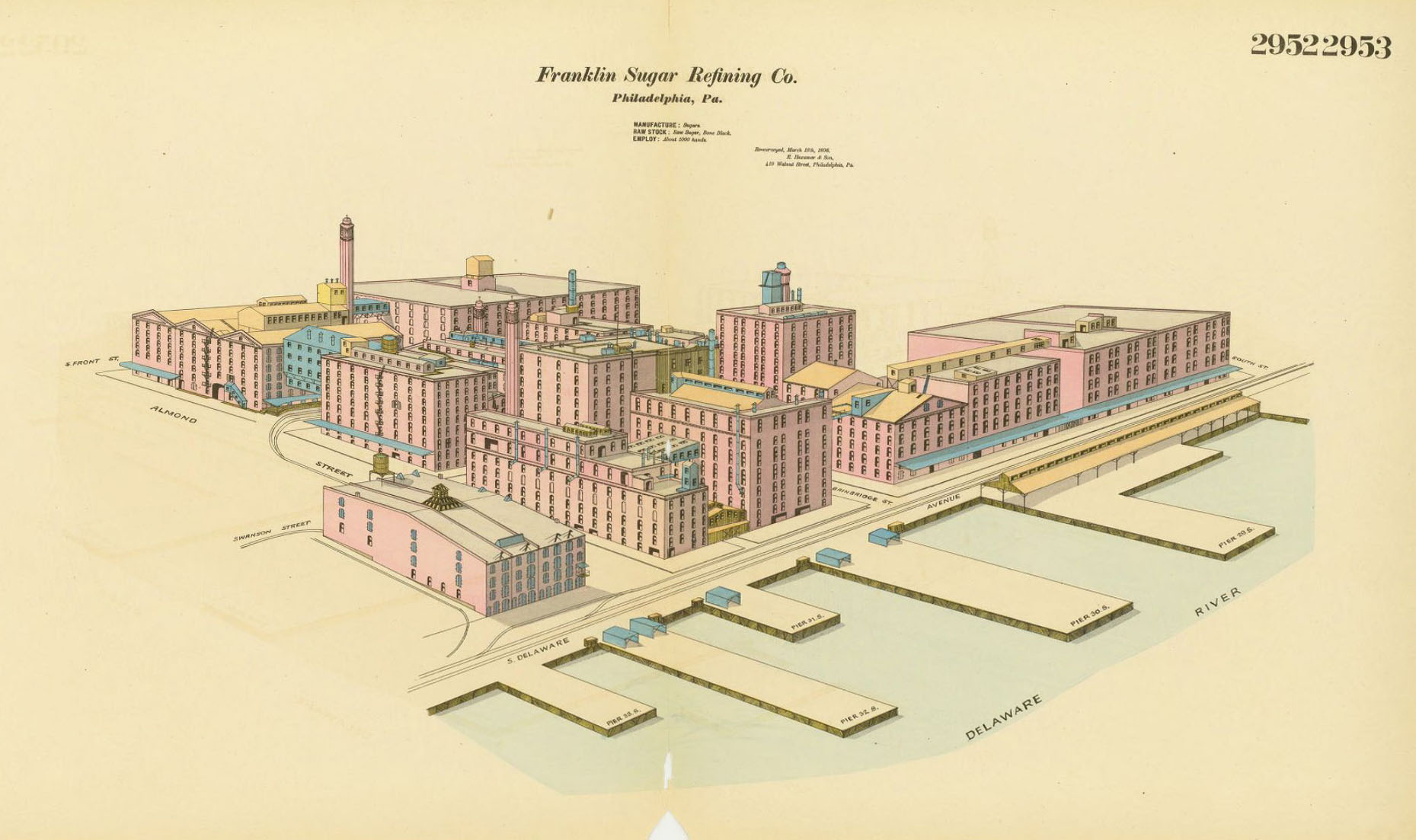

Am 1886 view of the refinery is below, showing the rail spur into Penn Street and a small elevated walkway connecting the buildings on either side of the street.

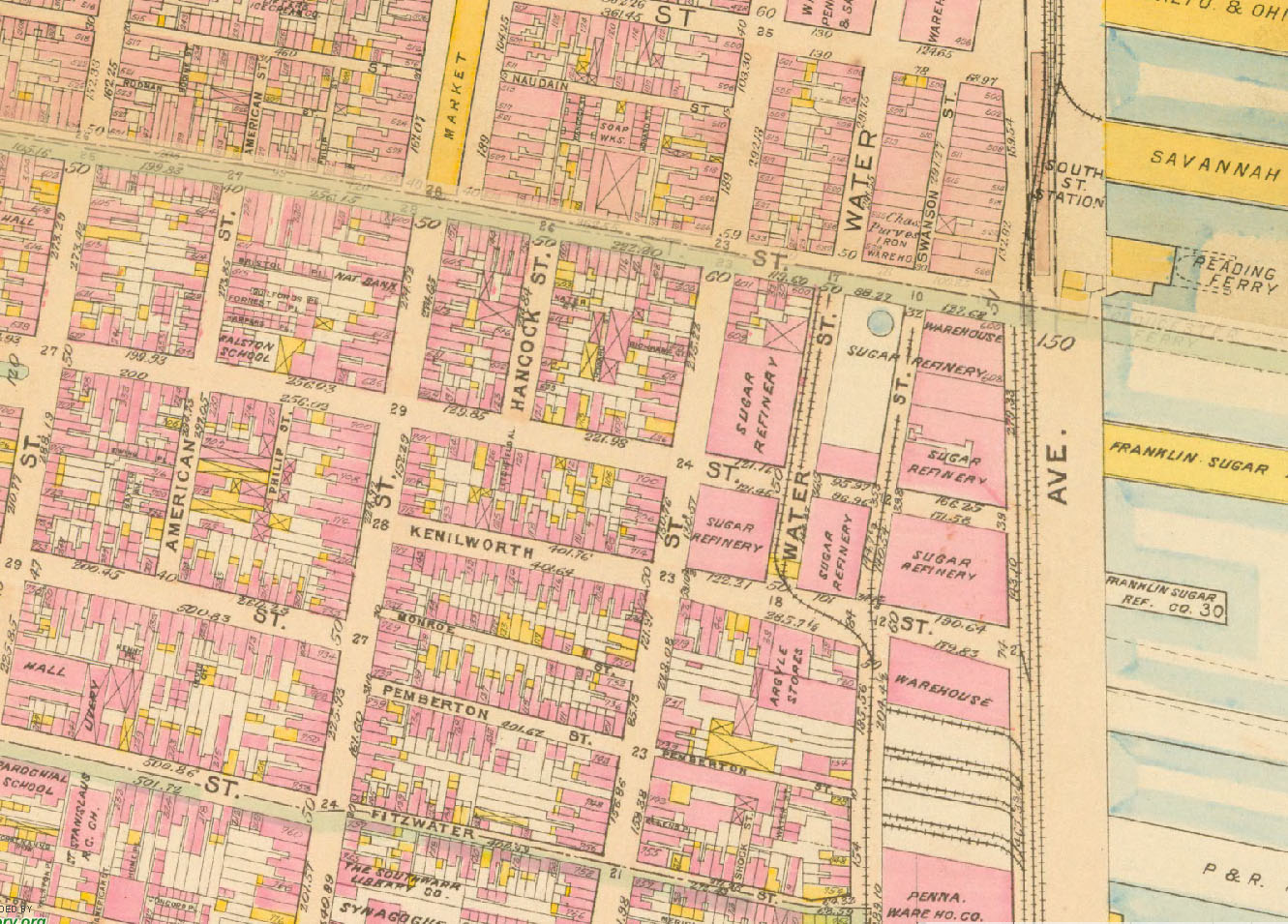

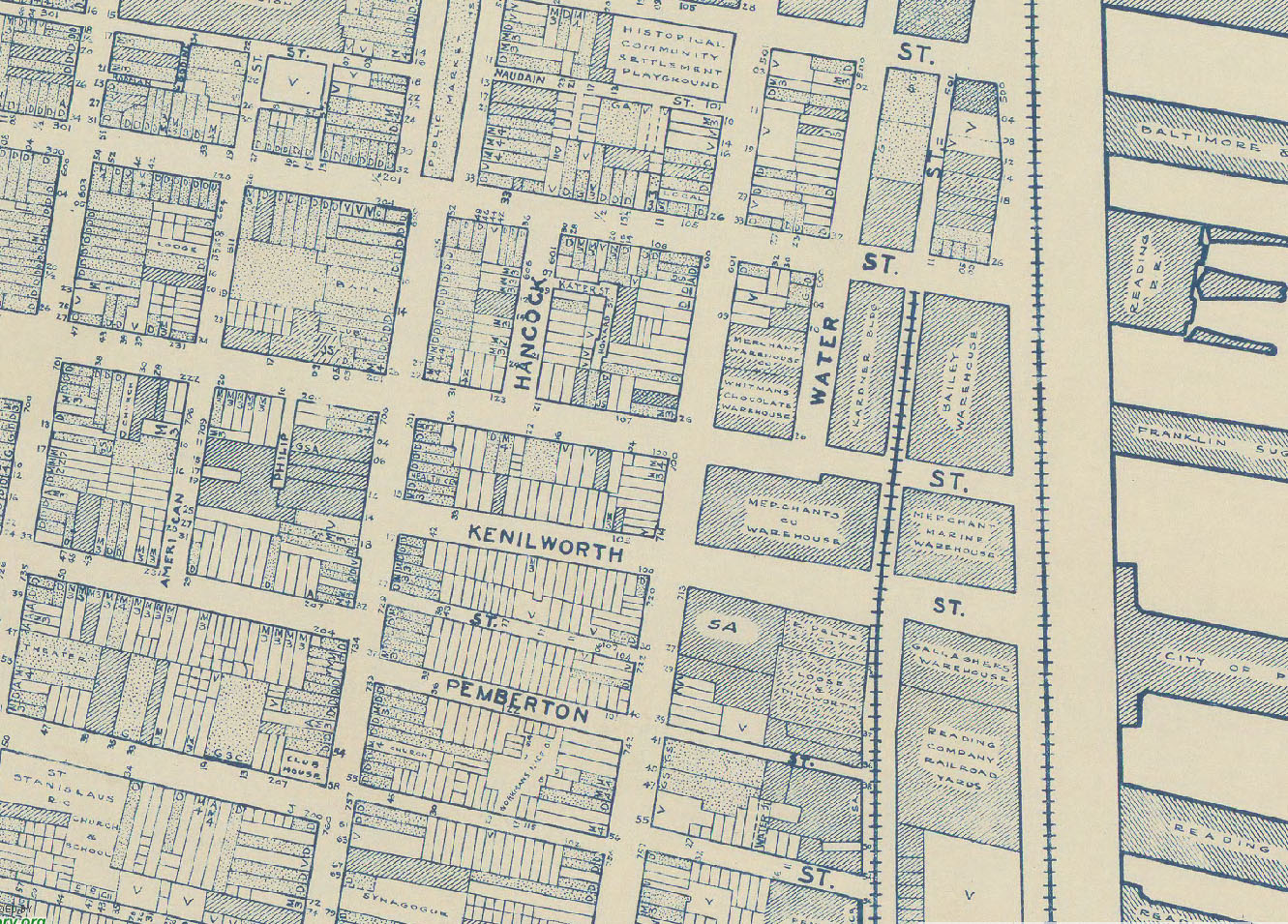

As shown on the 1896 plan below, once Penn Street was vacated, the small iron bridge over the street was increased to about five stories high, accommodating connecting bridges and “sugar bins and conveyors.” The rail facilities beneath this structure were also expanded.

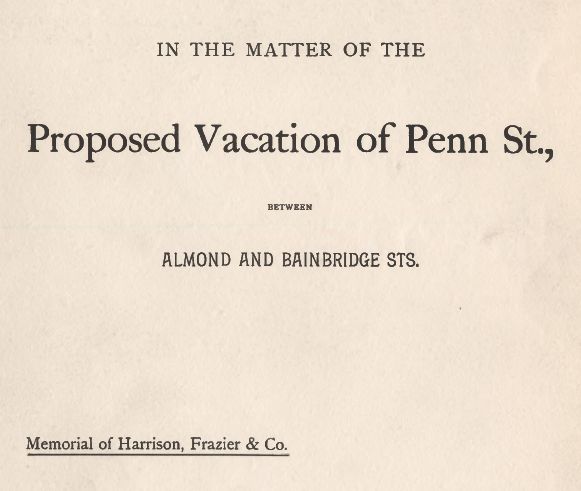

To justify the company’s bid to take over the street, the petition outlines the importance of the refinery’s role in sugar manufacturing in the United States, along with the ancillary employment the plant supported – information that, to me, is far more interesting than the simple closing of a street. Excepts from the petition, addressed to members of the city’s Select and Common Councils, are below.

Gentlemen:—We feel constrained to address you, briefly, in regard to our application to have Penn St., between Bainbridge and Almond Sts., stricken from the City plan; and in so doing we shall have to depart from our rule of conducting our business in a quiet manner, and not in any way referring to its magnitude or importance. The facts are briefly these:

We have erected within the last twenty years, by constant improvement, the finest sugar refineries in the world. They have never ceased work since 1866, when the original building was started. Our daily consumption of raw sugar is over one million pounds per day, for every day in the year, except Sundays;—equal to one cargo of raw sugar a day, and with an annual product exceeding $15,000,000 in value.

If you will for a moment consider what this means to the City of Philadelphia, from the time the vessel enters the Capes of the Delaware until she leaves it again with her outward cargo, we think you would be astonished at the importance and greatness of this industry: the tug-boats and the pilots which bring the vessel to her dock; the stevedores who unload the ship; the weigh-masters who weigh the cargo; the truckmen who haul it to the refinery; the many hundreds of workmen directly employed in the refinery; the barrel factories and the boneblack factories in this city engaged all the year round supplying it with material; the 250 tons of coal which it uses every day; the machinery made here for it; the furnishing of supplies to vessels, and the bringing of great numbers of vessels to this Port, furnishing the basis of its export trade for grain, coal, provisions, cooperage stuff, etc., etc., and the thousand and one ways in which, from the raw material to the refined article, the Philadelphia workmen contribute to this enterprise, you would find that many thousands of men are kept constantly employed in the various operations and duties connected with it. Its business pays over 25 per cent, of the total customs revenues of the Port, and brings to Philadelphia 50 per cent, more sugar than the whole State of Louisiana produces.…

The petition ends with this:

Of all the refined sugar made in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, one-eighth is manufactured by the Franklin Sugar Refineries and is delivered in this block of Penn St., between Almond and Bainbridge Sts.; thus using this street almost to its utmost capacity and in the very best way in which it can be used. When you consider that the sugar used by over six million people is delivered upon this street, which is unnecessary to any one else, and that we desire to avail ourselves of the privilege which you have granted us to lay a railroad track upon this street between our refineries, connecting with the railroad on Swanson St., we feel that further statement on our part will not be called for.

These sugar refineries represent one of the very finest plants in the world. Not only would any community, but any nation would be glad to have them within its borders. They give employment, directly and indirectly, to immense numbers of men. The extent of the interest which Philadelphia has in them can be summed up in the striking fact that more than 25 per cent, of the total customs revenues at the Port of Philadelphia is paid on the sugars used in these refineries.

To see a PDF of the entire petition, click the cover page below.

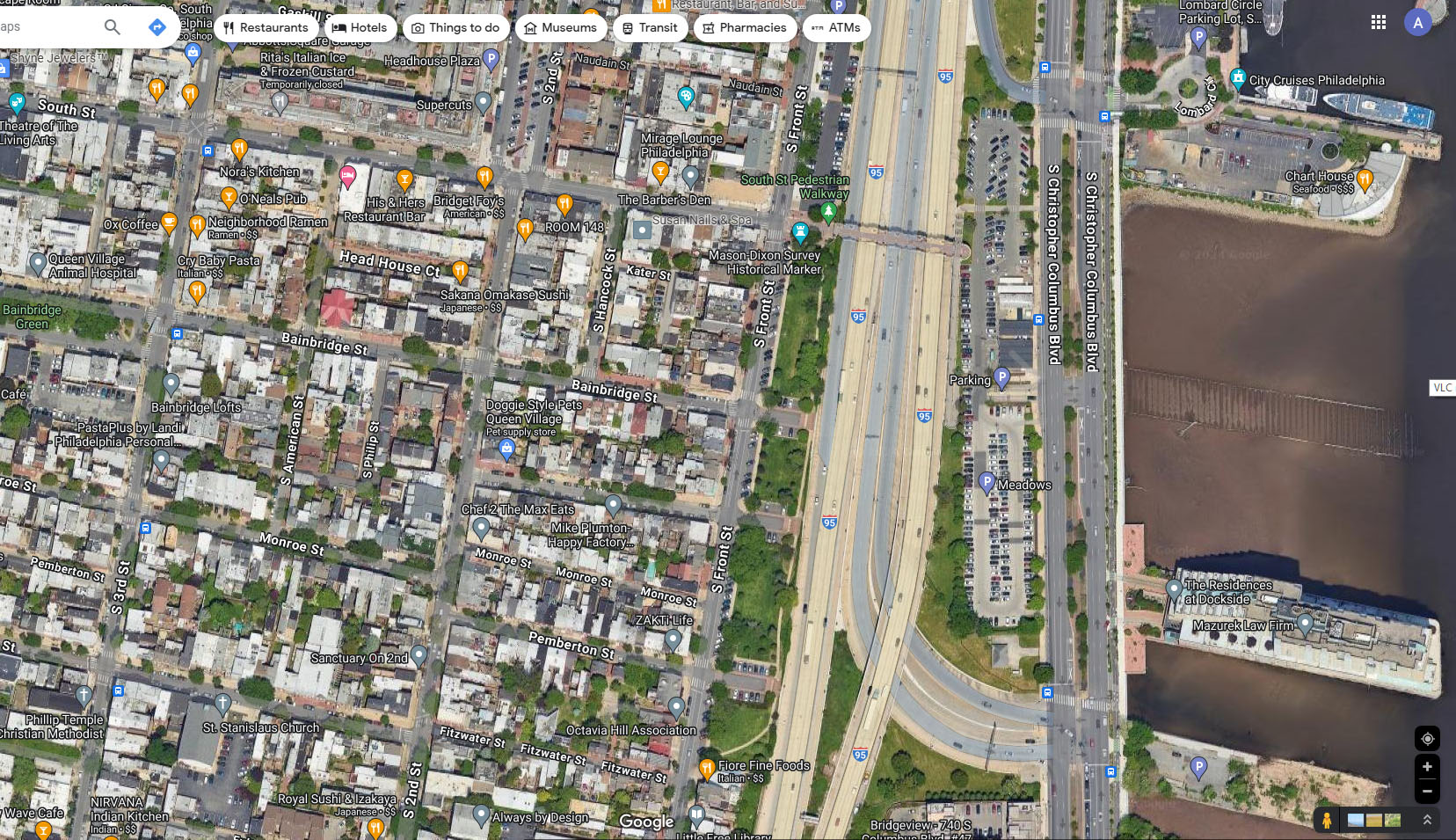

The following series of maps, created using the Greater Philadelphia Geohistory Network’s Interactive Map viewer, clearly shows the rise and demise of the sugar refineries and other industry along this section of the city’s waterfront.